Beefing Up Dairy: The Rise of Crossbreeding

Daniel Munch

Economist

Beef-on-dairy crossbreeding is the latest step in the evolution of dairy genetics and is now a key driver of the U.S. supply of both beef and dairy cattle. Some 72% of dairy farms are now incorporating beef genetics into their breeding programs, enhancing the marketability of dairy-origin calves by improving carcass quality and feed efficiency — traits highly valued by feedlots and packers. Crossbreeding, along with the widespread use of sexed semen, is helping stabilize beef supply while creating a reliable revenue stream for dairy producers. This article examines the rapid expansion of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding and its growing economic influence across the dairy and beef industries.

Background: A Shift in Breeding Strategies

Historically, dairy farmers bred their herds using dairy bulls in the herd, ensuring a steady supply of replacement heifers. Bulls were otherwise unable to contribute to milk production but made up about half of the calves born, so all but the best were sold into the beef market for veal, since they otherwise held little value in the beef market due to their lighter muscling and lower-quality carcass traits. The introduction of artificial insemination (AI) in the mid-20th century revolutionized dairy breeding, allowing farmers to access superior genetics without the need for on-farm bulls — except for "clean-up" to ensure all cows are bred. This innovation allowed producers to improve milk yields and herd efficiency while reducing the logistical and safety challenges associated with housing and maintaining bulls. During this period, breeding efforts remained centered on dairy genetics to enhance milk production, while surplus male calves continued to be sold for veal, which was falling out of favor with consumers.

The advent of sexed semen in the 2000s further refined breeding strategies by allowing farmers to selectively produce heifers by pairing the best bulls with the best cows in the herd. Meanwhile, lower-performing cows were still bred — often with any available bull — not to improve genetics, but simply to ensure they calved again and remained in milk production for another cycle. This shift also allowed dairy farmers to take advantage of the emerging market for beef-on-dairy crossbred calves through AI. Once the opportunity became clear, they began using high-quality sexed semen on their best dairy cows to maximize milk production while breeding the rest of the herd with high-quality beef semen. This approach produced calves with better muscling and carcass quality while maintaining a productive and efficient dairy herd.

This shift has fundamentally changed the economic landscape of dairy farming. Male dairy calves, once a liability, are now a valuable revenue source. Beef-on-dairy crossbreeding allows farmers to command premiums for their male calves, offering a financial cushion against volatile milk markets. Between 2002 and 2019, researchers from the University of Wisconsin estimated that dairy-origin animals, including finished dairy steers (castrated male cattle), beef-on-dairy crossbreds and cull cows, account for 18% to 24% of U.S. beef production.

Economic Implications of Beef-on-Dairy Crossbreeding

Beef-on-dairy crossbreeding can provide significant economic benefits to dairy farmers. Unlike purebred Holsteins, which face heavy beef market discounts, crossbreds offer consistent carcass traits that better meet packer and consumer expectations. Additionally, these calves convert feed more efficiently than purebred dairy steers, reaching market weight at lower cost and ultimately lowering the overall resource footprint of beef production.

A 2024 survey completed by Purina found that 80% of dairy farmers and 58% of calf raisers receive a premium for beef-on-dairy calves compared to pure-bred dairy calves, with some reporting additional revenues of $350 to $700 per head. These premiums have helped offset lower revenues during periods of reduced milk prices and provided dairy farms with a diversified income stream. Crossbred calves also achieve higher quality grades compared to traditional dairy steers, increasing profitability at the feedlot level.

Additional Purina research highlights the widespread adoption of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding across the dairy industry. Among surveyed producers, 72% reported they are actively implementing crossbreeding programs, while another 16% indicated they are not yet involved but are considering it. Six percent stated they had previously engaged in crossbreeding but are not currently participating and only a small fraction — 6% — expressed no interest in adopting the practice.

For the beef industry, the rise of beef-on-dairy programs has been timely. With the U.S. cattle inventory at its lowest level in 73 years, crossbred calves sourced from dairy farms have become a critical source of supply. These calves help fill the gaps left by declining beef cow numbers, which have been exacerbated by years of drought-induced herd liquidations across the central Plains and the West. As beef-on-dairy crossbreeding becomes a key part of the beef supply chain, measurable indicators confirm its rapid expansion and growing influence.

Trends Supporting the Growth of Beef-on-Dairy

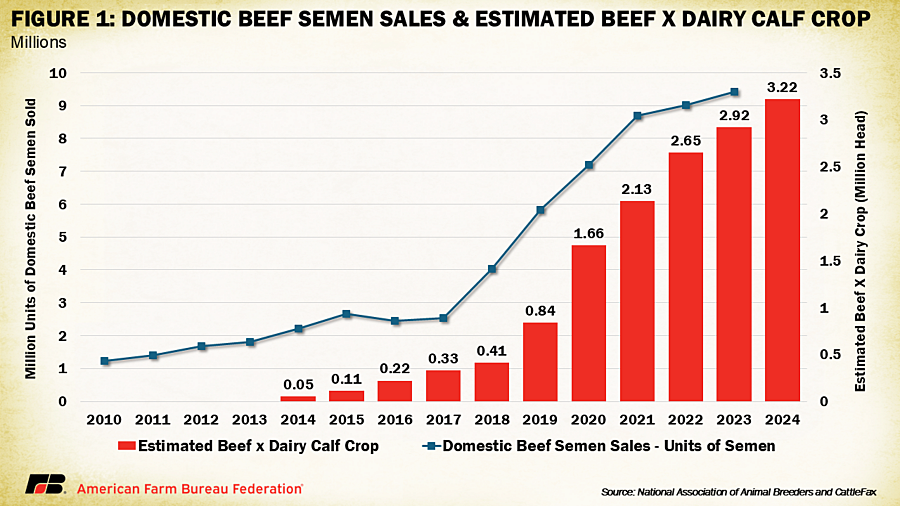

The rapid growth of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding is evident in several key metrics. One major indicator comes from data provided by the National Association of Animal Breeders, which tracks the sale of semen used for artificial insemination in cattle. Domestic sales of beef semen have surged from 1.2 million units in 2010 to 9.4 million units in 2023. Of these sales, 7.9 million units were used in dairy cattle, while only 1.5 million units were used in beef herds. This increase reflects the growing adoption of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding among dairy farmers, who are using beef semen to produce calves with greater market value. CattleFax estimates crossbred calf production rose from just 50,000 head in 2014 to 3.22 million in 2024. (Figure 1).

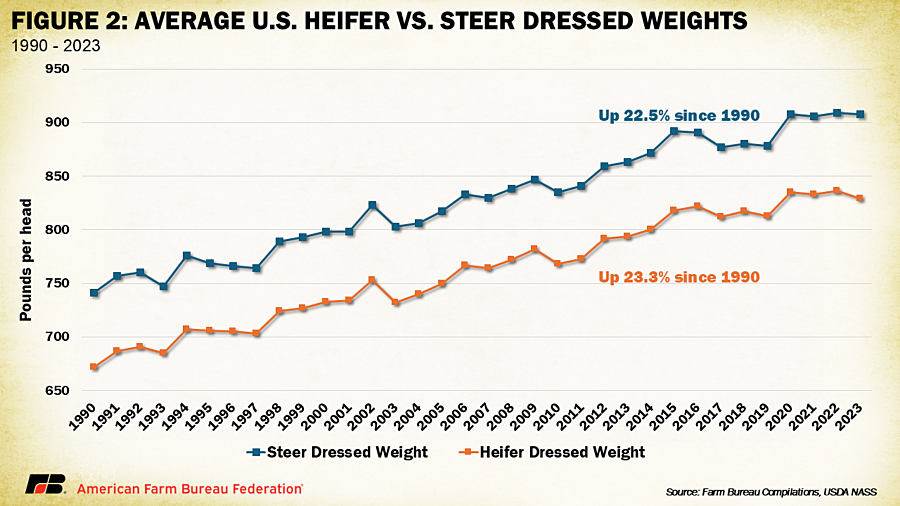

Meanwhile, dressed weights for steers and heifers (young female cattle that have not calved) have steadily increased, which can be at least partly attributed to the genetic advantages of crossbreeding. Dressed weight refers to the weight of an animal's carcass after inedible parts have been removed for retail or further processing. All steer dressed weights rose from 741 pounds in 1990 to 908 pounds in 2023 (+22.5%), while heifers increased from 672 to 829 pounds (+23.3%). These improvements partly reflect enhanced muscling and carcass quality in beef-on-dairy calves, which yield more lean red meat and higher-value products than pure dairy breeds. Genetic gains not only improve processing efficiency for packers who get more meat per animal but also enhance feedlot performance and profitability, ultimately delivering greater market value for dairies. Lower feed costs and strong beef prices have also encouraged feeders to push cattle to heavier weights more broadly, meaning these gains aren’t solely driven by beef-on-dairy crossbreeding.

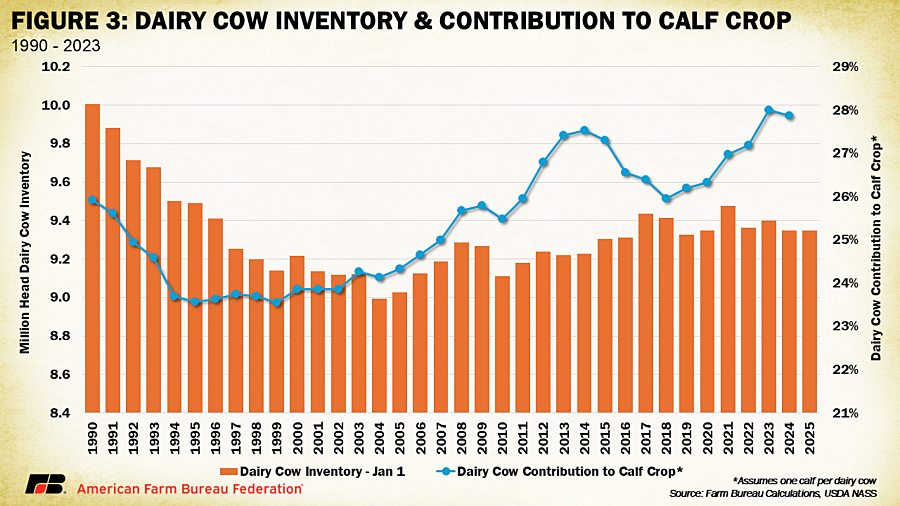

Identifying additional metrics to gauge the use of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding presents a challenge, as USDA does not specifically track these crossbred animals within the supply chain. One option is comparing dairy cow inventory numbers to the overall calf crop. Assuming one calf per dairy cow, one can estimate dairy cow contribution to the total cattle calf crop annually. Between 1990 and 2023, dairy cow inventories declined by 660,000 head (6.6%), going from 10.1 million to 9.35 million. The calf crop during the same timeframe declined by 5.1 million head or 13.1%, dropping from 38.6 million to 33.5 million. The dairy cow contribution during that period started at 26%, dropped to 24% by 1995 and has since increased steadily to 28% as both dairy cow inventories and the total calf crop have declined. This trend highlights the increasing reliance on dairy-origin calves to bolster the beef industry, driven by a shrinking beef cow herd and the growing adoption of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding, which contributes to a more stable beef supply.

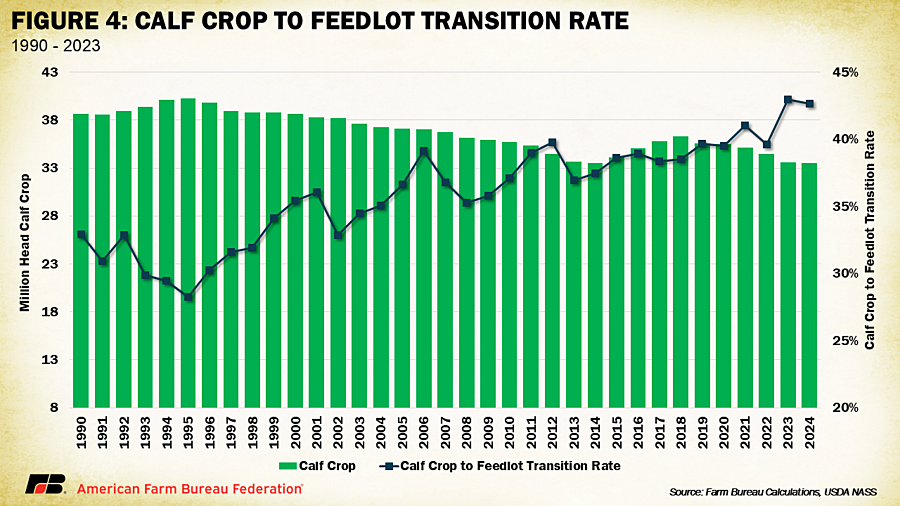

Additionally, the proportion of calves transitioning from farm inventory to feedlots can be estimated by dividing the number of cattle on feed by the previous year’s calf crop. This metric helps assess whether a greater share of calves is moving into feedlots earlier rather than being retained for breeding or other uses. In 1990, about 33% of the calf crop transitioned directly into feedlots, but by 2023, this figure had climbed to 43%. Some of this increase is likely tied to strong beef prices, which incentivize producers to market calves for beef rather than retaining them for breeding or future sales. Additionally, the sharp decline in veal production — calf slaughter dropped from 1.79 million head in 1990 to just 293,600 head in 2023, a 84% decline — has likely redirected more dairy-origin calves toward beef production rather than traditional veal markets. The rising share of dairy-origin calves, particularly beef-on-dairy crossbreds, eventually entering the feedlot system has further contributed to the long-term increase in cattle on feed.

This metric does have limitations. Calves are not placed in feedlots immediately after birth, with a typical lag of six to 12 months between birth and feedlot placement. As a result, some of the previous year’s calf crop may not enter feedlots until the following year, complicating direct comparisons. Additionally, dairy and beef calves historically do not enter feedlots at the same rate, as purebred beef calves often remain on pasture longer before transitioning, while dairy calves — especially crossbreds — are more likely to be placed in feeding systems at an earlier stage. Despite these nuances, this trend suggests that as beef cow numbers decline, feedlots are relying more heavily on dairy-origin calves to maintain supply, reinforcing the growing economic significance of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding in both the dairy and beef sectors.

Potential Implications for Milk Markets

The rise of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding may also have significant long-term effects on milk price dynamics. Historically, when milk prices rose, dairy farmers expanded their herds by retaining more replacement heifers, increasing milk production. However, this cycle often led to an oversupply of milk, eventually pushing prices back down. With more dairy farmers now using beef semen on a portion of their herd, the number of purebred dairy heifers being raised has declined, inherently slowing the industry’s ability — and perhaps desire — to rapidly expand milk production in response to modest price increases.

This shift represents a fundamental change in risk management for dairy farms. Instead of being fully exposed to the volatility of the milk market, dairy producers now have an alternative revenue stream through beef-on-dairy crossbreeding. This dynamic could help stabilize milk markets by naturally curbing oversupply during periods of high prices, creating a more balanced production cycle.

Today, exceptionally high beef prices are reinforcing this trend, as more dairy farmers opt to breed beef-on-dairy calves to capture what appears to be a more reliable and immediate return. As a result, fewer dairy heifers are being raised, further limiting the potential for rapid milk production expansion in the near term.

Conclusion

The widespread adoption of beef-on-dairy crossbreeding is transforming both the dairy and beef industries, creating new economic opportunities for farmers while addressing supply challenges in the beef sector. By leveraging genetic advancements, including artificial insemination and sexed semen, dairy producers can now produce crossbred calves with improved beef traits, enhancing market value and offering a reliable revenue stream beyond milk production. As dairy-origin crossbreds become essential to U.S. beef supply, they are reshaping cattle production and potentially providing better price and supply stability to both markets. Beef-on-dairy strategies will continue shaping herd management, markets and risk mitigation in livestock production.