Conservation Practices Not a One-Size-Fits-All

TOPICS

Conservation

Samantha Ayoub

Economist

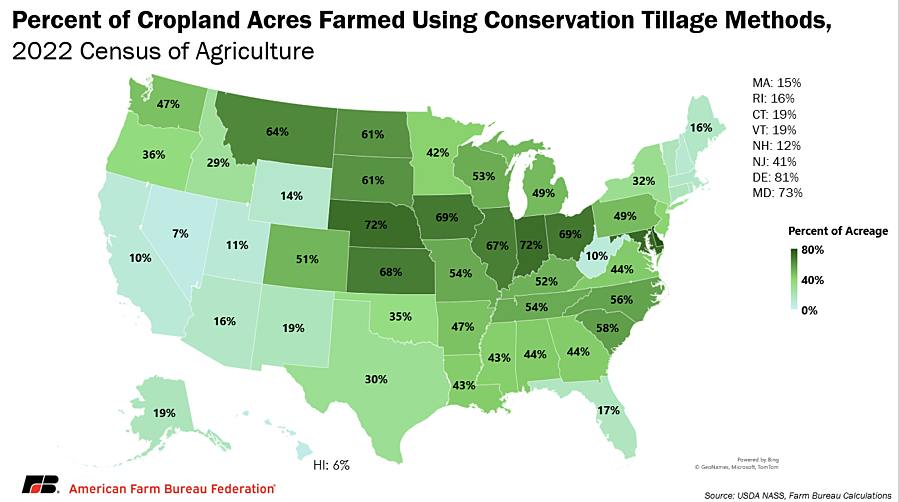

Any conservation discussion will include cover cropping and conservation tillage use at the forefront. According to the 2022 Census of Agriculture, conservation tillage, including no-till, is used on 53% of America’s cropland, making it the most-used conservation practice. Meanwhile, cover crops are planted on just under 5% of all cropland, and adoption is more regionalized, highlighting the challenges that come with adopting this management system. So, what drives the focus on cover cropping? And why do these two practices steal the spotlight in conservation-related policy?

Cover Cropping

Cover cropping involves growing various plant varieties between cash crop rotations to ensure continuous soil coverage. This practice improves soil water infiltration, builds soil organic matter, prevents soil erosion, restores soil nutrients and manages pests by increasing root channels, plant diversity and soil cover in fields.

Under USDA definitions, cover crops are not harvested and sold (except for forage in limited emergency circumstances) but are terminated in various ways including natural frost, burning, applying herbicides, and flattening (“rolling”) or tilling them before planting the primary crop. Termination methods must be carefully considered as all these approaches have risk. Frost may not kill the plant, causing competition with the primary crop; burning can sacrifice much of the soil health and carbon retention benefits of cover cropping; using herbicides comes with the risk of adding to herbicide-resistant weed populations; and rolling or tilling can worsen soil compaction.

Cover crops are incentivized through various USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) programs such as the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), programs that fund cover crop adoption and set guidelines for practice management. While USDA-Risk Management Agency (RMA) does not financially cover the planting of cover crops, the agency includes cover crop usage among allowed Good Farming Practices (GFP) as of 2024. Farmers must employ GFPs to receive full indemnity payments to prevents farmers from incurring crop insurance compensation due to management-induced yield losses. Until December 2023, NRCS conservation practices were not considered GFPs if they negatively impacted crop growth, so short-term yield effects while fields adapted to cover cropping could be penalized under RMA insurance requirements. Including NRCS conservation practice procedures in the updated 2024 GFP guidelines removes one barrier to cover crop adoption for RMA insurance users.

Cover crops financed under NRCS programs may be used as extra livestock forage either through grazing or cutting for hay or silage – which in this case may be sold. However, haying and grazing are limited if the farmer is participating in the RMA summer fallow program or the state-focused EQIP Soil Health Initiative. Keeping track of these differences between agencies and program requirements adds a hurdle for participating farmers.

Double Cropping

Double cropping differs from cover cropping only in that both commodities grown are harvested for money at different points in the year – for example corn and winter wheat. Double cropping provides many of the same benefits as cover cropping – continuous soil coverage, living root systems and nutrient building. By growing more food, fiber and fuel on existing cropland, this practice also increases farming productivity. Yet, double cropping is not considered a conservation management practice under USDA program eligibility.

Cash crops, including those grown through double cropping, are eligible for RMA insurance policies. The distinction between “cover cropping” and “double cropping” prevents double payment from USDA for the same field activity as a field growing cash crops year-round is under continuous insurance coverage. RMA expanded their double cropping coverage area in 2023 to encourage increased food production, recognizing the benefits of continuous cash crop production.

While both provide conservation benefits, the arbitrary differences between double cropping and cover cropping can affect the management decisions of farmers attempting to provide continuous soil coverage. If farmers hope to make a monetary return on their decision to continuously cover their field (the goal of cover cropping) by planting a valuable crop such as wheat outside of their typical crop rotation, they are not being recognized for their contributions to conservation efforts. Double cropping acres are not explicitly recorded in the Census of Agriculture. Instead, the same acres on which two crops are grown are counted to the total harvested acres of each individually, meaning that the total number of harvested cropland acres in the census adds up to more than the total acres of U.S. cropland used for production. The administrative distinctions between double cropping and cover cropping thus prevent us from tracking the true number of acres that are benefiting from the soil health advantages of continuous plant coverage.

Tillage

Tillage is traditionally used to loosen the soil and remove surface residue to improve seed planting. Conservation tillage – either no-till or reduced tillage – reduces soil disturbances that cause soil compaction or reduce soil cover, which can both exacerbate erosion. Conservation tillage limits soil compaction from tire pressure by reducing the amount of times machinery is driving over the field to prepare for planting. Instead of clearing the field cover to plant directly into the soil, conservation tillage methods create channels through previous years’ biomatter to plant seeds, moving as little soil as possible. No-till requires planters that cut into the soil and deposit seeds directly into the ground while other minimum tillage practices like strip till, ridge till and mulch till keep at least 30% of the soil surface covered in plant residue. The practice also reduces carbon emissions by reducing the amount of equipment passes on each field; according to USDA’s estimate, between 2013 and 2016 conservation tillage reduced fuel use by 763 million gallons per year which reduces carbon dioxide emissions by 8.5 million tons.

Used individually or in conjunction with each other, cover crops and conservation tillage cover all the pillars of soil health management: minimize soil disturbance, maximize soil cover, maximize biodiversity and maximize the presence of living roots in the soil.

National Adoption

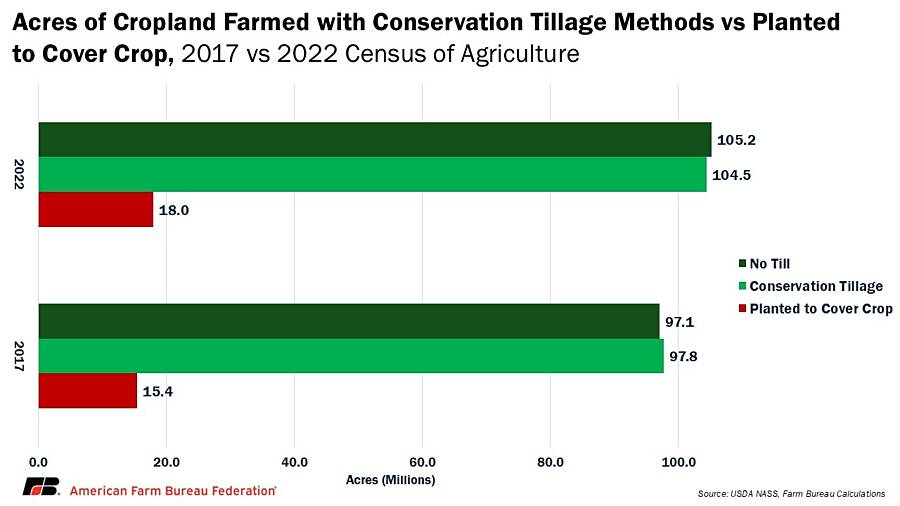

Total land farmed in the U.S. is down over 20 million acres in 2022 compared to 2017, when the previous Census of Agriculture was conducted. However, acreage for all three practices – conservation tillage, no-till and cover cropping – increased between the two censuses, now reaching 25%, 28% and 5%, respectively.

The Inflation Reduction Act committed $19.5 billion over five years for USDA conservation programs with climate change mitigation benefits. NRCS made its largest commitment of assistance under these programs in 2023 with over $2.8 billion spent on more than 45,000 contracts. Some of these programs include conservation easement development, technical assistance for in-field training, the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) to collaborate with partners and on-farm practice funding through EQIP or CSP. Individual practice adoption was tied to $1.4 million in outlays in fiscal year 2024 for over 330,000 new conservation practice uses. Cover cropping is the fifth-most-used practice under obligated contracts in fiscal year 2024. Conservation tillage contracts do not make the top 30 practices supported under these programs, showing a slowdown in adoption growth.

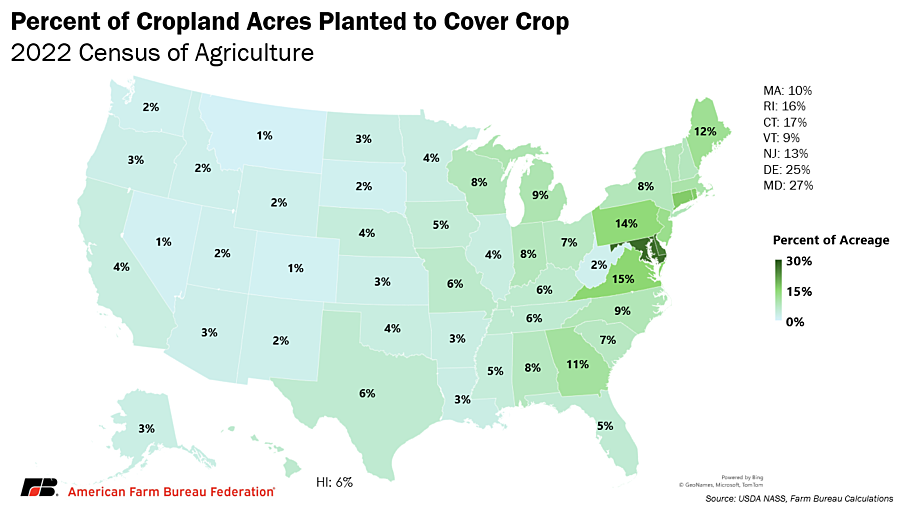

Cover cropping was used on just under 18 million acres nationwide, a nearly 17% increase between 2017 and 2022 – double the growth rate of conservation tillage methods. Cover crop adoption is largely driven by regional shifts as weather conditions, water availability and soil type all impact regional suitability for cover crops.

Challenges

As with any new (or newly appreciated) technology, acceptance of conservation practices can take time. Farmers’ attitudes toward risk, social acceptance, expectations of effort, the local soil and weather conditions, and the length of time before soil health benefits can provide bottom line benefits can all affect the likelihood of adoption, and none of these practices is likely to reach 100% adoption.

Cover cropping and conservation tillage both have technical limitations. Farmers’ primary concern with conservation tillage is increased pest presence as tillage typically serves to eradicate weeds and other pests. If significant residue is left from the previous year’s crop, it may also be difficult to cut through to plant the next crop. Special no-till planters are required to cut through this residue, which can be a substantial initial investment to begin using conservation tillage.

Cover crops come with significant labor and financial investments over their entire use – new equipment, planting time and termination management. It will often take a long-term commitment to see benefits from the practice, so the initial costs are a significant barrier to entry. In fact, cover crops can initially hurt yields as the plants use soil nutrients before they decompose and add back to the organic matter. So, in the first few years, additional inputs like fertilizer or irrigation are needed to replenish the nutrients being used by additional plant growth on a field. In down farm economies like the current one where farmers already face high production costs and low revenues, it may be difficult to justify these additional expenses.

Additionally, different soils, climates or primary crops can affect the land’s suitability for different cover crops and management systems. Areas with limited rainfall might not have enough moisture to sustain multiple plants. If not enough soil water is left after growth of a cover crop, that can prevent growth of a cash crop later in the year. In cold climates, increased water retention in the soil from runoff prevention can also delay soil warming and the planting of the cash crop. Each primary crop also has different cover crop compatibility. Fields for crops such as corn have a high level of residue left on the surface after harvest, while some, like cotton, do not leave significant residue. High-residue crops, while missing living roots of cover crops, do not have the same bare soil that worsens erosion, especially if being managed with conservation tillage. These considerations all combine to specific growing condition requirements for effective use of cover crops: a light residue left over from the primary crop in a climate with adequate weather and longer, warmer growing seasons.

The technical components can make cover cropping a significant managerial burden, so extensive training and support is needed to learn how to effectively utilize the practice. The different rules for each USDA programs’ eligible cover crop varieties, planting and termination procedures can also make it difficult to develop a suitable plan. After five years, farmers are also no longer eligible for EQIP funding for cover crop implementation. Additionally, any farmers who have been implementing conservation practices prior to receiving assistance lose their eligibility for conservation funding. This punishes early adopters by limiting their financial options to maintain conservation management. Instead, they may enroll in CSP, but this program requires combinations of practices and advancements beyond “basic” practices – for example, planting cover crop mixes rather than one plant. This program can be difficult to participate in due to the extensive technical expertise needed to implement these “bundles” of practices.

Other programs may require using multiple conservation practices in conjunction – referred to as “bundling.” The most prominent example of this is the requirements for farmers growing corn and soybeans to become feedstocks for sustainable aviation fuel. To be eligible for the IRS 40B tax credit for contributing to climate change initiatives, both corn and soybeans must be farmed with no-till and cover crops. Corn must also use specific enhanced-efficiency fertilizer to reduce nitrogen emissions. As we have discussed, cover crops adoption is limited; so most farmers were ineligible for these credits, leaving feedstock demand to overseas sources. Every additional requirement intensifies the management factors and expertise needed to participate, creating serious barriers to entry for these programs whose aim is broader adoption of conservation practices.

Regional Adoption

The East Coast has the highest level of adoption by acreage. Ten states on the Eastern shoreline have the only double-digit percentage share of cropland planted to cover crops, but many of these are Northeastern states with less cropland farmed overall. The Great Plains states have the greatest growth rate in cover cropping despite having some of the largest decreases in overall acres farmed. However, no state west of the Mississippi River has more than 6% of its cropland planted to cover crops, and 22 states nationwide have less than the national average of 5% of cropland planted to cover crops.

Local initiatives targeting specific fragile environments such as highly erodible land or watersheds with runoff-related water quality issues are significant contributors to cover crop adoption. Maryland has had the highest adoption rate for cover crops, with 27% of all cropland planted to cover crop in 2022 due to long-standing commitments to improve water quality in the Chesapeake Bay. More recently, the Environmental Protection Agency set benchmarks for water quality improvements in the Mississippi River basin (MRB) specifically targeting nutrient runoff. Each state in the MRB has developed nutrient reduction strategies for their watersheds, and many rely on research and implementation projects and partnerships to increase conservation practices in their states. Cover crops are a significant resource in combating nutrient runoff because they prevent erosion and promote nutrient retention in the soil. Thirteen of the 15 MRB states increased cover crop adoption from 2017 to 2022. There are some states and watersheds that entered RCPP contracts with NRCS to target conservation funding to at-risk watersheds.

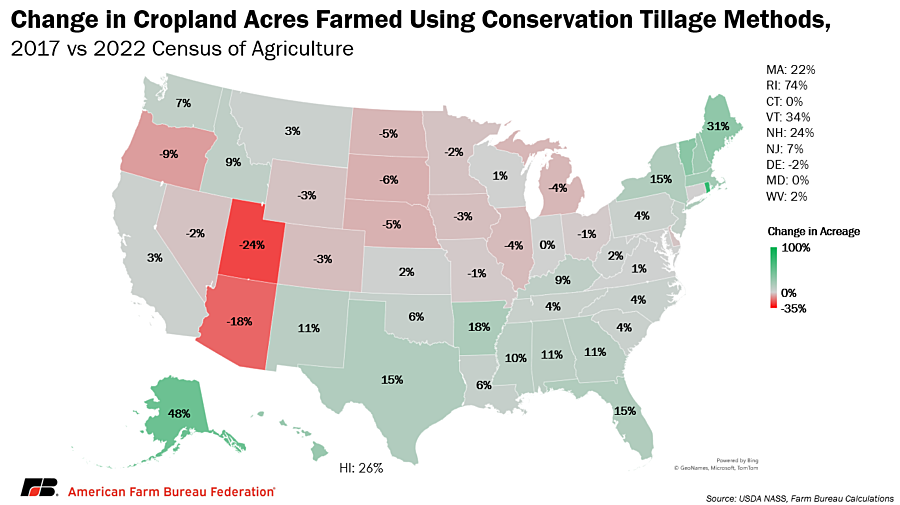

Conservation tillage methods are more widely adopted than cover cropping. Combined, no-till or reduced tillage is used on over 200 million acres of cropland nationwide, nearly equally split between no-till and reduced tillage. No-till and other forms of conservation tillage increased 8% and 7%, respectively. Many farmers use tillage as a pest management tool to eradicate weeds and insects, so reduced tillage was historically more popular. But in 2022, no-till acreage overtook other forms of conservation tillage, showing a growing acceptance of more intense conservation tillage methods through the previous five years. The economic benefits of reduced tillage likely incentivized practice adoption since removing the intensive tillage requirements of traditional methods can save money on fuel, labor and equipment. Overall, acreage farmed with conservation tillage is more consistent between 2017 and 2022. Most states have only single-digit percentage point growth or lower rates in conservation tillage acres. As these practices are already more widely used, it is likely adoption has plateaued.

Conclusion

The variety of environmental conditions across the country means field compatibility with different conservation practices will vary too. Beyond climate and soil types, adoption of these conservation methods is also impacted by financial and farm management factors. Cover cropping can be especially challenging due to the additional inputs required and management intensity of the practice. The lack of USDA program support for double cropping may be encouraging cover cropping in cases where the conservation benefits of double cropping (including reduced acreage requirements for food production) might be greater. We are seeing increased adoption of cover cropping year-over-year, highlighting the commitment of American farmers to conservation efforts. While it is encouraging to see growing adoption of conservation practices, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for the diverse regions and production types of American agriculture.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL