Agricultural Land: To Own or To Rent?

TOPICS

Ag Land

Samantha Ayoub

Economist

In 2022, 39% of agricultural land was rented – a proportion that has remained relatively stable for over 50 years. When deciding how to acquire land, rising farm real estate values can be a valuable asset or an extra hit to growing production expenses. Farmers and ranchers who operate a mix of owned and rented land make up over half of agricultural land in production and are affected by both sides of land value spikes.

Land Tenure

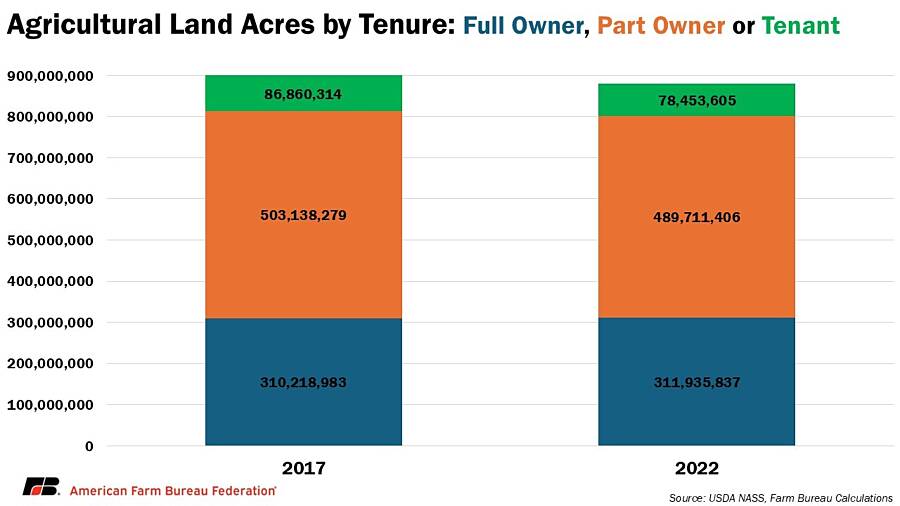

USDA has three different classifications for land “tenure”: Full owners who only operate land that they own outright; Part owners who operate a mixture of owned and rented land; and tenants who exclusively rent their land. According to USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture, there are over 880 million acres of agricultural land – comprising all cropland, rangeland and forestry land – in the United States, down more than 15 million acres from 2017. Full owners operate nearly 312 million acres of ag land, and this was the only tenure classification that increased from 2017 to 2022 despite the decreases in overall ag land acres. Still, 52% of ag land is operated by part owners, and less than 10% of ag land is operated by someone who exclusively rents land. Overall, this amounts to 39% of all acres being leased.

Twenty-eight percent of farms operate partly or entirely on rented land. These operations are generally larger than fully owned operations, with a national average size of 1,155 acres and 655 acres for part owners and tenants, respectively, compared to a full owner’s average 230 acres. As we continue to lose farming operations, the size of farms of each tenure type continues to grow through consolidation. The average part owner farm grew 13% between 2017 and 2022, more than double the growth rate of full owner or tenant operations.

Factors Driving Variation in Land Ownership

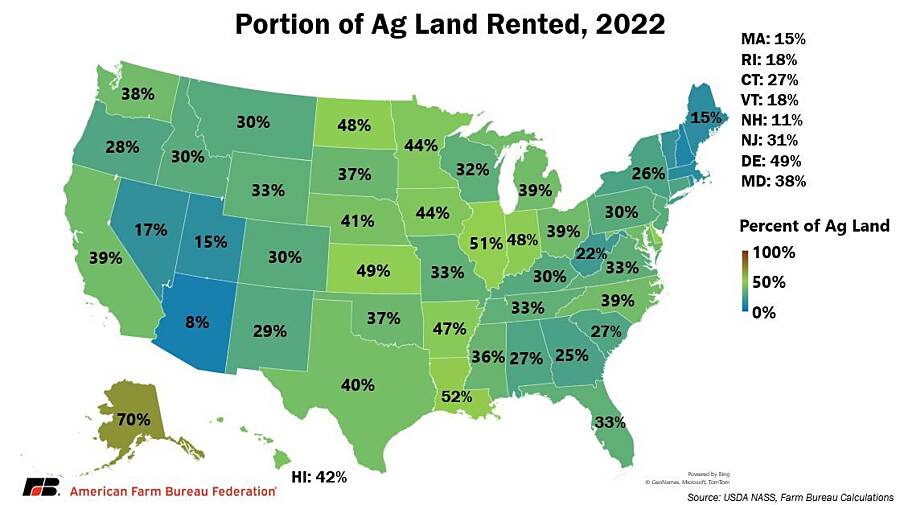

Land ownership varies between state and crop type. Most of the ag land in the Southwest and Northeast are owner-operated while operating rented land is more prevalent in the Great Plains and Midwest. In arid Arizona, Nevada and Utah, 73% of all cropland is irrigated. Cash rents for irrigated cropland are on average $100 more than for non-irrigated. Arizona, which also has high-value specialty crops, has the highest cropland cash rent and subsequently the largest share of owner-operated acres: 92% of acres are operated by owners, of which 88% of farmers and ranchers operate exclusively on owned land. New England states experience rising farm real estate values as urban development competes for land, which leads to a reduction in rented agricultural land.

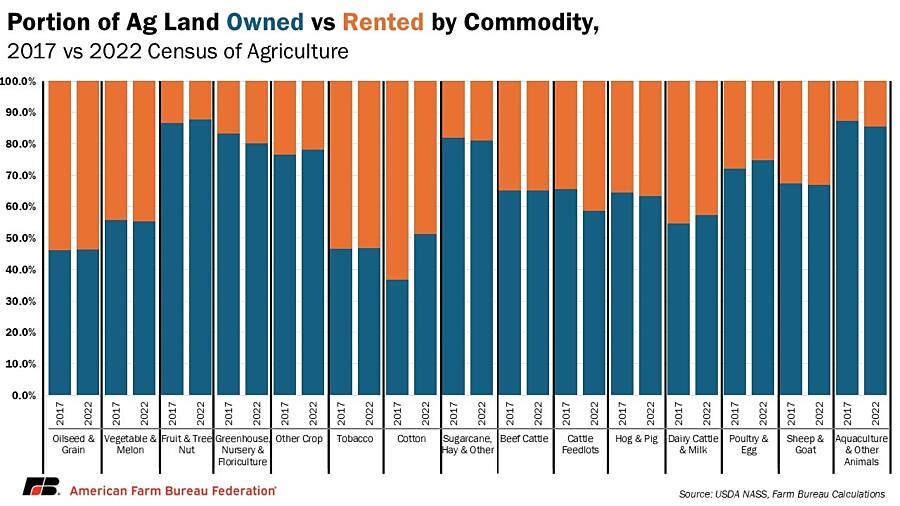

Row crops – oilseed and grain, tobacco and cotton – are the only crops primarily produced on rented acres. These crops can be easily rotated and do not require long-term changes to their fields, making it easier for renters to alter the land to their management system and for landlords to recover the land at the end of a lease. In both 2017 and 2022, 53% of oilseed and grain crops and tobacco harvested acres were rented. Cotton had the highest rates of rental production in 2017 with 63% of harvested acres rented. After extreme heat and drought in Texas reduced harvested cotton acres in 2022, only 49% of harvested cotton acres were rented. When crop conditions are poor, renters are more likely to suspend their production as they face additional expenses to operate those fields while also facing revenue losses.

When production requires significant investments – such as specialized structures or long-producing plants – farms are more likely to be operated by the owner. Fruit and tree nuts, sugarcane and hay and aquaculture or other animals have the highest proportion of owner operators with 88%, 81% and 86% of land owned, respectively. Orchards generally take many years after planting to begin producing but can continue to produce for years or even decades. Choosing to produce these crops is a long-term investment, so renting land may not lead to efficient returns over the entire production horizon. Extra investments might also come in the form of specialized equipment where a complex system – such as in aquaculture – is installed and does not easily transfer from lessee to lessor at the end of the contract.

Things to Consider

As agricultural land values continue to rise, the decision to operate owned versus rented land becomes even more crucial. Farms need enough working capital to sustain day-to-day operations. With cash receipts declining across the ag economy, increased real estate values can be used to support financing for operating loans – but only for owners. An important consideration is that increases in land value have slowed, but overall farm debt continues to rise. So, while land values might be a short-term aid to providing capital during rough years, there is no guarantee that they will grow long enough to sustain prolonged borrowing. For farms operating on rented land, high rental rates simply add to the need for operating capital and increase farm debtif the land’s return doesn’t cover the expense. Cash rents rise and fall with land values but with some lag, so when land prices rise with high crop returns, farmers can face higher rents even after returns have declined –exacerbating a poor bottom line.

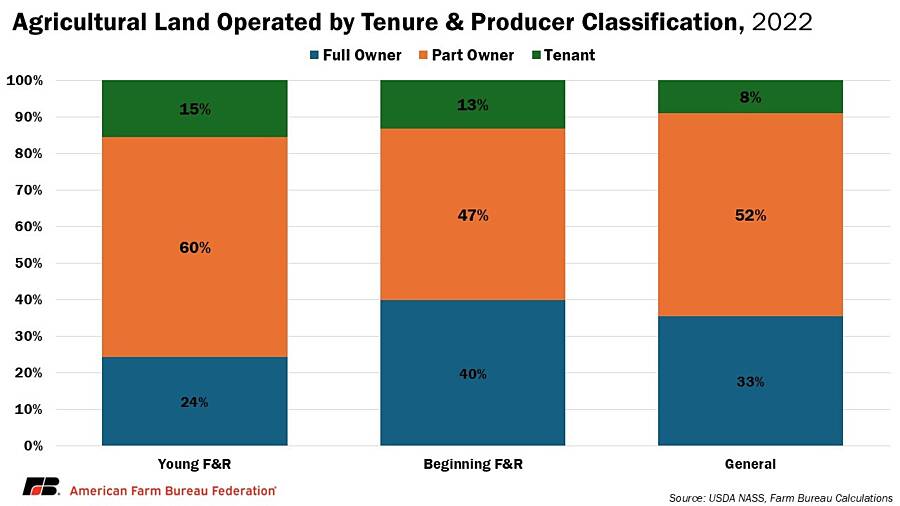

As land prices continue to rise, land attainment is one of the most significant barriers to entry for a new generation of farmers and ranchers. Young farmers and ranchers, ages 35 and under, are naturally more likely to rent land than other producers. Less than a quarter of young farmers and ranchers outright owned all the land they operated on in 2022, and they’re almost twice as likely to exclusively rent land. Only half of all farm families have succession plans on how to transition the farm from one generation to the next. For young farmers that come from farm families, renting may be the first step to operating their own portion of farmland or ranchland. As they grow in their management, they can take on more responsibilities on the family land, becoming the principal operator on a larger mix of owned and rented acres. Succession plans are a critical tool for accomplishing this transfer of management in a way that benefits both generations.

On the other hand, beginning farmers and ranchers – those with less than 11 years of experience on any farming operation – are more likely than the general population to operate only owned land: 40% of beginning farmers are full owners. The average age of beginning farmers and ranchers is 47 years old. This group on average began farming later in life, so they likely had more capital and financing options to purchase land outright to begin their operation. Beginning farmers and ranchers are still more likely than the general producer to be a tenant, though.

There may also be dueling claims for USDA program payments, particularly payouts from Title I programsbased on base acre enrollment. Despite 80% of rented farmland being owned by non-farmer landlords, receiving payment for the use of their land as a farming operation gives the landlord eligibility to receive USDA program payments. Farmers and ranchers that pay to rent that same land are also eligible to receive payments if they contribute “a significant contribution of active personal labor” or “make a significant contribution of both active personal management and equipment to the farming operation.” As renters generally oversee the production on their leased land, including making all financial investments and facing the risk of production losses, they receive preference for Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) or Price Loss Coverage (PLC) payouts in down years. This may differ if the land is leased on a crop-share basis where the revenue from a year’s production is split between the landlord and lessor. In this case, payments for losses might be split between the parties, but it largely depends on private negotiations, so it can be important for a tenant farmer that the lease clarify claims to USDA benefits.

Conclusion

As we closely follow the recent dreary outlook for farm finances, land tenure is one crucial piece that can aid or harm farmers and ranchers. Increases to land competition from solar development, urban sprawl and conservation land retirement, as well as long-term prospects for farming, may drive farmland values up in many places, even as short-term farm returns decline. This raises costs for rented farm operations but gives owners an increasingly valuable asset. The share of agricultural land that is rented has remained around 40% for decades despite farm closures and consolidations, and through other down ag economies.

The viability of farms and ranches through these worrying trends can depend on an efficient farm safety net during rough years. Yet, farm ownership can have complicated impacts on federal program eligibility. Navigating farm ownership and rental decisions requires careful management and consideration of all these factors to ensure long-term sustainability.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL