Estate Taxes Are A Threat to Family Farms

TOPICS

Estate TaxVice President of Public Policy and Economic Analysis

Patricia Wolff

Senior Director, Congressional Relations

John Newton, Ph.D.

Vice President of Public Policy and Economic Analysis

Patricia Wolff

Senior Director, Congressional Relations

Estate taxes are a tax on the transfer of property following a death. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act included an estate tax exemption, which expires in 2025, that requires an estate to file and pay taxes when gross assets exceed $11.58 million per person. After Dec. 31, 2025, the exemption amount returns to $5 million per individual adjusted for inflation, as set by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. Previously the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 had gradually raised the exemption amount from $675,000 to $3.5 million in 2009.

Farms with assets above the estate tax exemption often must liquidate some of those assets to meet estate tax obligations, which can reach as high as 40% of the taxable amount. Estate taxes are a particular concern for farmers and ranchers because they are based on the market value of the asset; given the consistent appreciation in agricultural land and assets, this can be very high for farm and ranch families. A limitation on the estate tax exemption means that each year, fewer and fewer farm families will be protected from the estate tax– a clear risk to the continuity of family farms.

A recent study by USDA’s Economic Research Service (America’s Diverse Family Farms: 2019 Edition) indicated that, as of 2018, 98% of the 2-plus million farms in the U.S. were family farm operations. To preserve these family farm operations, serious consideration should be given to eliminating estate taxes or at the very least making permanent the current inflation-adjusted TCJA estate tax exemption. By eliminating estate taxes, or making the current exemptions permanent, U.S. farmers and ranchers will be able to avoid, at least partially, liquidating inherited farm assets to meet the death tax’s financial obligations.

Moreover, to prevent mass liquidation of farmland and farm assets, significantly reducing the estate tax exemption to increase tax revenues and offset other government spending – or for any other reason – should be avoided. Today’s article uses USDA’s 2020 Land Values Summary and data from the 2017 Census of Agriculture to review the acreage needed to reach the estate tax limit as well as the number of farms and farmland acreage that would be impacted by estate taxes at current and potential estate tax exemption levels. A recent Market Intel analysis reviewed 2020 agricultural cropland and farmland values, i.e., No Change in Land Values For 2020.

National Estate Tax Implications

During 2020, the national average value of farm real estate, including all land and buildings on farms, was $3,160 per acre, unchanged from 2019’s record high. Based on this, it would take approximately 3,700 acres to reach the current $11.58 million estate tax exemption.

Importantly, over the last decade, the value of farmland in the U.S. has increased by nearly 50%, or $1,010 per acre. Given that increase, it would take 32% fewer acres to reach the estate tax exemption level in 2020 than it would have in 2010.

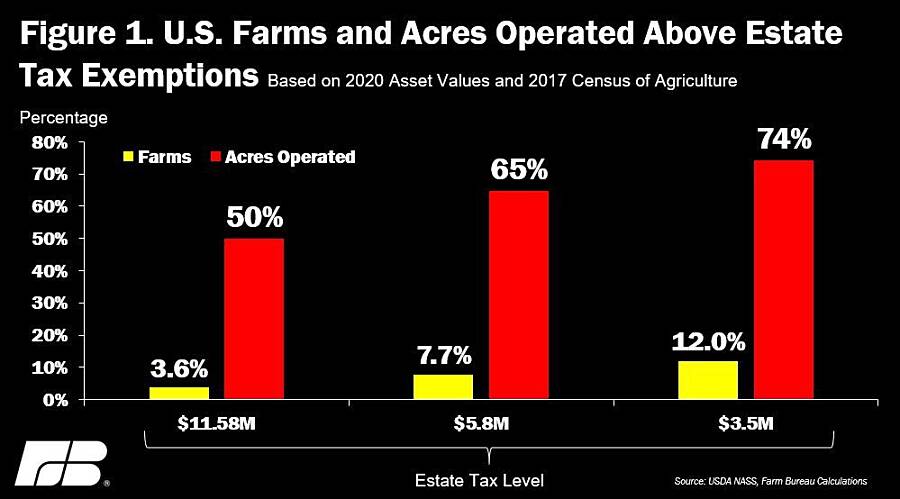

Based on the most recent Census of Agriculture, more than 74,000 family farmers were operating 2,000 or more acres in 2017, suggesting that approximately 3.6% of the more than 2 million family farms could potentially have farm assets that exceed the estate tax exemption. These 74,000 farms operate more than 449 million acres, indicating that nearly 50% of the farmland in the U.S. could face increased liquidation pressure upon the transfer of assets at death.

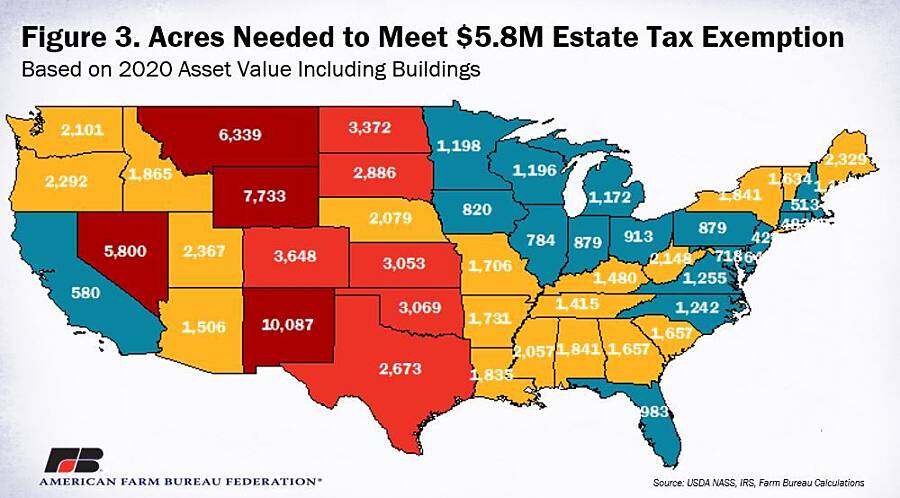

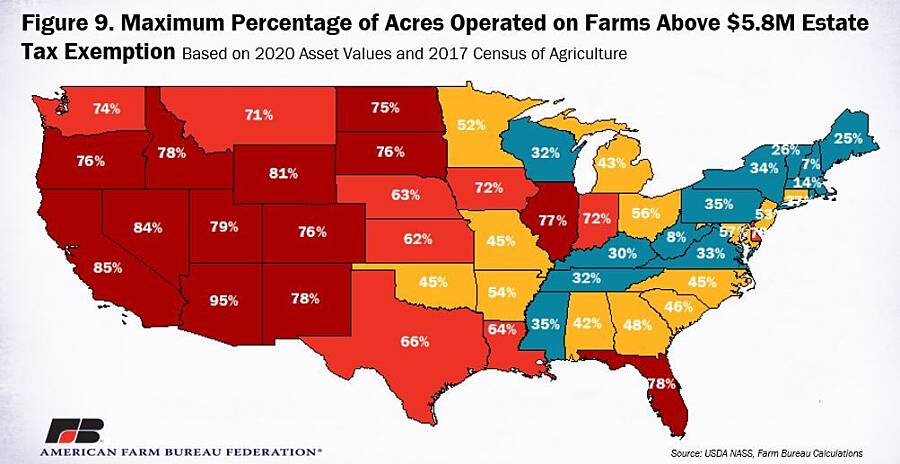

Realizing that on average 15% of total farm assets come from assets other than real estate such as farm machinery or livestock, these numbers actually understate the number of family farms that could have assets that exceed the estate tax exemption. If the current $11.5 million estate tax exemption level is not made permanent, in 2026 the estate exemption would fall to an inflation-adjusted $5 million. In 2020 dollars, the $5 million exemption level would be approximately $5.8 million, pushing the threshold for triggering the estate tax down to approximately 1,800 acres. When evaluating this threshold on a state-by-state level, more than 156,000 farms, or nearly 8% of farms would be impacted. These farms account for more than 582 million acres, indicating that as much as 65% of farmland could be operated by farms above the inflation-adjusted $5 million estate exemption level.

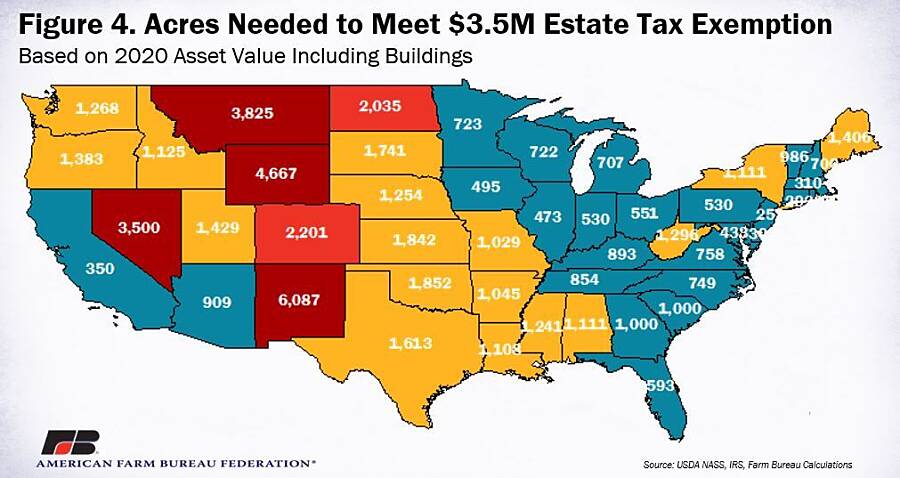

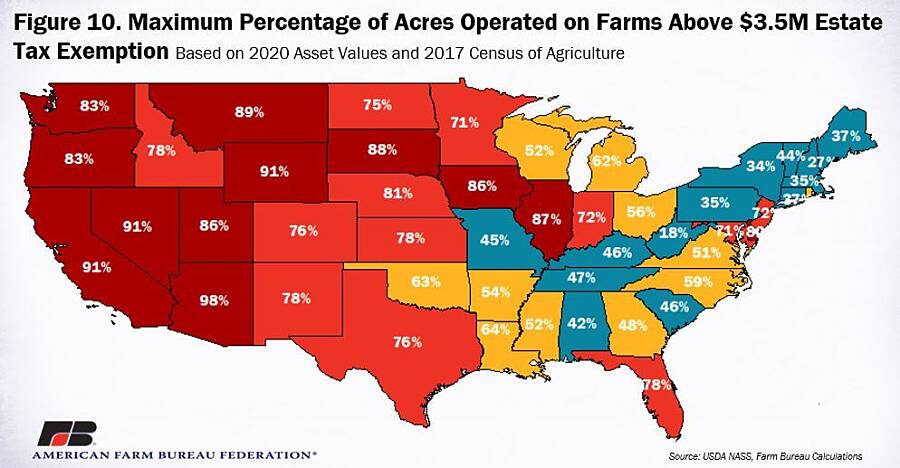

If the estate tax exemption were reduced to $3.5 million, it would require slightly more than 1,100 acres to reach the exemption level. Based on state-level data, more than 243,000 farms, or 12% of operations nationally, would be impacted. These farms operate a total of 667 million aces, suggesting that a $3.5 million estate tax exemption could impact as much as 74% of the farmland in the U.S. Figure 1 highlights the percentage of farms and percentage of farmland operated that could be subject to estate taxes at various estate tax exemption levels.

State-Level Estate Tax Implications

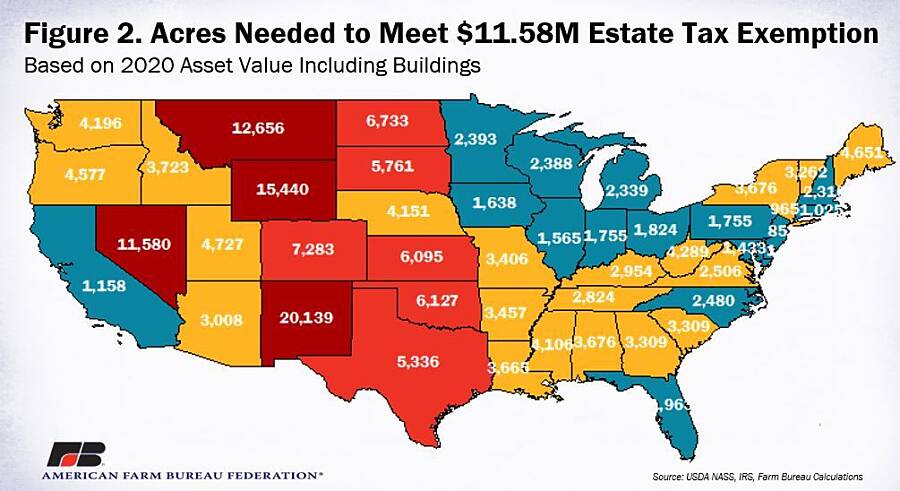

At the state level, the impact of the estate tax limitations will vary based on the average farmland value and the average farm size. For example, states with higher average farmland values, such as Illinois and Iowa in the Corn Belt, are more likely to reach estate tax exemption levels on smaller farm operations. Meanwhile, Western states with larger family farm operations are more likely to be impacted by estate taxes, despite having lower average farmland values. As the exemption falls, it takes fewer acres to reach the estate tax exemption level. Figures 2 through 4 highlight the farmland acres needed for a farm operation to meet the current and potential estate tax exemption levels.

Percent of Farms Impacted

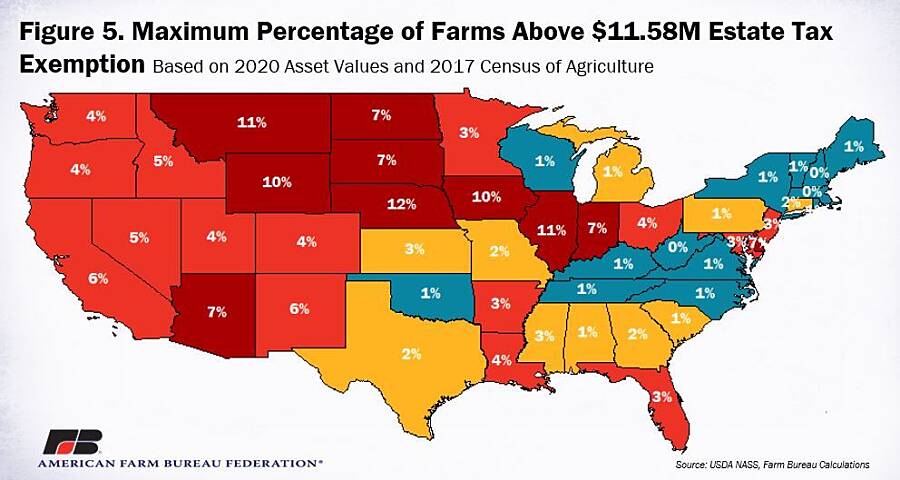

While at the national level the current estate tax exemption would impact approximately 4% of U.S. family farms, at the state-level the percentage of farm operations potentially impacted varies significantly. For example, at $11.58 million, as many as 12% of Nebraska farms and 11% of both Illinois and Montana farms operate enough acres to be above the estate tax threshold, Figure 5. This is due to larger farm operations in Montana and higher farmland values across the Corn Belt. In the Northeast, despite higher average farmland values, fewer farms are impacted by the estate tax exemptions as those farms typically operate fewer acres.

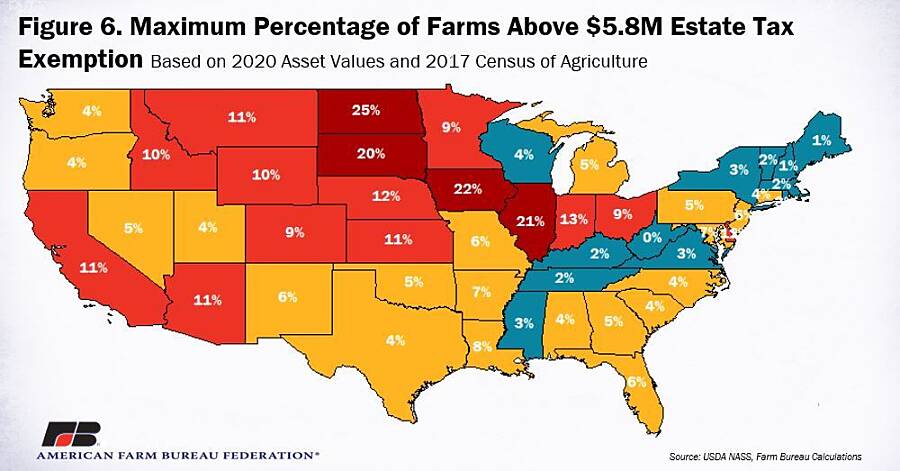

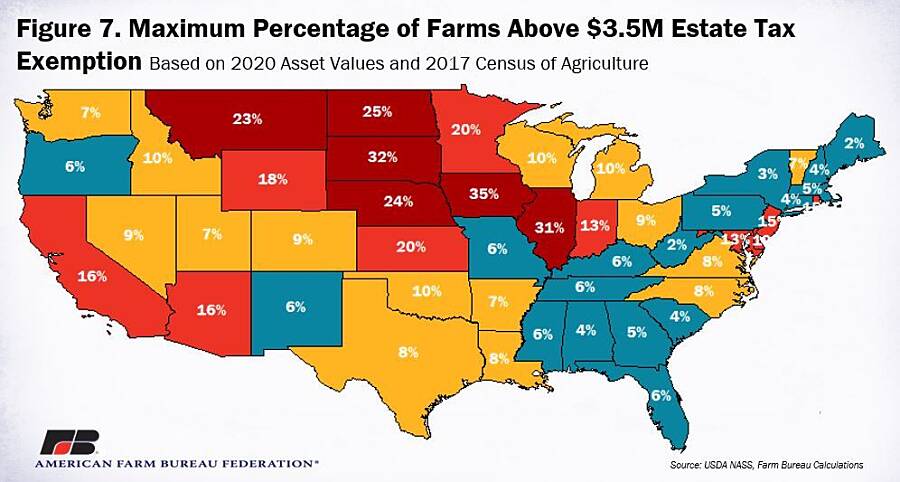

Should the current exemption expire in 2026, and revert back to the inflation-adjusted $5 million, more than 20% of farm operations across Illinois, Iowa and North and South Dakota would likely operate acres above the estate tax thresholds, Figure 6. If the exemption were reduced to $3.5 million, as many as 30% of farm operations in states such as Illinois, Iowa and South Dakota could be above the estate tax exemption, Figure 7.

Percent of Acreage Impacted

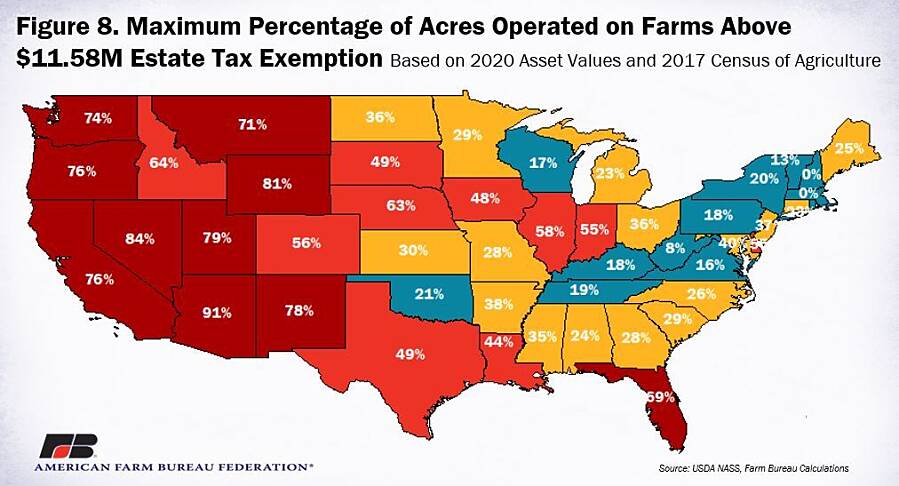

At the national level, approximately 4% of family farms operate 2,000 acres or more and represent approximately 50% of the farmland operated. It follows then that the estate tax exemption and potential reductions in the exemption to as little as $3.5 million would disproportionately impact larger family farm operations, especially those operating highly productive agricultural land.

Across the U.S., the percentage of farmland operated by farms potentially above the estate tax threshold of $11.58 million range is above 50% across much of the Corn Belt and is more than 70% in many Western states. In Western states, families tend to operate larger farm operations, and despite lower average farmland values, more of the farms and most of the acreage in the state would be subject to estate taxes when the property is transferred following death. In these areas, the largest family farms would be more likely to have to liquidate assets to meet their estate tax obligations, Figure 8.

Should the $11.58 million estate tax exemption expire, the $5.8 million estate tax exemption would potentially impact operations owning more than 70% of farmland across most of the Corn Belt and 70% to 95% of farmland operated in Western states, Figure 9. At a $3.5 million estate tax exemption, 72% to 86% of acres operated by farms over the exemption in the I-state corridor could be subject to estate tax obligations. In some Western states, more than 90% of the acres operated for the production of high-value specialty crops, dairy and tree-nuts could be impacted by estate tax provisions, Figure 10.

Summary

The U.S. food and agricultural sectors are responsible for roughly one-fifth of the country’s economic activity, directly supporting over 23 million jobs – representing nearly 15% of U.S. employment (Feeding The Economy).

The death tax’s threat to family farms and the agribusinesses and rural economies that rely on them is clear. Farming and ranching is capital-intensive; yet farmland, cropland, buildings and machinery are highly illiquid assets. As a result, family farms have few options to generate cash to pay the estate tax. When estate taxes on an agricultural business exceed cash and other liquid assets, surviving family partners may be forced to sell land, buildings or equipment needed to keep their businesses running.

The current estate tax exemption of $11.58 million is set to expire at the end of 2025, dropping the exemption down to $5.8 million in 2026. It’s also possible congressional lawmakers will try to further reduce the exemption, making it even more difficult for family farms to survive the death of a loved one. Additionally, farmers and ranchers could be forced to slow business expansion if they want to preserve their land for future generations. This may result in sub-optimal business decisions that negatively impact the family farm as well as the rural communities, businesses and jobs they support.

Given the demographics in agriculture, it’s critical that Congress eliminates the death tax -- or at the very least make the current $11.6 million exemption permanent so that family farms across the country can continue their agricultural legacy.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL