Grasshoppers Eating into Western Farmers’ and Ranchers’ Bottom Lines

TOPICS

grasshopper

Daniel Munch

Economist

When learning U.S. history, narratives of vast swarms of locusts ravaging millions of acres of farmland are often recounted. Not all grasshoppers are locusts, and the swarms aren’t quite as big as they were in the 1800s, but grasshoppers and Mormon crickets remain a persistent risk to agriculture, inflicting significant damage to rangeland and crops. This article provides an overview of these insects’ economic impact on agriculture in the West and efforts to manage and mitigate their populations.

Background

Almost 400 native species of grasshoppers inhabit the Western United States, though only a small fraction (about 12 species) are considered pests. Grasshoppers compete with cattle and other herbivores (including wildlife like deer and elk) for forage and are more likely to become a threat in areas with less than 30 inches of rainfall annually. They can consume up to 50% of their body weight each day in forage (while cattle consume 1.5-2.5% of their body weight). Put differently, just 30 pounds of grasshoppers will eat as much as a 600-pound steer in a day. Grasshoppers are an even bigger menace to crop farmers and ranchers on public and private lands when drought conditions are added to the mix.

Most species of grasshoppers and Mormon crickets produce one generation each year and go through a three-stage life cycle – egg, nymph and adult. In most cases, eggs are deposited in soil in “pods” that contain eight to 30 eggs in late summer or fall. The eggs pause development over winter and resume in spring. Depending on soil temperature – warmer temperatures speed up this process greatly – eggs hatch sometime in the spring. Once hatched, the nymphs begin feeding within a day. During this portion of their life grasshoppers are most susceptible to the impacts of weather, disease and parasites. Nymphs become adults within 40-55 days of hatching. These lifecycle characteristics are important for predicting possible population booms (depending on weather), as well as effective management techniques.

Grasshopper and cricket outbreaks not only result in the physical destruction of forage and crops but also contribute to soil erosion and degradation, disrupt rangeland nutrient cycles, and impede rangeland water filtration, which can have lasting impacts on rangeland ecosystems. Western landowners face heightened risks from grasshoppers due to the substantial amount of federally owned land in the region. Pest infestations on federal lands reduce the quantity and quality of forage available for those with public lands grazing leases. In the absence of grasshopper and cricket management on federal lands, insects can migrate onto private lands, undermining the effectiveness of common private pest management efforts. This movement from public to private lands complicates the control of these pests.

Population Densities

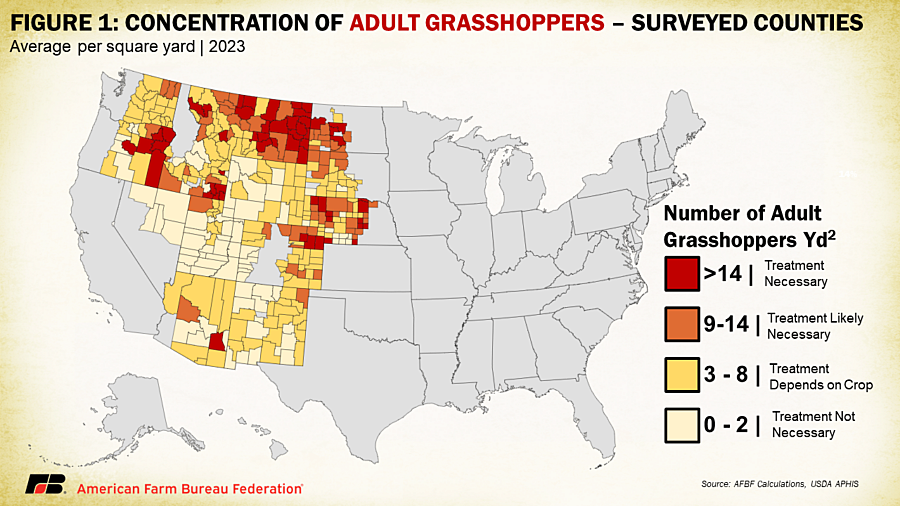

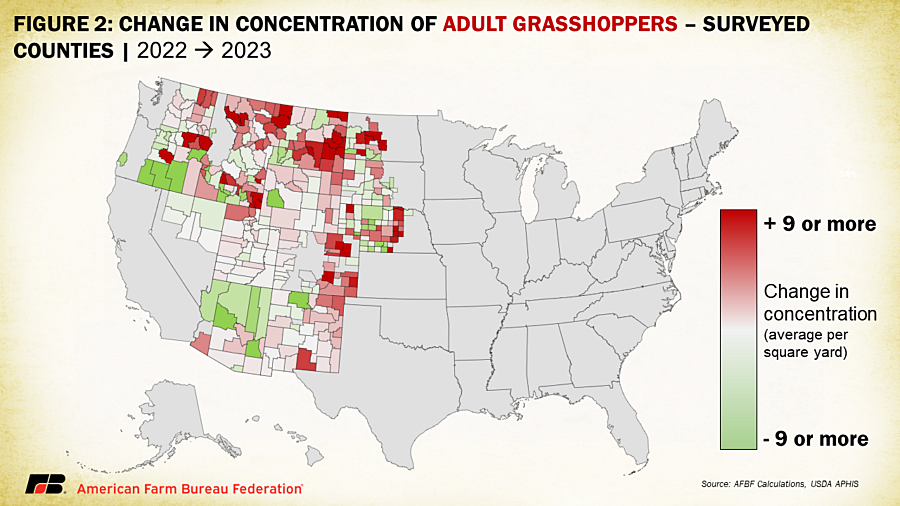

Through the Plant Protection Act of 2000, USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has the congressional mandate to control grasshoppers on rangelands via the Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program. One important step of this process is monitoring nymph and adult populations of grasshoppers and Mormon crickets through surveying. The square yard method establishes an average quantity of nymph and adult insects per yard over about 30 samples per county. Figure 1 displays the population densities of adult grasshoppers in counties with APHIS surveys in 2023. Numerous counties and states not surveyed, including California, Kansas and Oklahoma, have significant grasshopper populations so these graphics should be used as a baseline. Figure 2 shows the difference in per yard populations from counties with surveys between 2022 and 2023. Almost 10% of surveyed counties (34 out of 355) experienced adult grasshopper population increases of 9 or more per square yard – an increase within the threshold for pest treatment. A decrease in grasshopper populations between years may be linked to many factors including increased precipitation, stronger disease pressure or successful treatment efforts, while an increase may be a result of the opposite.

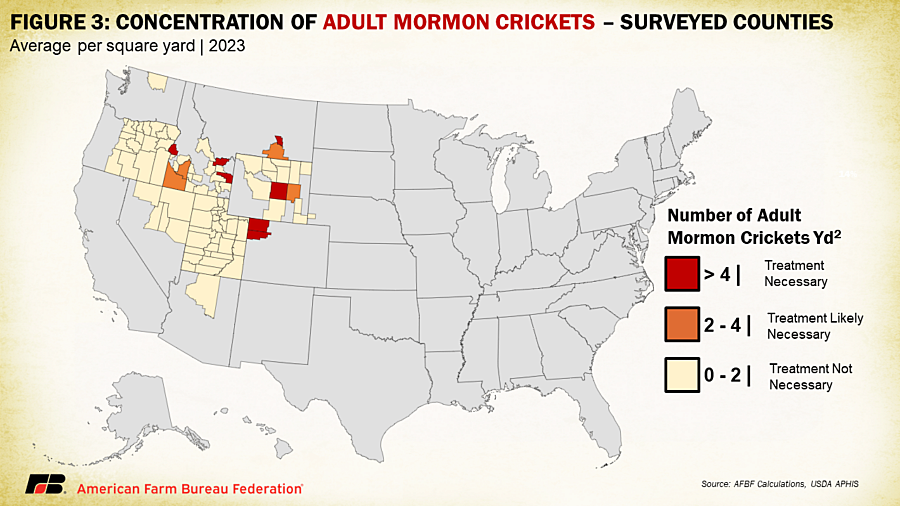

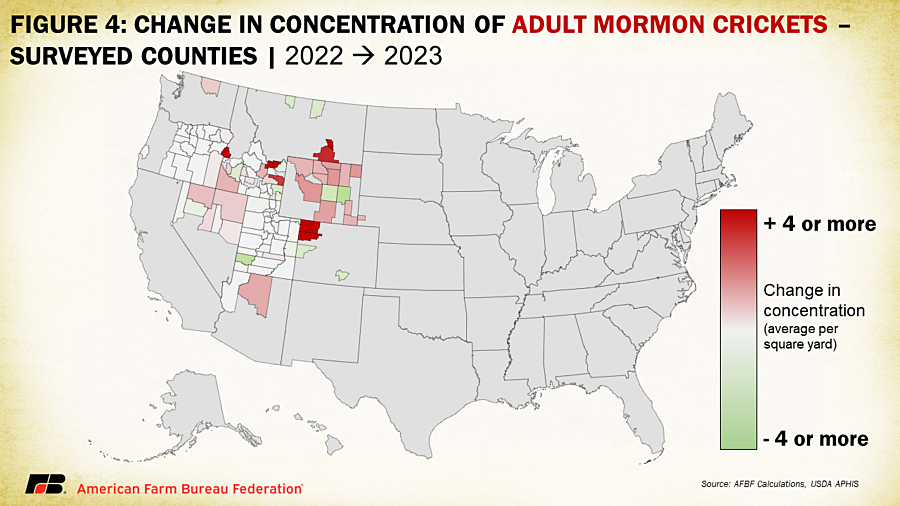

Figures 3 and 4 replicate figures 1 and 2 but for adult Mormon crickets instead of grasshoppers. Mormon crickets are a flightless type of katydid that walk or jump in groups of millions or billions of individual crickets and can migrate great distances. The Mormon cricket is the only katydid species known to reach outbreak level populations in the United States and, like grasshoppers, damage grasses and other crops through consumption. They’re also a large nuisance in rural communities where they blanket roads, homes and sidewalks.

Economic Impact

Literature on current economic impacts of grasshoppers on agriculture is limited. Generally, monetary losses either fall under the value of crops or rangeland consumed by insects that could no longer be sold on the market or consumed by ruminants to produce meat or wool and the cost to treat populations that have reached pest-concern levels. Speaking to the former, county-level estimates of grasshopper damage to crops and rangeland are available in some states. For example, 2023 California County Agricultural Commissioner Disaster Reports are available (by request) from several impacted northern counties in the state (Siskiyou, Modoc and Plumas). These forms are used when requesting a USDA secretarial disaster declaration and list the crops damaged, yield losses and corresponding dollar losses from available pricing information.

In Modoc County alone, ag commissioner estimations indicated over $52 million in crop and rangeland losses due to severe grasshopper infestations in 2023. This included $16 million in damage to alfalfa, which had a yield decrease from 6.4 tons per acre to 4.48 tons per acre (-30%) across 7,280 of Modoc’s 36,400 planted alfalfa acres (20% of acreage impacted). On 180,000 acres of rangeland, which usually supports 2 animal unit months (AUMs) per acre, only 0.6 AUMs per acre were supported, resulting in an estimated loss of over $10 million in forage value. An AUM is the amount of forage needed to sustain one cow and her calf or one horse, or five sheep or goats for a month. Modoc County estimations also included $15 million in grain hay yield losses, $6 million in lost pasture forage value, $2 million in small grain yield losses and $1.8 million in other hay yield losses. In Siskiyou County, conservative estimates of crop and forage yield losses exceeded $32 million and in Plumas County they were over $1 million.

The impact of grasshoppers on crop and forage yields will vary widely by location and depend on factors including weather conditions, vegetation densities and types and altitude. Recognizing these differences, one crude method to estimate a baseline economic impact number of grasshopper infestations across the West is to extrapolate average yield losses and affected acreage values observed in the described California counties to other infested counties. Focusing on a single crop type and selecting counties with over three adult grasshoppers per yard (where treatment may be necessary depending on the crop) reduces the risk of overestimating actual losses since many crop and forage types are affected by grasshopper infestations.

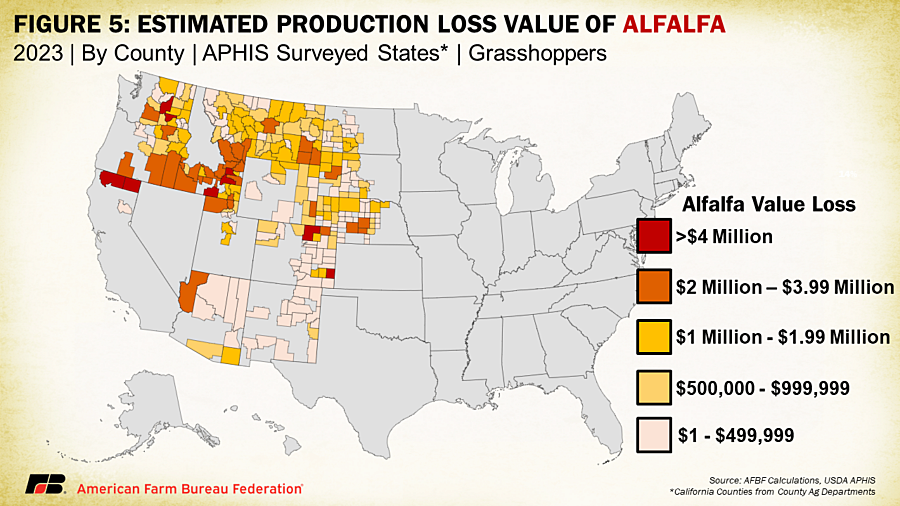

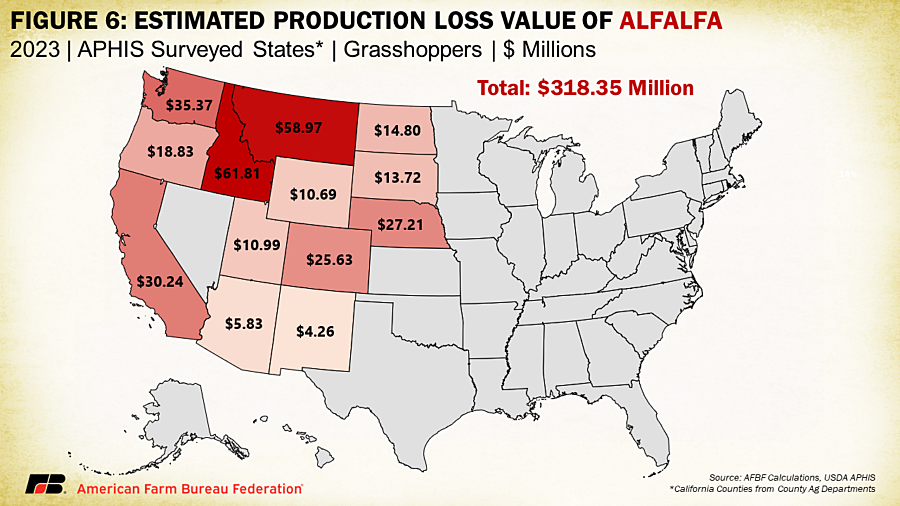

Following this approach, alfalfa, having been impacted in all reported California counties and commonly grown in the West adjacent to or near federal lands, was selected as the crop to analyze. Adjusting for yield loss and acreage impacted gives an average total county production loss of 6%. Utilizing data from the 2022 Census of Agriculture, county-level survey data on alfalfa production, and total sales value by state, we calculated the difference in production value per county, assuming a 6% increase in production in the absence of grasshopper infestations. Figure 5 displays the per-county estimations of lost alfalfa values using this approach and Figure 6, the total combined per-state values. In total, conservative estimates put production value losses in 2023 due to grasshopper infestations at $318 million. This represents a baseline number with true impacts likely hundreds of millions of dollars higher. Losses of this magnitude are detrimental to operations already operating on small and often negative margins and reveal the true threat of these insects on farmers’ and ranchers’ livelihoods.

Another way to pinpoint some grasshopper damages is through Risk Management Agency indemnity data that shows payments made on crop insurance policies triggered from an insect-related cause of loss. In Montana, for instance, there were $7.7 million in indemnity payments made for crops lost to insects in 2023. This includes over $5 million in wheat, more than $1.6 million in dry peas and $439,725 in barley. All counties with reported insect-related indemnity payments had significant densities of grasshoppers reported by APHIS surveys, though some of these payments could have been for other pest types.

Treatment

The Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program offers treatments for federal, state and private rangelands through a cost-share model within APHIS. Under this program, when funding is available:

- APHIS covers 100% of the treatment costs on federal and tribal rangelands.

- On state lands, APHIS provides 50% of the funds for treatment and control, with the state covering the remaining 50%.

- For private rangelands, APHIS contributes 33.3% of the funding, while the state and private landowner share the remaining costs.

It's important to note that APHIS is unable to conduct suppression programs for grasshoppers and Mormon crickets on private croplands. However, they do perform rangeland suppression treatments in areas where federally managed rangeland is directly adjacent to private croplands.

Before APHIS treats for grasshoppers or Mormon crickets on rangelands, two things need to happen. First, APHIS must receive a written request from the landowner or manager for treatment, and second, APHIS must determine that the treatment will effectively suppress grasshopper and Mormon cricket populations to levels that will not cause significant forage loss and ecological damage. When a written request is made, APHIS visits the site and assesses certain factors to determine if treatment is necessary. Part of this process is the population density surveying described earlier and reviewing treatment options and costs. If funding is available, a written request has been received and treatment is deemed necessary, a treatment plan will be submitted for bids by pest control contractors. APHIS will select a contractor for each treatment. There may be limited contractors offering grasshopper treatment services, leading to reduced competition and potentially higher treatment costs.

APHIS may apply insecticides using several different methods. Using ground equipment by distributing baits usually made out of wheat bran or rolled oats and carbaryl or aerially by spraying ultra-low-volume applications on treated acres. Most commonly, APHIS uses a method of integrated pest management for grasshoppers and crickets called reduced area and agent treatments to limit costs and insecticide use. This approach divides treated acres into a patchwork of treated swaths and untreated swaths. Insects in treated acres are killed directly and insects in untreated area are killed as they move between untreated and treated swaths. This approach reduces the cost of control by more than 50% and provides 80%-95% protection. Insecticides utilized by APHIS include carbaryl, diflubenzuron and malathion. Diflubenzuron is most commonly used because its risk to non-target terrestrial species and aquatic life is low and its effectiveness as an insect growth inhibitor is high. All insecticides are currently registered for use and labeled by the Environmental Protection Agency for rangeland control of grasshoppers. Each pesticide used is effective and safe when used under the right conditions in accordance with label requirements.

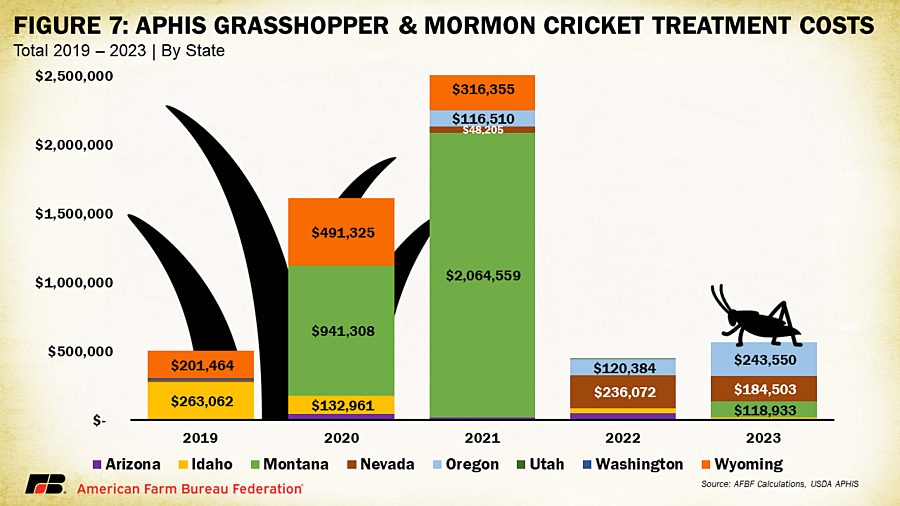

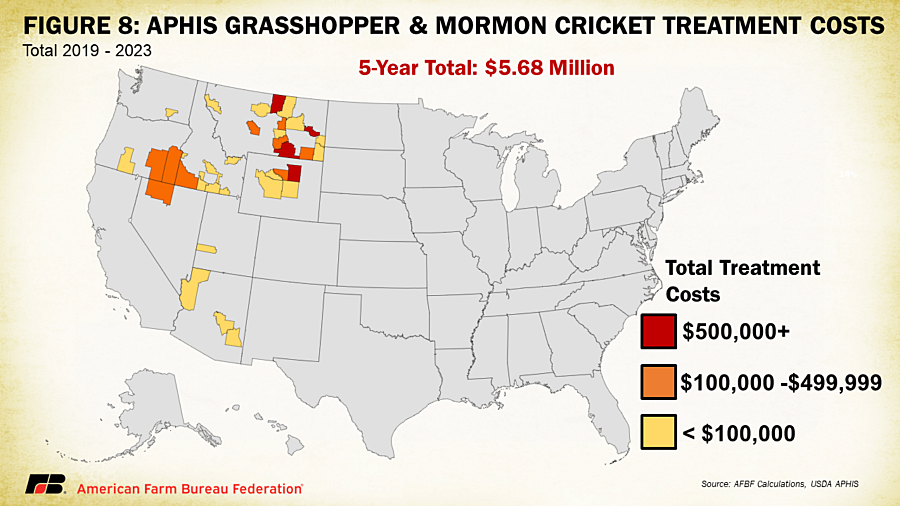

Between 2019 and 2023 APHIS protected over 3.33 million acres across eight Western states, with 2.8 million acres treated for grasshopper control and 482,000 acres treated for Mormon crickets. This has corresponded to $5.68 million in program treatment expenditures over the five-year span ($4.6 million for grasshopper control and $1.07 million for Mormon crickets). Figure 7 displays APHIS grasshopper and Mormon cricket treatment expenditures by year and by state. Data on whether treatments were on federal, state or private acres is not available, so the cost paid by states and/or landowners is not known. Nearly 70% ($3.13 million) of treatment costs were spent in Montana, primarily in 2021 when over $2 million was spent across 10 counties. Mormon cricket control costs have been split primarily between Nevada ($482,000) and Idaho ($423,000), with most of the remainder in Oregon ($157,000). Figures 7 and 8 display the counties where APHIS treatments occurred between 2019 and 2023.

Summary

Even in the 21st century, outbreaks of grasshoppers and Mormon crickets pose a threat to Western U.S. agriculture. The economic impact of these insects on rangeland and crops remains significant, with millions of dollars in losses reported annually across affected counties. This analysis only scratches the surface in terms of total economic damages due to the limited data available and isolated surveying. Efforts to manage and mitigate grasshopper populations, led by APHIS through the Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program, involve sophisticated monitoring and targeted treatments. Continued coordination and efforts among the federal government, states and private landowners is essential to safeguarding the livelihoods of farmers and ranchers against these small but hungry pests.