Egg Prices Continue Setting Records

Bernt Nelson

Economist

Easter and Passover are both just over a month away, and you may be in for a shock when it comes to egg prices as you prepare for these egg-centric holidays – whether it be for an Easter egg hunt or a Seder plate. Egg prices are setting new records in 2025. The combination of inflation and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) has caused egg prices to rise more than 350% per dozen compared to this time last year. In fact, some restaurants are having to raise menu prices just to keep up with the cost of eggs. But what is responsible for this rise in price? This Market Intel will evaluate the two biggest causes of record high-egg prices and how these prices are ultimately driven by big challenges in farm country.

Egg Prices and Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza

Eggs are considered an inelastic good. This means that even when egg prices change, consumers still buy about the same amount of eggs. Unlike other products, in many applications such as baking, eggs don’t have good substitutes. They are also a healthy – and typically the most affordable – source of protein, which makes them desirable even if prices go up. This relatively unchanging demand for eggs means that supply factors can have a big impact on egg prices.

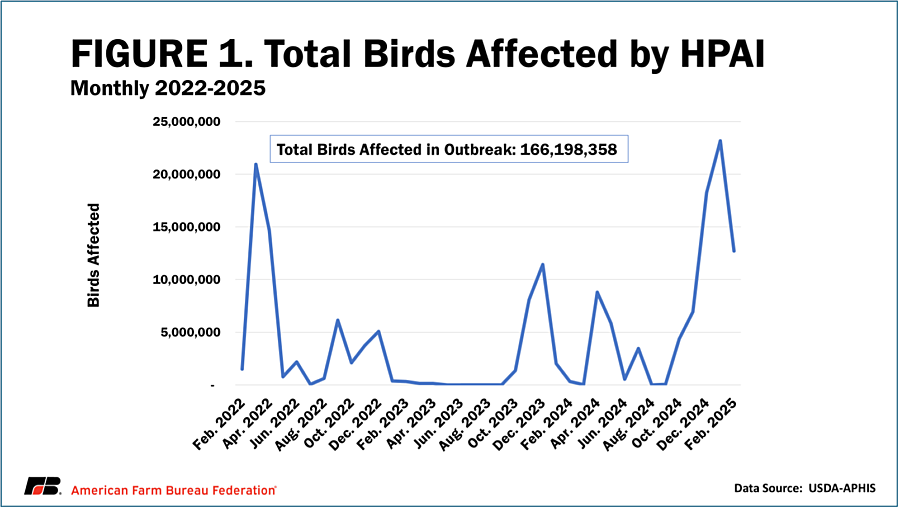

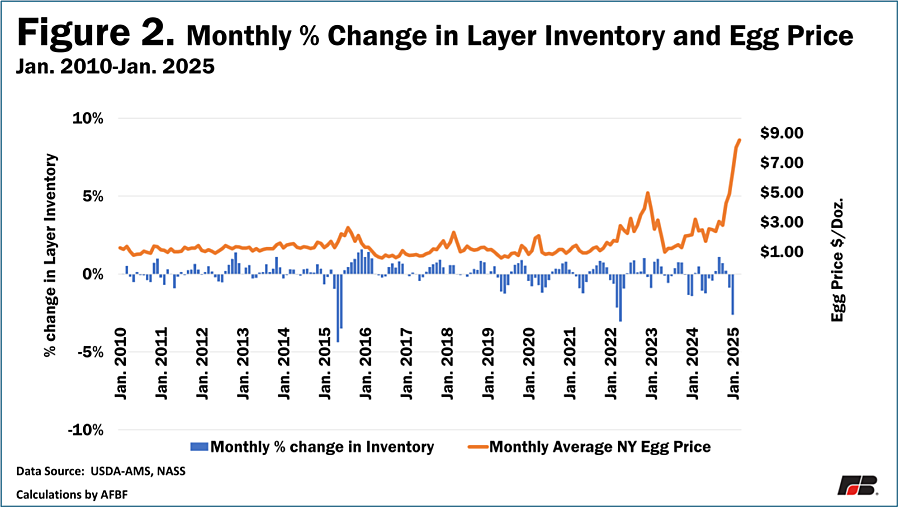

The loss of egg-laying chickens from HPAI is the biggest factor driving up egg prices. Since 2022, HPAI has affected over 166 million birds including 127 million egg layers. That’s an average loss of 42.3 million egg layers per year, or about 11% of the 5-year average annual layer inventory of 383 million hens since the outbreak began. These losses have resulted in reduced egg supplies and record egg prices. According to USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS), the monthly national average price for large Grade A eggs in January was a record-high $4.95 per dozen. Some 12 million birds, mostly layers, were lost in February, bringing the total number of birds affected so far in 2025 to over 35 million and driving egg prices even higher. The daily national average price for a dozen large eggs was $8.15 per dozen on March 4, 2025.

This outbreak has been different than the 2014-2015 outbreak. In 2015, the virus came on strong and basically disappeared after a year affecting over 50 million birds. In past outbreaks of Avian Influenza, we’ve seen hot weather kill off the virus. Instead of disappearing when the seasons change, the virus has continued to circulate in wild birds as well as our nation’s poultry flock. Another difference between the current outbreak and the one that occurred in 2015 is there are a lot more backyard flocks in the U.S. compared to 2015. This means more birds that are vulnerable to getting the virus, and more opportunities for the virus to spread along the flyways where migratory birds travel.

Remarkable Resilience

According to USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service’s (NASS) annual Chickens and Eggs Summary, the average inventory of U.S. egg-laying hens was 375 million, down 14 million, or 3.5% from 389 million hens prior to the 2022 outbreak of HPAI. In 2024, table egg production was about 93.1 billion eggs, down 2.5 billion eggs or 2.6% from 2021. The industry at all levels has shown remarkable resilience in keeping eggs on grocery store shelves and providing an essential protein source to American consumers. Since 2022, egg farmers have lost on average 11% of the laying flock every year due to HPAI, yet they astonishingly managed to keep the annual average layer flock size just 3.5% below pre-outbreak levels.

Egg Prices and the Farmer

Higher prices for eggs do not mean farmers are getting rich. On the contrary, these prices are a result of the farmer’s loss of millions of birds to disease. USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) does have an indemnity program that provides compensation to the grower or owner for infected or exposed poultry and eggs that are destroyed to control HPAI. However, it can take up to a year for a farm to complete cleaning and raise new chicks to egg-laying age. This indemnity does not cover costs during the time the farm goes without income. On top of the economic loss, the death of an entire flock, sometimes millions of birds, from avian influenza is a traumatic experience for farm families.

The United States’ primary control and eradication strategy for HPAI in domestic poultry, as defined by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), is de-population. When HPAI is detected, the entire flock is de-populated, for several reasons. When HPAI is present in even one bird in a poultry house or barn, it typically spreads through the whole facility. Another reason is to prevent spillover into other houses on the premises or wild birds that could spread the virus which also leads to a greater risk for mutation. Research has shown that de-population is the most humane and effective method of control. HPAI affects multiple organs in birds with a mortality rate near 100%. This is a higher mortality rate than the Ebola virus in humans.

Inflation and Cost of Production

Inflation is another, if less dramatic, factor driving up egg prices. While inflation has slowed over the last couple of years, it’s important to remember inflation is a measure of growth. Slowing inflation doesn’t mean prices are going down, it means they are getting expensive more slowly. According to Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS), the unadjusted Consumer Price Index (CPI) for all items for urban consumers rose 0.5% in January bringing CPI inflation for the year to 3%. The unadjusted 12-month CPI for eggs contributed to this, rising 53% from Jan. 2024 to Jan. 2025. Shorter term, the CPI for eggs was up 13.8% in just two months, from Dec. 2024 to Jan. 2025.

Inflation does more than drive up the price of eggs in the grocery store, it also raises the cost of everything it takes to produce eggs on the farm and get them on grocery store shelves. According to USDA’s latest farm income forecast estimates, total farm production expenses fell by 0.6%. Despite this drop, production costsfor expenses like labor wages, interest and fuel are still historically high following price spikes in 2022 and 2023. USDA NASS’s Prices Paid by Farm Type Index for Livestock Farms increased by 36% from Jan. 2020 to Jan. 2025. Even with higher prices for eggs, input costs and the added risk from HPAI makes being an egg farmer a risky business.

Another elevated supply cost for egg farmers is the price of chicks. Chicks that go on to become egg-laying hens cost more to replace than chicks that are used for meat production, which are called broilers. However, flocks used to provide eggs for laying hens are susceptible to avian influenza just like any other birds. Both sides of poultry production—egg layers and broilers—are suffering from increased replacement costs due to HPAI.

Summary

The two biggest factors driving egg prices to record levels are HPAI and inflation. HPAI is continuing to cause problems for poultry and egg farmers across the country with over 166 million birds affected since the outbreak began. Even though egg prices are at record levels, farmers are not getting rich. Expenses remain historically high, and farmers are continuing to fight through the risk of losing their flock to this devastating disease.

This Market Intel will be followed by another that dives into the biology and science of potential strategies for mitigating HPAI.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL