Bananas, Beverages and Bottlenecks: Second Port Strike on Deck

Daniel Munch

Economist

Everyone loves a sequel — don’t they? Well, ready or not, we’re gearing up for a second showdown between the International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA) union and the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX). A three-day strike last fall (Oct. 1-3) delivered a tentative agreement for a 62% base wage increase for hourly dockworkers (from $39 to $63 per hour) over six years, as well as an extension of the master contract to allow more time for final negotiations. However, with that extension set to expire on Jan. 15, the union could reignite tensions by calling a new work stoppage, potentially disrupting most non-bulk shipping at U.S. East Coast and Gulf ports once again.

While the broader impacts on U.S. agricultural trade align with our previous analysis, Port Strike Could Sink Access to Foreign Markets, this sequel digs deeper. We’ll explore the food and beverages consumers should keep an eye on and delve into the contentious topic of automation, a sticking point that not only divides dockworkers and employers but also affects farmers’ efficient access to foreign markets.

A Short Refresher

According to USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service, in 2023, over 70% of U.S. agricultural export value and 56% of import value relied on ocean ports. An ILA strike would primarily disrupt containerized agricultural trade, which nationally accounts for 73% of waterborne imports and just over 30% of export volume. ILA ports handle 72% of agricultural containerized imports and 46% of agricultural containerized exports, putting approximately $1.4 billion in weekly agricultural trade — $318 million in exports and $1.1 billion in imports — at risk of disruption.

Consumer Favorites at Stake

The impact of an ILA port strike will largely depend on its duration. The previous three-day strike left some lingering congestion at East Coast ports, but overall impacts were relatively muted. For consumers, shortages in grocery stores would most likely affect products that are predominantly imported, with severity increasing based on perishability and the availability of domestic supply or substitutes.

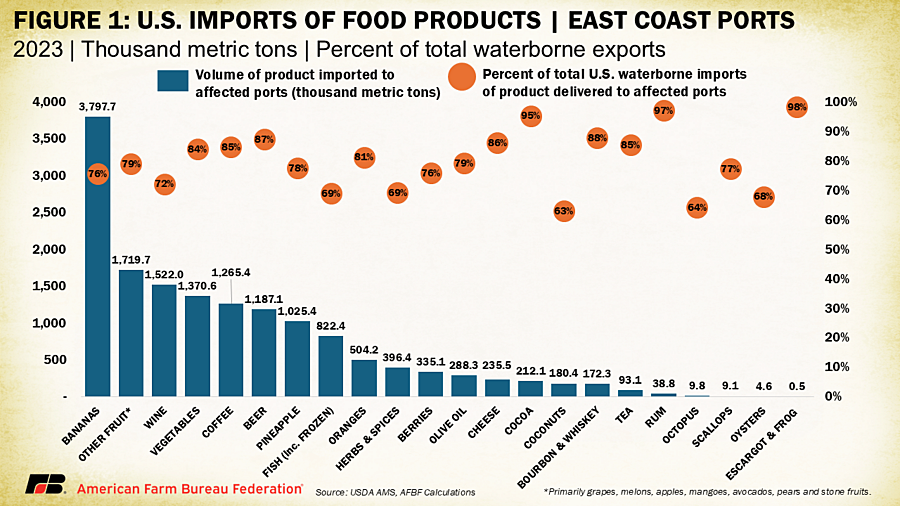

Take wine, for instance: approximately 25-33% of wine consumed in the U.S. is imported, with 72% of those imports arriving through ILA-staffed ports. While Italian-wine lovers might notice some disruptions during a strike, wine’s long shelf life means suppliers have likely stockpiled inventory to weather short-term issues. A similar story applies to beer — 18% of which is imported, with 87% of those imports entering through ILA-staffed ports — and distilled spirits, with 88% of imported whiskey and 97% of imported rum coming through ILA-staffed ports. Consumers, however, can support the many excellent domestic options for wine, beer and spirits, which not only remain readily available but also play a vital role in supporting U.S. farmers and local economies.

The stakes rise with more perishable goods. A significant portion of seafood consumed in the U.S., 70%-85%,is imported – with 69% of imported fish, 64% of octopus, 77% of scallops and 68% of oysters coming though ILA-staffed ports. While frozen seafood can last for months and may help buffer against short-term disruptions, fresh seafood is a different story. Without timely deliveries, retailers and restaurants could face supply shortages, driving up prices and leaving consumers with limited options. Air freight does handle some fresh seafood shipments but in smaller quantities and at a much higher cost.

Before we go bananas in the next section, take a moment to check out Figure 1, which highlights key food products by the percentage and volume of their waterborne imports through ILA-staffed ports in 2023. For instance, 95% of cocoa (including beans) and 85% of coffee — both products that are nearly entirely imported — entered the U.S. through ILA-staffed ports.

Did I say Bananas?

The perishability factor becomes even more critical with products like fresh fruits and vegetables. The percentage of fresh fruit consumed in the U.S. that was imported reached 48.2% in 2022 (44% excluding bananas), with the majority of avocadoes, pineapples, kiwis, mangoes, dragon fruit and papayas being sourced internationally. Bananas, as a staple of the American diet, naturally drew significant attention during the October ILA port strike. Consistently topping the list of fresh fruits in the United States, bananas have a per capita availability of 26.9 pounds annually. Their highly perishable nature means that any disruption in supply can quickly result in a lack of fresh bananas once existing stocks are consumed or spoil.

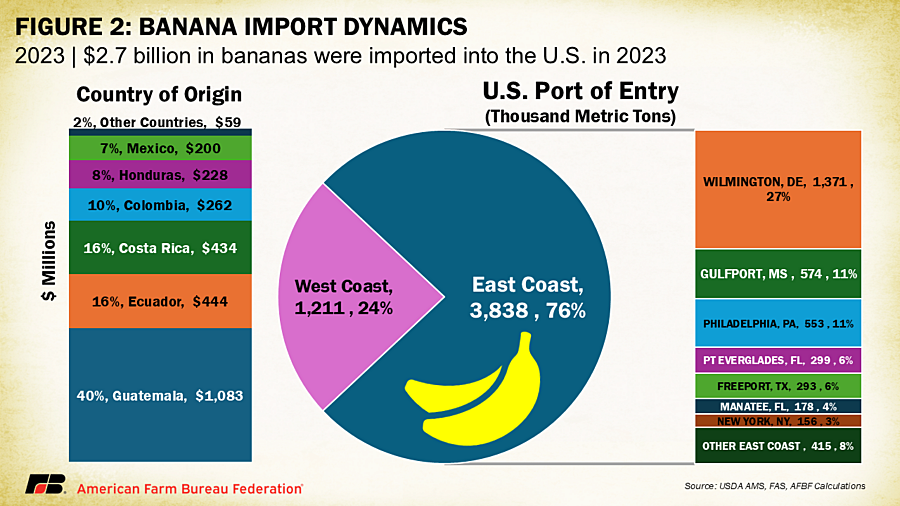

In January 2024, the U.S. imported $231 million worth of bananas, equating to approximately 422,000 metric tons. Of these, 76% entered through containerized East Coast ports, with Wilmington, Delaware, alone handling 26% of the total. On an annual basis, this corresponds to over 3.8 million metric tons of bananas entering ILA-handled ports, with 1.4 million metric tons flowing through Wilmington.

Most bananas consumed in the United States are grown in Central and South America. In 2023, Guatemala supplied 40% of U.S. bananas by value, followed by Ecuador and Costa Rica, each contributing 16%. From harvest to store shelf, bananas have a narrow window of about two weeks, underscoring their perishability. In the event of a second ILA port strike, bananas could quickly become scarce, with potential disruptions to availability within just a few days. Alternative routes, such as rerouting from West Coast ports or transporting via rail across Central America, are impractical given the time-sensitive nature of banana logistics.

The Seasonality Factor

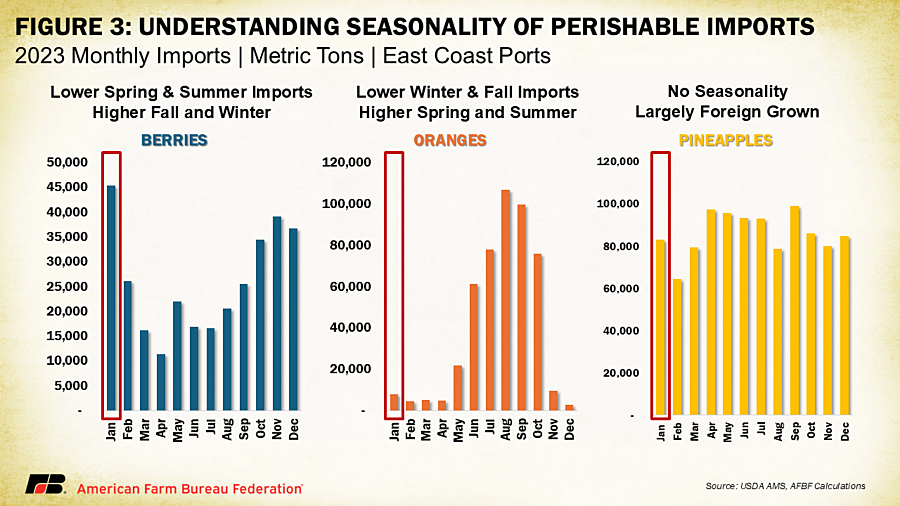

When assessing the potential impacts of an ILA strike on perishable food products, it is essential to also consider the timing within the agricultural calendar. The month of the strike can significantly influence its severity, depending on the availability of domestic supplies for certain agricultural goods. When domestic fresh supply is unavailable, imports often fill the gap, making timing a crucial factor in assessing trade disruptions.

Figure 3 highlights this seasonal dynamic. Berry harvests vary widely across the U.S. by variety and region, but there is generally a domestic shortage during the winter months. During this time, shipments of blueberries from Peru, for example, increase significantly to meet consumer demand. Conversely, oranges have robust domestic availability during the winter and spring, with imports peaking in the summer and fall to supplement supply. Pineapples, on the other hand, have a different pattern. With domestic production limited to Hawai’i and Puerto Rico, pineapple imports remain steady throughout the year with little seasonality. In this context, a January ILA port strike would jeopardize a large share of berry and pineapple imports while having a comparatively smaller impact on orange imports.

The Automation Divide: Labor and Efficiency

Since the tentative agreement was reached in October, much of the media focus has centered on automation within port facilities — a key unresolved issue between the ILA and USMX. Article XI of the existing ILA Master Contract, section one, part A explicitly states, “There shall be no fully-automated terminals developed and no fully-automated equipment used during the term of this Master Contract. The term ‘fully-automated’ is defined as machinery/equipment devoid of human interaction.”

The ILA, representing nearly 85,000 dockworkers, opposes efforts to automate port facilities given the significant potential impact on dockworker jobs. The union argues that automation threatens not only their members’ livelihoods but also the economic vitality of port communities, where dockworker wages support local businesses and families.

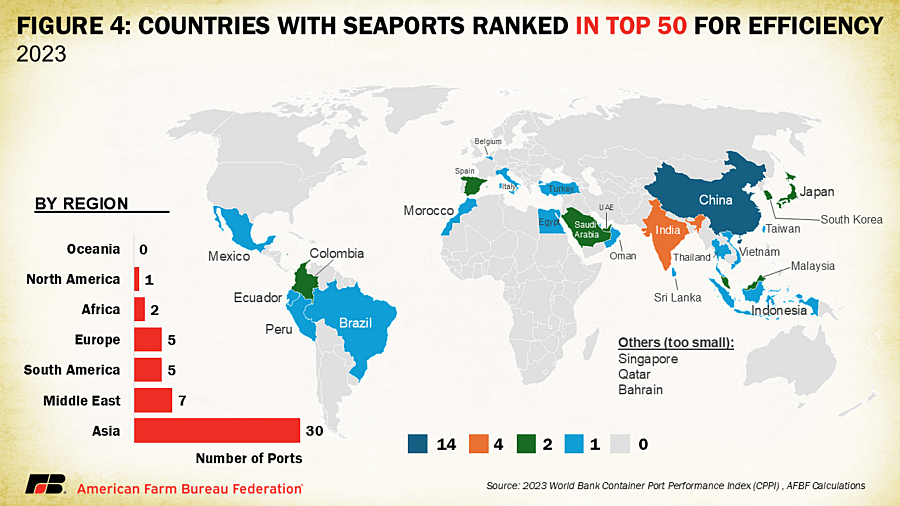

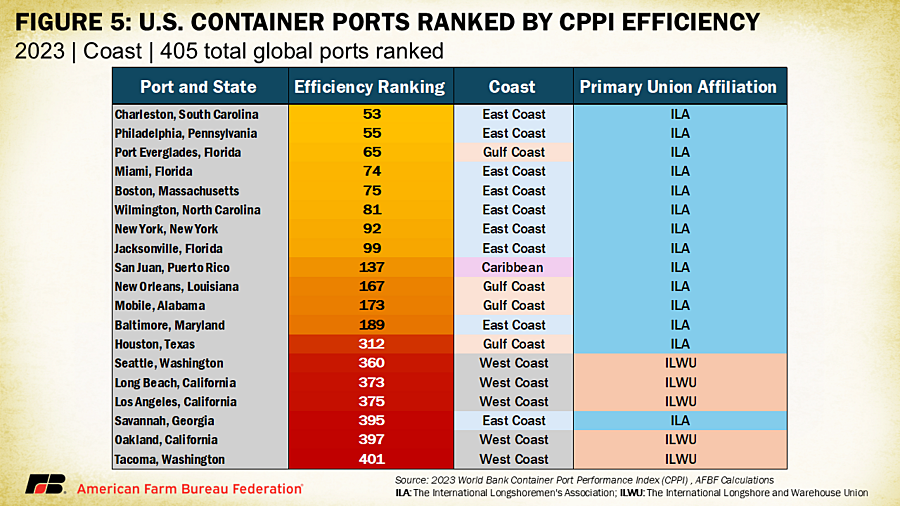

Despite being critical gateways for global trade, many U.S. container ports rank among the least efficient in the world, with none in the top 50 and six languishing in the bottom 50 out of 405 ports total in the World Bank's 2023 Container Port Performance Index (CPPI). The CPPI evaluates ports based on vessel time in port, requiring a minimum of 24 valid port calls — measured from arrival at port limits to departure after cargo operations — to ensure statistically significant and comparable data. Despite robust infrastructure and substantial resources, U.S. ports have consistently underperformed compared to many of those in both developed and developing nations.

For instance, ports in countries such as China, Oman, Colombia and Vietnam surpass major U.S. ports in efficiency (see Figure 4). The highest-ranked U.S. port, Charleston, comes in at number 53 out of 405. Meanwhile, all major U.S. West Coast ports, along with Houston and Savannah, rank in the bottom 100 globally (Figure 5). Notably, East and Gulf Coast ports staffed by ILA workers generally demonstrate better performance compared to their West Coast counterparts managed by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). However, this is a modest achievement, given that many of the top 50 efficient ports are in developing nations.

A second strike would likely rekindle the contentious debate over automation at U.S. ports, where restrictions on adopting advanced technologies have already hindered productivity. The lack of automation at many U.S. ports has contributed to inefficiencies, including extended berth times and suboptimal operations, which in turn drive up costs for both shippers and consumers. These challenges underscore the urgent need for modernization to enhance competitiveness and efficiency.

How was Agricultural Trade Impacted by Port Strike Round One?

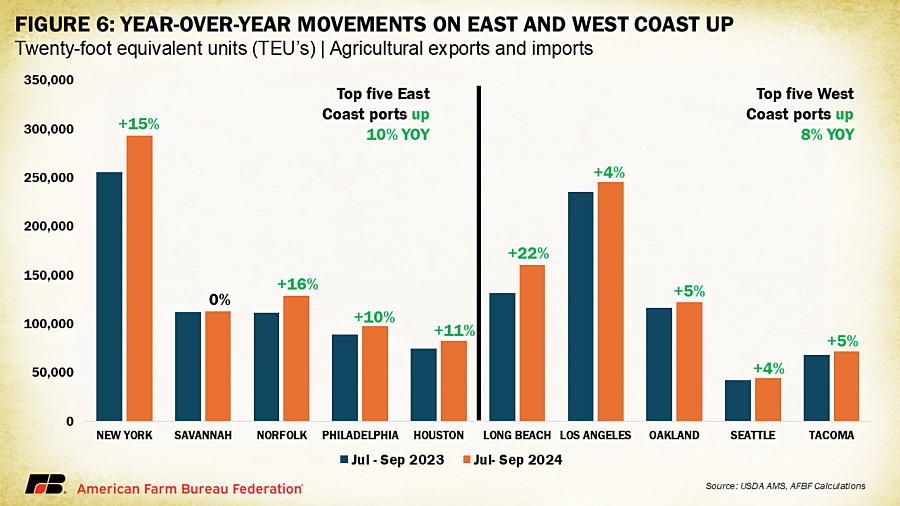

In our previous analysis, agricultural trade data indicated a shift from East Coast to West Coast ports. Between May and June 2024, agricultural trade increased by 18% across the top five West Coast ports while declining by 10% at the top five East Coast ports compared to the same period in 2023. However, this trend did not persist later in the year — even in the lead-up to the strike. Year-over-year agricultural trade between July and September 2024 was up 8% on the West Coast and 10% on the East Coast (Figure 6).

This shift may reflect shippers’ and retailers’ proactive efforts to deliver goods ahead of a potential strike. Separate USDA Foreign Agricultural Service data reveals that even in October 2024, when the port strike occurred, trade numbers across East Coast ports remained strong, with agricultural imports up 19% and exports up 4% compared to October 2023. Time will tell how these trends change leading up to Jan. 15.

Conclusion

We’ve previously highlighted the vital role East and Gulf Coast ports play in connecting U.S. farmers to critical foreign markets and the lasting damage even a week-long strike could cause. As the Jan. 15 deadline approaches, consumers and farmers alike should consider which products are most at risk — and why. From highly perishable imported goods like bananas and fresh seafood to staple agricultural exports like cotton and poultry, the potential for disruption highlights the critical need to address inefficiencies and secure the resilience of U.S. supply chains.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL