2025 Tax Cliff: Individual Income Provisions

TOPICS

Tax Reform

Samantha Ayoub

Economist

The Dec. 31, 2025, expiration of many provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) adds a new task to the 2025 congressional to-do list: updating the tax code. Many TCJA provisions provided important relief for farm families. While reductions in the corporate income tax rates were made permanent in 2017, income tax cuts for individuals began to phase out in 2022, with the biggest tax increases coming with expirations at the end of 2025. This Market Intel report is the fourth in a series exploring the expiring TCJA provisions – including individual tax provisions, the qualified business income deduction, capital expensing provisions and estate taxes – and their impact on farm families.

The majority of farm profit nationwide is taxed as a farmer’s or rancher’s individual income, so changes to the individual tax code significantly impact farm tax liabilities. Farmers utilize business provisions like bonus depreciation, full depreciation, business income deductions and alternative use valuations to reduce their tax liabilities from farm profit, but the individual income tax code is the ultimate determination of most farmers’ yearly tax burden.

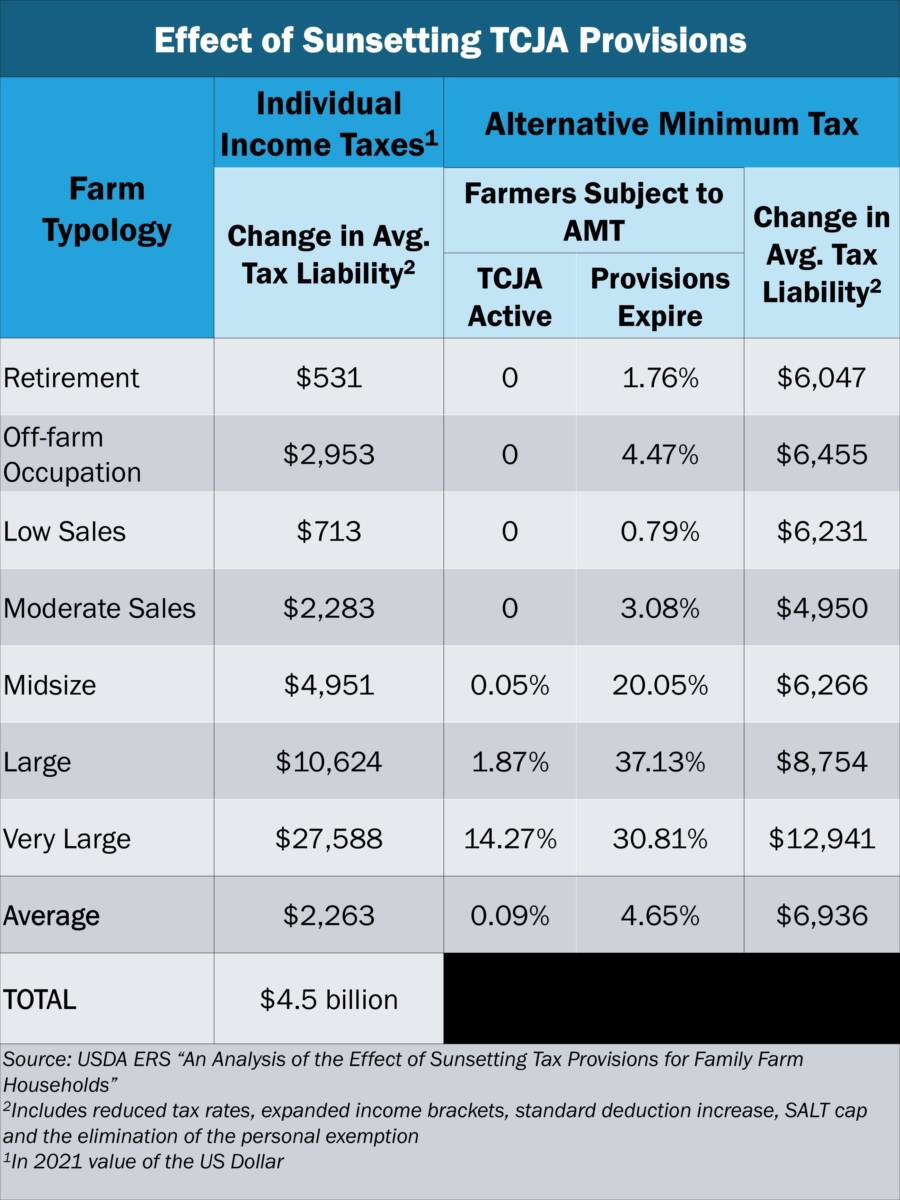

TCJA individual income provisions that reduced the average farm tax liability across farms of all sizes include reduced federal income tax rates, new income ranges for each rate, increased limits for the alternative minimum tax (AMT) and limits on personal deductions. Combined, these provisions have the single largest impact on farmers and ranchers’ tax liability. Were they to expire, USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) estimates the average farmer would owe an additional $2,300 a year in taxes, not including any other expiring provisions. These expirations alone increase farm taxes paid by $4.5 billion.

Farm Businesses

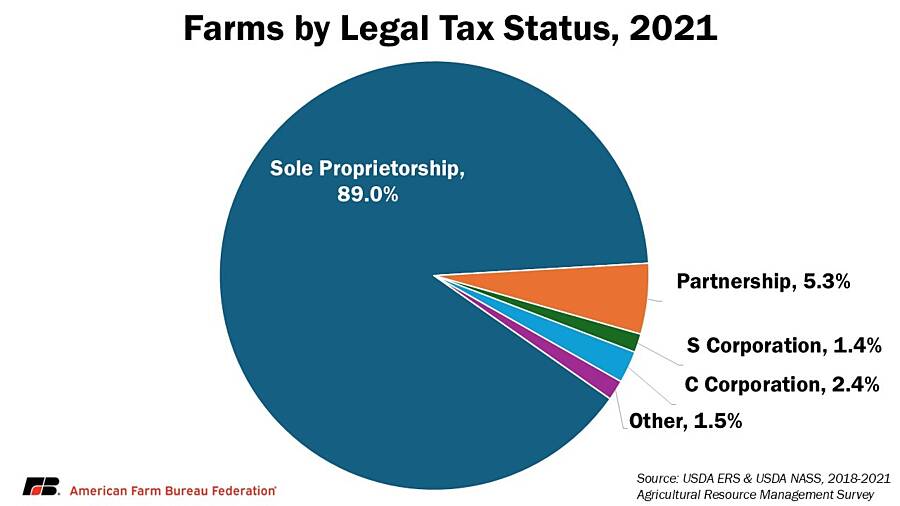

Nearly 98% of farm operations are pass-through entities: sole proprietorships (which are not legally separate from the operator), S corporations and partnerships. While C corporations, including co-operatives, are taxed at a corporate tax rate on their business income and then taxed again as individual income when dividends are paid out to stakeholders, pass-through entities include business profit in its entirety as personal income.

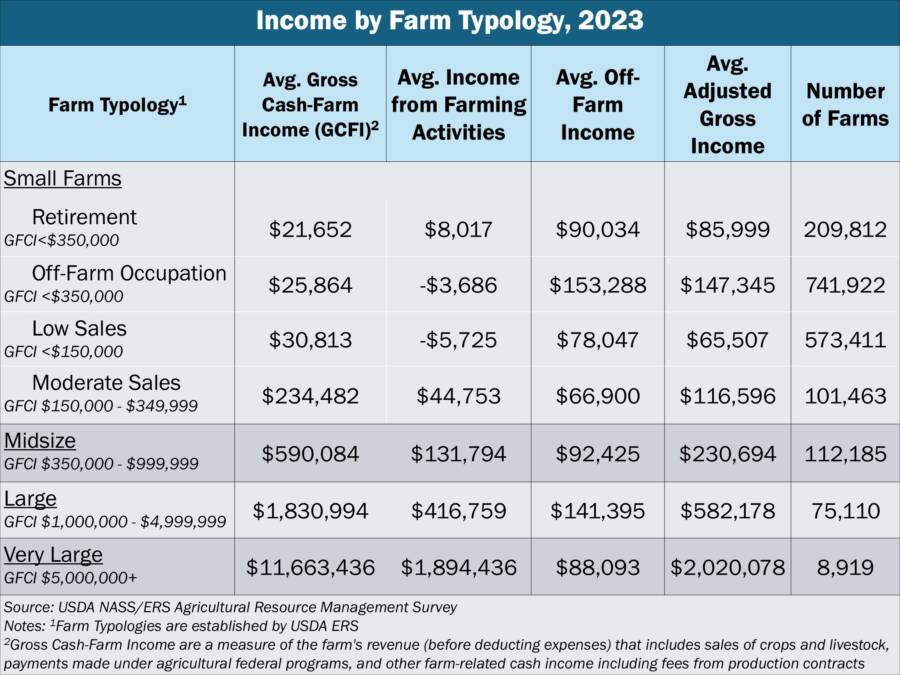

In pass-through businesses like farms and ranches, all sources of income combined determine what individual income tax brackets the owner’s income will fall into – and thus how much they will pay in taxes. Ninety-six percent of farm households receive some amount of income from off-farm employment. In fact, 85% of farm households earned the majority of their income off-farm in 2023. Midsize, large and very large farm families are the only categories that earn the majority of their income from farming, and even those have a large share of income coming from off-farm jobs, on average.

Adjusted gross income (AGI) is the total income, from all sources, minus deductions or exemptions, for the household. Only farm profit is counted as income, not total revenues. Farm losses can also be carried back to the two preceding tax years or forward to a later year; farming receives this carryover because of the extreme year-to-year volatility of net farm income. AGI is the ultimate amount of money that a farmer will pay taxes on at the designated rates. TCJA made vital changes to what is deducted to determine AGI and changed the tax liability across all income levels.

TCJA Income Taxes

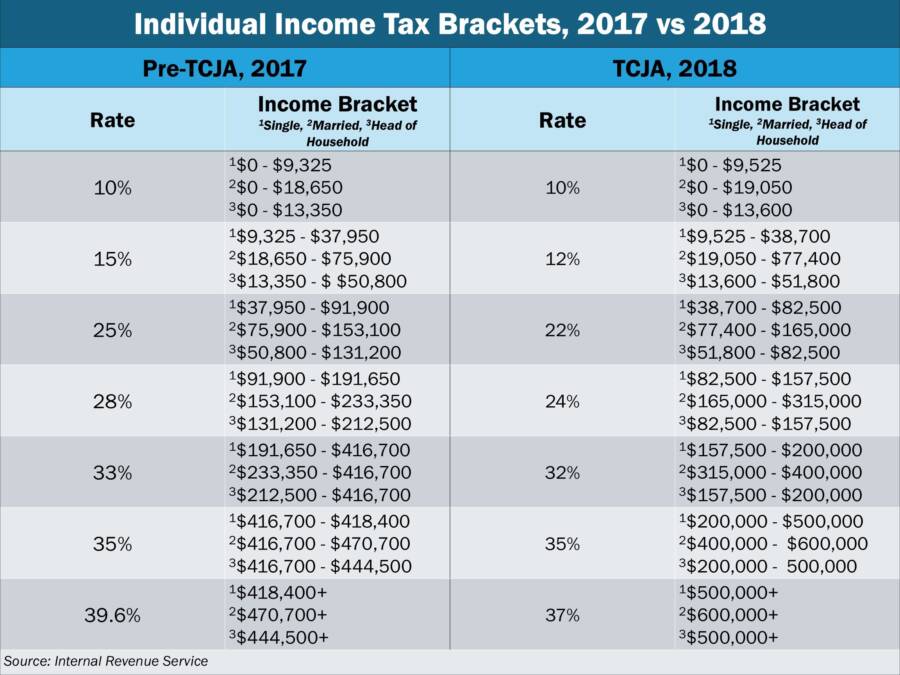

TCJA reduced individual income taxes through a twofold approach: lower tax rates and new income brackets for each rate. These changes accounted for over 70% of the TCJA’s entire tax savings. The average taxpayer saved $1,260 from the individual rate changes, increasing after-tax income by nearly 2%.

In our marginal tax-rate system, a taxpayer does not pay one rate on all their income, but rather the total bracket liability immediately before their income amount and a portion of their top income in the maximum rate. For example, a moderate-size farm filing a married, joint tax return with an adjusted gross income of $117,000 would pay $18,000 in taxes in one year: 12% of $77,400 ($9,288) plus an additional 22% on the $39,600 above the threshold for the 22% tax bracket. Before TCJA, that same farm would have paid $21,660 in taxes. TCJA’s changes to the individual tax rates and brackets lower the overall effective rate – the percentage of income paid toward taxes – of individuals. In this example, the farmer dropped from an effective rate of 18.5% in 2017 to 15% in 2018.

Changes to Deductions

The TCJA aimed to simplify tax filing by reducing the amount of itemized deductions a tax filer is eligible to make. First, the $4,050 per household member personal exemption was completely repealed. To offset this loss, the standard deduction – the set amount any income-earning taxpayer may reduce from their taxable income at once instead of itemized deductions for each eligible expense – was increased: from $6,350 in 2017 to $12,000 for single taxpayers in 2018; $12,700 in 2017 to $24,000 in 2018 for married taxpayers filing jointly; and $9,350 to $18,000 in 2018 for heads of households. Families with dependent children under 17 years of age also receive $2,000 per qualifying child, double the child tax credit from before the passing of TCJA. The child tax credit also reaches more families under TCJA by raising the phaseout threshold to $200,000 of AGI for single parents or $400,000 for married couples from $75,000 or $110,000 for single or married taxpayers, respectively, in 2017.

Another deduction restriction that was used to offset lower TCJA tax rates is a cap on state and local taxes (SALT) deductions, particularly income, property or sales taxes. SALT deductions aim to reduce federal tax liability by balancing income already spent on taxes for local services. Prior to TCJA, there was no limitation on how much of these local taxes a taxpayer could deduct; TCJA implemented a $10,000 maximum SALT deduction. In 2017, 30% of tax returns included some amount of SALT deduction, but the cap decreased the share of returns utilizing SALT deductions to only 9% of tax filers nationwide by 2022. In both cases – with or without a cap – SALT deductions are disproportionately utilized by high-income earners in states with high tax rates. Nearly 65% of SALT deductions are claimed by those with incomes over $500,000 and are concentrated in California, New York, New Jersey and Illinois. USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) estimates that 3.3% of all farmers have state and local taxes greater than $10,000. However, that share increases to 23% and 43% of large and very large farm households, respectively; these are the farm families whose income depends largely on the farm business but also typically have the highest tax bill.

SALT deduction caps are only applied to individual income filings, not corporate filings. To provide relief to pass-through entities like farms that were not able to capitalize on uncapped business SALT deductions, 36 states created laws allowing pass-through businesses to pay state and local taxes at the entity level. These workarounds allow farmers to designate their SALT liabilities as specific business expenses separate from their individual tax expenses, allowing them to deduct their business taxes beyond the $10,000 cap. Repeal of the SALT deduction cap is estimated to decrease the liability of those with farms with state and local tax expenses above the cap by more than $5,900, saving an additional 3.3% of taxes from this provision alone.

Impact on Farm Tax Liabilities

The expiration of individual tax provisions in 2026 is estimated to increase the average farm’s tax liability by nearly $2,300 a year, close to 12% higher than under TCJA tax provisions, according to USDA ERS. While very large farms have the highest dollar value increase in tax liability with over $27,500 in additional taxes a year, lower earning farms are hit hardest in terms of their percentage increase in tax burdens. The $27,000 increase for very large farms is 5% higher than under TCJA. Off-farm occupation, low-sales and moderate-sales farms – more than 1.4 million farm families nationwide – would have tax liabilities increase by more than 10%. Moderate-sales farms are the lowest revenue farm category whose principal operator’s primary job is to farm and which make positive income farming, on average; these would have their tax liabilities increase by over 15% ($2,300 annually), the highest share of any farm category. Altogether, the expiration of TCJA’s individual income provisions, including lowered tax rates, increased standard deduction, a SALT deduction cap and elimination of the personal exemption, are expected to increase tax liabilities paid by all American farm families by $4.5 billion, according to ERS.

Alternative Minimum Taxes

High-income households are also potentially subject to additional taxation through the alternative minimum tax (AMT). This system replaces AGI with alternative minimum taxable income (AMTI), defined as income without certain deductions, including SALT, standard, depreciation, net operating loss and other deductions and is taxed at special rates. Families and individuals pay AMT if their AMTI tax liability is higher than their regular individual income tax calculation. TCJA made several changes to the AMT system that reduced both the number of people subject to AMT and their resulting AMT liabilities.

First, TCJA raised the amount of income exempt from the AMT from $55,400 for singles and $86,200 for married couples in 2017 to $70,300 for singles and $109,400 for married joint filers in 2018. More individuals are also eligible to utilize these exemptions as TCJA raised the phaseout threshold for these exemptions. Exemptions are phased out at 25 cents per dollar of income over $500,000 and $1,000,000 for single and married filers, respectively, compared to the original phaseout threshold of $95,750 for singles and $191,500 for married couples. These values are all indexed for inflation each year. TCJA did not change the brackets for AMT. AMTI below $220,700 in 2023 is taxed at 26% while anything above that income is taxed at 28%. Individuals must pay the higher tax burden of either their individual tax return or the AMT.

The changes to AMT reduced the number of individuals liable for an alternative tax burden. Three percent of taxpayers paid AMT in 2017, which dropped to only one hundredth of a percent in 2022. A slightly higher share of farmers pays AMT taxes than compared to the general public. If the TCJA adjustments to AMTI calculations were to expire in 2026, ERS estimates that the share of farm families liable for AMT would increase from 0.1% to over 4.5%. This would result in an increase of nearly $7,000 in tax liability on average, more than 8% higher than under TCJA, for farm families that pay alternative minimum taxes.

Conclusion

With more than 96% of farms passing business profits directly through to their individual income, provisions in the individual tax code play a huge role in determining the tax burden on farm families. Increased taxes would add to farmers’ current difficulties, as farmers continue to face increasing production expenses and declining farm profits. Decisions made this year about the TCJA’s individual income provisions will have implications for farmers’ and ranchers’ real profitability for years to come. Farm profits have decreased 23% since 2022, driven by a combination of lower crop revenues and higher production expenses. With everyday farm production expenses up 6% in two years, including a 10% increase in taxes and fees, added tax burdens could weaken a farm economy that is already struggling.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL