Echoes of ’80s Farm Crisis in Current Economy

TOPICS

Farm Economy

Bernt Nelson

Economist

Facing tumbling commodity prices and livestock prices that are a mixed bag at best, American farm families are struggling to keep their heads above water; and the farm bill that is supposed to provide a safety net for times like this is not there to protect them. Many aspects of today’s economy have us pointed in a direction similar to the farm crisis of the 1980s, but it’s not too late to avoid that.

This Market Intel details the economic landscape for farmers and some ways in which it is similar to the farm economy crisis of the 1980s. It will build on several past Market Intel reports and be followed by another that will lay out the leadership traits and actions that can help weather this storm.

State of the Economy

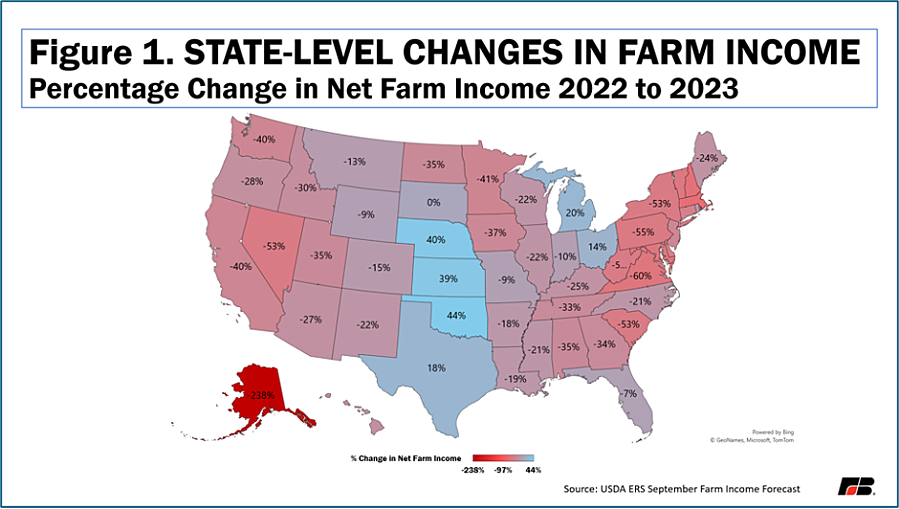

USDA’s September farm income forecast estimates that 2024 net farm income will fall 4.4% from 2023 to $140 billion. More alarming, net farm income has fallen 23%, or $42 billion, in just two years. Overall, states with more crop production are forecasted to have a bigger drop in income compared to states with more livestock production (Figure 1). While livestock prices have been a mixed bag, livestock receipts are expected to rise by 7.1% on the back of stronger-than-expected prices in cattle, eggs and dairy.

Farmers’ Struggles Go Beyond Finances

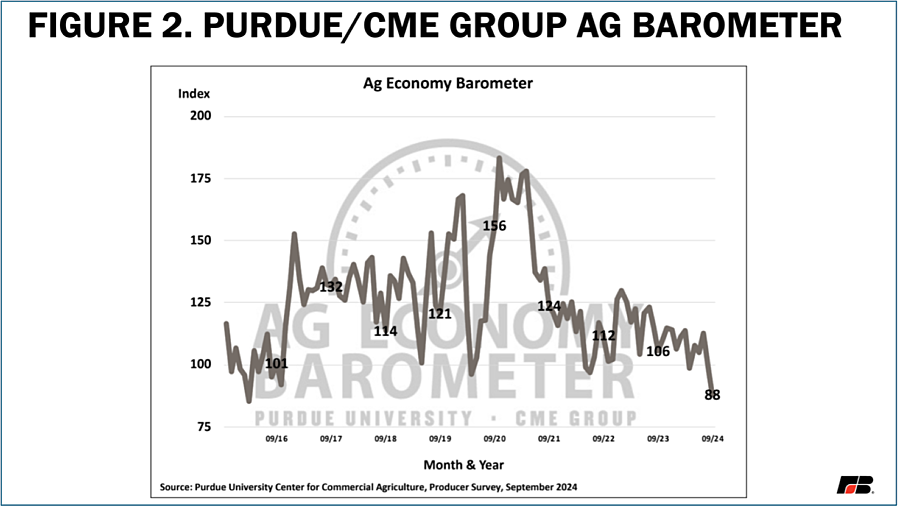

According to Purdue University/CME Group Ag Economy Barometer’s September report, which is based on a monthly survey of producers, farmer sentiment fell dramatically in one month to its lowest level since the ag economy downturn in 2016. (Figure 2)

Prices

Row Crops & Grains

Spring’s favorable planting conditions and summer’s good growing weather is resulting in robust yields and a growing supply of many U.S. row crops. USDA’s World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report, released on August 12, estimates record-setting and well-above-trend yields for many crops, including corn, soybeans and wheat, pushing prices near 2020 lows.

Basis is the difference between a futures price or a standard market point price for a commodity and the local cash price actually being offered for that commodity. Basis varies by geographic region and is sensitive to events that disrupt or increase costs for shipping. Corn and soybean stocks are up 30% over last year, leaving farmers and buyers short of storage space and creating widening and more uncertain basis. These large stocks combined with the monster harvest being brought in could drive grain buyers to slow delivery and reduce the farmers’ price. Supply chain disruptions, including the recent port strike, Mexican rail stoppages, low water in the Mississippi River and the impacts of Hurricane Helene’s devastation, all add even more risk to this scenario, as it upends normal time and distance relationships.

Livestock

The U.S. cattle inventory is at a 73-year low as result of drought, inflation and high supply costs all driving farmers to sell cattle. This pushed beef prices to record levels in July. Packers have slowed slaughter pace, while lower prices for feed grains have incentivized feeding cattle to heavier weights. USDA’s September WASDE estimates the average 2024 price for fed steers is $185.11, up 5% from last year but down 1.5% from a month ago.

Hog prices have recovered some from 2023, when average losses for farrow to finish farms were estimated at $31 per head, but slow demand and elevated costs have minimized profits. It could take years for hog farmers to make up for 2023’s losses.

Poultry & Eggs

At an estimated $1.28 per pound, 2024 broiler prices would be unchanged from 2023. Table egg production in 2024 is estimated to be 7.8 billion dozen table eggs, down about .8% from 2023. This change reflects the smaller layer inventory from the outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza in 2022. Lower production has pushed wholesale egg prices higher. The average New York daily wholesale price for large eggs was $4.01 per dozen in August and is the highest monthly average since egg prices hit record highs in December 2022. Egg receipts, originally forecast to drop by 12%, are now expected to surge by 38.7%.

Costs

While many commodity prices have fallen, the cost of production is far above pre-pandemic levels. Drought conditions fueled a market rally in grains from 2020-2022, but farmers and consumers alike were facing another rally during this time, inflation. Following a short but severe recession caused by COVID-19-related supply shutdowns, the Federal Reserve increased the money supply by 42% in just 22 months using a combination of low interest rates and “quantitative easing.” The result of this oversupply of money was the highest inflation we had seen in nearly 40 years. The impact on farmers was immediate, with prices for supplies such as chemicals, equipment and seed headed to new highs. Fertilizer prices hit record levels in April 2022 following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. According to USDA’s farm income summary, total production expenses are now forecast to decrease slightly, by $4.4 billion (1%), following three consecutive years of record highs, mostly due to an 11% drop in fertilizer prices.

Mistakes of the Past—The ’80s

Today’s farm economy looks a lot like the ’80s farm crisis. There are several similarities that have the farm economy pointed in the same direction but there are some big differences and it’s not too late to change for the better.

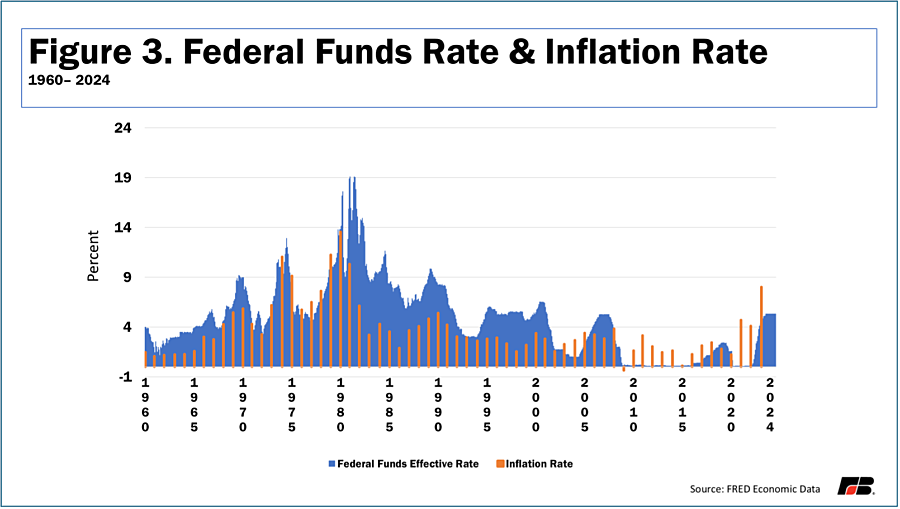

The time between 1964 and 1982 would become what is called “The Great Inflation,” a result of the Federal Reserve’s expansion of the money supply to combat unemployment decades before. In 1973, President Nixon’s secretary of Agriculture responded to a multiyear contract with the Soviet Union for feed grains by calling for American farmers to produce as much as possible and plant “fencerow to fencerow.” Land values increased and lenders were more than happy to provide credit to farmers. By 1980, inflation had risen to 14.5% and unemployment over 7.5%. Prices were sky high when the Fed implemented their policies to combat inflation, increasing the federal funds effective rate. As inflation fell, the real cost of borrowing, including existing loans, took off for all Americans, but hit hardest at the farm families and rural bankers who had made those encouraged production investments. These rate hikes, along with crashing crop prices, caused land values to plummet and were followed by a massive recession.

The 1981 farm bill focused primarily on crop insurance and crop insurance subsidies. It was not able to serve farmers during this time of high inflation. This is a lot like how the recently expired 2018 farm bill wasn’t serving farmers as intended after four years of inflation and rising interest rates. Toward the end of the ’80s, farmers produced a massive crop just in time for a global economic slowdown. Prices crashed, and farmers were left with production losses and less able to use credit because of low income, lower land values and high interest costs (Sound familiar?).

The 1985 farm bill, the Food Security Act, provided more effective commodity price income supports and created several new conservation programs. But for many it was too little, too late. By the end of the ’80s, it is estimated that 300,000 farms had defaulted on loans and more banks had failed than during the Great Depression.

How Today is Different From the ’80s

As in the ’80s, in 2022 the Fed began using interest rate hikes to reduce inflation, moving from 8% down to a target rate of 2%. Due to the large amount of capital needed up front to farm, farmers across the country also rely on credit to help meet cash flow needs. When the Fed increased interest rates, it increased their interest costs by 43% from 2022 to 2023. The Fed’s recent decision to drop interest rates by half a percent will help, but this still leaves minimum interest rates for an operating loan, the kind a farmer would use to plant a crop, at about 8%. While these interest rates are lower than they were in the ’80s, they are the highest in quite some time (Figure 3).

Another difference between now and the ’80s farm crisis is land values. According to USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service’s most recent Land Value Summary report, released on Aug. 2, land values increased to an average of $4,170 per acre in 2024, up 5% from the year before. This is, so far, the opposite of what happened in the ’80s, when land values fell 7.3% between 1980 and 1990. Land value is important for ag lenders because increased land value gives a farmer with land more collateral to borrow against (although it also raises the cost for rented land farmed.) When land values fell in the ’80s it restricted farmers’ ability to get a loan just as prices fell.

Conclusions

The most alarming piece of the current ag economy is lower commodity prices without a farm bill to help sustain our farmers. U.S. farmers have produced a massive crop two years in a row. While this is amazing in terms of productivity and the ability of our farmers to feed the world, it has also caused commodity prices to drop dangerously low. Stocks of stored grain are up, and a record crop without matching demand threatens to put more downward pressure on prices.

On top of that, inflation has driven up costs for inputs, with very few coming down in recent years. Interest rates are elevated due to the Fed’s battle to bring down inflation, driving up the cost of borrowing.

When Congress got around to passing a farm bill in the ’80s, it was too little, too late for many. This is a lesson from the past: that America’s farm families are the ones that will pay for an outdated (or expired) farm bill. The farm economy is at a pivotal moment, if policymakers are not able to learn from the mistakes of the past, the past could repeat itself. The good news is that interest rates have started to come down, and land values have not fallen like they did in the ’80s. It will be critical for interest rates to continue dropping so farmers have access to credit to help weather cash flow issues until an updated farm bill is passed.

Many farmers entered 2024 with strong balance sheets; but expensive credit comes with a price. It may help farmers survive this year, but using credit at higher interest rates depletes working capital. Less working capital and lower crop prices mean that the access to credit could be worse in 2025 and the burden of debt could make many of these same farmers vulnerable.

This Market Intel will be followed by another that will lay out the leadership traits and actions that can help farmers survive the challenges of this farm economy.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL