2025 AEWR – Labor Costs Continue to Climb

Samantha Ayoub

Associate Economist

While most Americans have their sights set on Thanksgiving, farmers who use the H-2A program were focused this week on USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service’s Farm Labor report, released on Nov. 20, as it offers a glimpse into their future operational expenses.

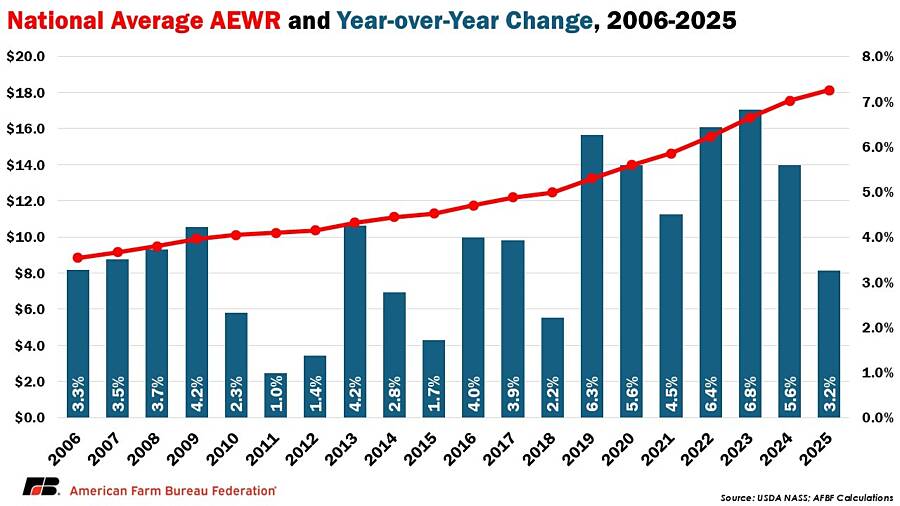

Each year, the Department of Labor (DOL) uses the “field and livestock workers’ combined” wage rate reported in the November Farm Labor report (based on the Farm Labor Survey or FLS) to establish most H-2A workers’ minimum wage, known as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR). This year, the combined field and livestock worker wage rate nationally is $18.12, up 3.2% from the 2023 release. Regional wages increased an average of 4.5%, but this reflects wide ranges of change across the country. The new wages become official when DOL publishes them in the Federal Register in December. But this wage increase isn’t the only hurdle H-2A users will have to clear in 2025.

What to Expect in 2025

The FLS collects data twice a year – every month in California – through voluntary farm surveys in every state expect Alaska. These surveys collect employment and wage data for 1 week each quarter – in January, April, July and October. The November FLS reports the annual average combined field and livestock wage for 15 regions and three states – California, Florida and Hawaii. The combined field and livestock wage in the FLS includes six Standard Occupation Classifications (SOCs) – graders and sorters; agricultural equipment operators; farmworkers: crop, nursery, and greenhouse; farmworkers: farm, ranch, and aquacultural animals; packers and packagers; and agricultural workers, all others. Over 96% of H-2A workers fall into these SOCs. The remaining employment contracts that include any job requirements outside of these SOCs, including five of the top 10 fiscal year 2024 H-2A occupations, and any Alaskan employers will update their AEWR when the respective state’s May 2024 Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics is released in early April 2025.

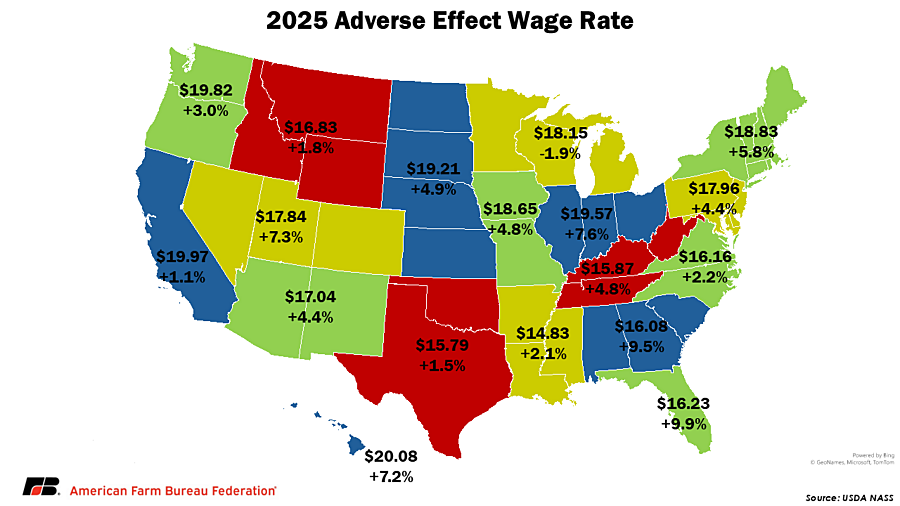

The national average combined field and livestock worker wage released in this report had the lowest growth rate since 2018, but no employers pay the national wage, as they pay the regional wage for their state. On average, AEWRs will rise 4.5% from 2024, but where an employer is located will have big impacts on their wage change. Regional wages vary substantially, ranging from $14.83 in the Delta region – Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas – to $20.08 in Hawaii.

Eleven of the 15 regions will see an increase in wages larger than the national growth rate. The Southeast – South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama – and Florida can expect a 10% increase in 2025, over $1.40 more per hour. In comparison, nonfarm wages rose only 4% from October 2023 to 2024. Florida began raising its state minimum wage $1 per hour each year in 2020 until it reaches $15 per hour in 2026 which may be contributing to spikes in farm wages.

California’s wage increased only 1% this year, a relief after averaging an increase of 7.3% each year for the last five years. After five years with the highest AEWR, California will fall to second with an hourly wage of $19.97, following only Hawaii, where farmers will be required to pay $20.08 per hour, up 7.2% from 2024. However, California is the third-largest employer of H-2A workers with 37,511 certified positions in fiscal year 2024, while Hawaii had only 251 positions certified in the same year.

Interestingly, the Lakes region – Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota – had a decrease in the combined field and livestock wage rate in 2024. It is possible that declining response rates in the Lakes region have affected the data collection. Michigan has also seen decreases in the number of H-2A employers in their state in fiscal year 2024. This may indicate that higher paying employers, including those utilizing H-2A, are exiting the program in response to rising production expenses, including labor. It is also possible that shrinking net farm incomes have reduced the ability of farmers to offer incentive pay, such as a piece rate. Since the FLS collects gross wages that include bonus compensation, a decrease in incentive pay would lead to an overall wage decrease. While the FLS results are typically copied and pasted into the new AEWR announcement, DOL has the authority to establish other wages. So, H-2A employers in the Lake region will have to wait until December to see if their minimum wage rates will follow the survey down.

Implementation Inconsistencies

The timeline to implement the new 2025 AEWR will vary depending on where the employer is located. DOL finalized a new Farmworker Protection Rule in April 2024 that, in addition to many other provisions, removed the traditional 14-day implementation period for employers to begin paying the new AEWR. Seventeen states – Georgia, Kansas, South Carolina, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia – sued DOL over the rulemaking, and as of August 26, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Georgia granted a temporary halt of the rule in the filing states. Rather than pausing implementation of the rules across the country, DOL now has different requirements for employers in just those 17 states. While 48% of H-2A workers are employed in the states who filed for an injunction, for most states, this is the first year that employers will be required to immediately begin paying the new AEWR upon certification in December. Navigating the divided DOL guidelines and having to immediately alter business operations to accommodate new wages has added to the administrative burdens of employing H-2A workers.

Conclusion

Fruit and vegetable farmers, the largest users of H-2A, spend 38% of their farm expenses on labor, and that share will continue to grow if wages grow as they have in recent years. Rising farmworker wages are a considerable challenge to American specialty crop producers competing with farmers in other countries who can hire at a fraction of the cost.

DOL’s methodology of directly using the average wage rates from the FLS as the minimum H2A wage has raised concerns among users of the program, especially since it does not account for the substantial additional costs of transportation and housing, as well as the direct and indirect administrative costs of using the program.

Nevertheless, H-2A workers have become vital to American food production as the domestic workforce continues to move away from agricultural labor.