Agriculture’s Talent Pool Needs to Reach Beyond Farms

TOPICS

StillFarmingGuest Author

Special Contributor to FB.org

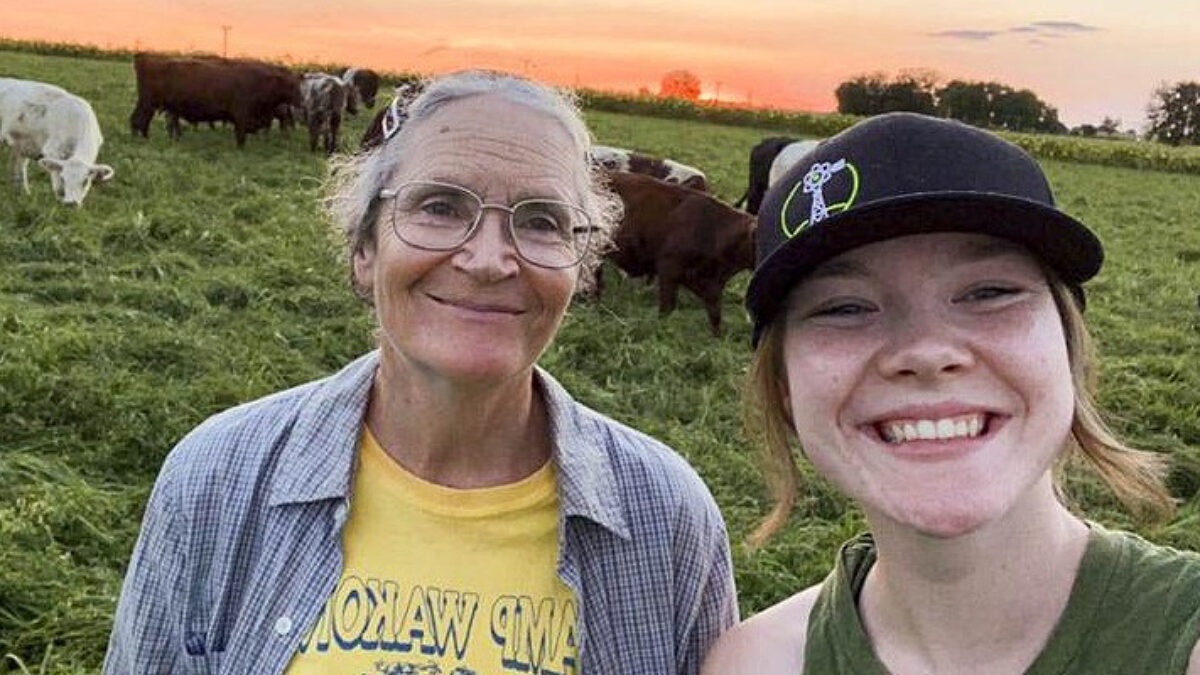

photo credit: Miriam Hoffman, Used with Permission

Guest Author

Special Contributor to FB.org

By Miriam Hoffman

My mother exemplifies the ethos of the ideal American farmer: a thoughtful steward of the land, an acute decision-maker, and a relentlessly hard worker.

Watching her work cattle is like watching Gordan Ramsay cook a gourmet dinner or Brad Paisley play an electric guitar riff.

It seems obvious she’s been doing it all her life, she’s so good at it. Except, she hasn’t.

Is agriculture so different from other fields that you can’t ever understand it without being raised by a farmer? Can we afford to exclude the talent, ideas, and perspectives of those not agriculturally minded from birth and still remain a competitive modern industry?

Is agriculture so different from other fields that you can’t ever understand it without being raised by a farmer?

I recently saw a Twitter thread which asked a question along the lines of, “Is it possible for someone not born into agriculture to understand the industry?” As an “ag kid” myself, it’s tempting to think the answer is a resounding no.

I mean, just look at all the ways agriculture is different from other industries — from being at the mercy of volatile weather, to the often generations-deep emotional attachment to land and livestock, to the fact we produce one of the necessities of life for every human being. It’s clear agriculture is cut from a different cloth.

Yet, as unique as agriculture is, I can’t help but feel we’re missing something if we only look to ourselves and our own offspring for ideas, talent and good people.

Consider my mother’s experience.

Other than the occasional elementary school field trip, my mother didn’t step foot on a farm until she was 21 and several years into college. The daughter of two doctors, she wasn’t the typical agricultural engineering student. She didn’t study agriculture because she was raised in it, wanted to continue a family tradition, or any of the reasons most of us born-and-raised farm kids continue down an agricultural career path.

She studied agriculture because she found it fascinating. She worked on a diversified crop and livestock farm in north-central Illinois for several summers to get hands-on experience and conveniently, at least for the sake of my existence, she married the farmer. Over 40 years later, she’s still farming. The last 17 years since my father’s passing, she’s continued on.

Along with several of my siblings, she’s continuing to streamline our cattle genetics business. She’s helped diversify our operation into organic grain and produce markets.

My mother is a leader in purebred dairy cattle associations, a source of sage wisdom on caring for cattle, and keenly aware of how and why agriculture is — and must continue — focusing on people.

Sure, being born into a farming family lends advantages in pursuing an agricultural career. You have a head start in understanding the unique quirks of the industry and are likely have family friends who double as members of your professional network. Yet, I believe our greatest disadvantage is a bent toward feeling superior simply because of our background. If we’re not careful, our very love for the industry of agriculture could become its downfall.

Why would we curtail the talent pool in our industry because of the notion that you have to be born an agriculturist to become one? Just because farm kids have a foot in the door already doesn’t give us an excuse to exclude those who don’t.

As the economy continues to integrate, with more overlap among sectors like agriculture, food science, financial technology and others, we must pursue relentless innovation to remain relevant.

But it’s more than just staying relevant. The best tables for developing strong ideas are those filled with people who don’t all think the same thing.

National Football League player-turned-farmer Jason Brown has cultivated his own success on a North Carolina farm in part because of his newness to agriculture, bringing his ideas to all types of industry tables at conferences across the country.

His classroom consisted of YouTube videos, a 1,000-acre farm, and a willingness to fail and try again. People like my mother and Jason bring a freshness to agriculture that people like me cannot.

Those of us “insiders” are blind to some of our own inconsistencies and weaknesses. I know I certainly take many things for granted. Individuals with a fresh perspective on agriculture, like my mother, bring awareness to our blind spots in ways those of us born into the industry simply cannot see. We can’t limit our talent and idea pool because of a misplaced belief that we’re better because we were here first.

My mother wasn’t born on a farm. She didn’t hang out with farmers when she was a kid. She didn’t simply marry a farmer. She became one.

It seems the ethos of the American farmer is less about where you were born and more about how you choose to embrace your curiosity, invest your talent, and step into the unknown. Born into it or not, these are the attitudes agriculture needs.

Miriam Hoffman, 21, is an Illinois Farm Bureau member who loves agriculture, people and learning new things about the world. She moved from the family farm in LaSalle County to Southern Illinois University Carbondale and studies agribusiness economics. This column is republished with permission.