Overview of Title II Conservation Programs in the Farm Bill

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Mike Tomko

Shelby Myers

Former AFBF Economist

First incorporated into a farm bill in 1985, the conservation title is what some would consider the original Green New Deal. Its voluntary conservation initiatives give farmers and ranchers flexibility to adopt practices in a market-based approach.

Farmers and ranchers have always been good stewards of water and land, but the 2018 farm bill, called the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, expanded conservation programs designed to help farmers and ranchers improve water quality and wildlife habitats and populations, protect natural resources and provide many other benefits to surrounding ecosystems. Of the $867 billion of mandatory funding required for farm bill programs over 10 years, $60 billion is allocated for the conservation title of the farm bill, equal to 7% of the bill’s total projected mandatory spending in that timeframe.

The three main programs that make up the conservation title cover working lands and land retirement initiatives. The 2014 farm bill revolutionized conservation programs, consolidating 23 programs into 13 for ease of use and access for farmers and ranchers. The largest land retirement program is the Conservation Reserve Program, with outlays close to $2 billion per fiscal year. The two largest working lands programs are the Environmental Quality Incentives Program and the Conservation Stewardship Program, with a combined dedicated $25 billion over 10 years. Funding for CSP was shifted away from an acreage limitation to limits based on funding. EQIP was expanded and reauthorized with increased funding levels.

History of Conservation Programs

Conservation programs are intended to help share the costs farmers would bear through the implementation or improvement of conservation practices on a farm or ranch. The goal is to help producers with practices that improve soil quality, water quality, air quality and wildlife habitat and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

United States conservation programs are among the oldest in the world. Conservation programs were included in the first farm bill through the Natural Resources Conservation Service, formerly known as the Soil Conservation Service. Enacted in 1935 through the Soil Conservation Act, conservation programs supported farmers in their efforts to preserve the country’s natural resources. Early on, technical assistance was the primary offering, until 1954 when project-based assistance became the norm across the United States to conserve resources and rehabilitate depleted sources. The turning point for conservation practices came during the farm crisis in the 1980s with the creation of the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). The launch of CRP, in addition to other programs, placed a greater emphasis on conservation.

Conservation programs represent 7% of the $428 billion 2018 farm bill over the 2019-2023 period, which is about $29.96 billion over the bill’s five-year life span.

Programs in Title II: Conservation

Conservation Reserve Program, A Land Retirement Program

The Conservation Reserve Program was first introduced in the 1985 farm bill as a way to set aside highly erodible land not suited as prime farmland. Under a CRP contract between the U.S. government and a producer, the producer agrees to take land out of agricultural production for 10 to 15 years. A large majority of CRP contracts enroll whole fields or whole farms, but recently, there has been increased interest in enrolling high-priority, partial-field practices like filter strips and grass waterways. CRP is considered a land retirement program as enrolled acres are retired from farm production for the life of the contract. There is a competitive general sign-up period at select times as well as a continuous sign-up option that is less competitive but only offered to those who qualify.

CRP provides financial compensation via a cash rental rate that is based on the relative productivity of soils within each county and the average cash rent of the county according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) to landowners who voluntarily enroll highly erodible and environmentally sensitive lands. With that, more productive ground remains in agricultural production, while resource-conserving and wildlife habitat preservation practices are installed on marginal acres. In addition to CRP, there are four other land retirement programs in which CRP acres can be enrolled including the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, Farmable Wetlands Program, CLEAR30 and the piloted Soil Health Income Protection Program.

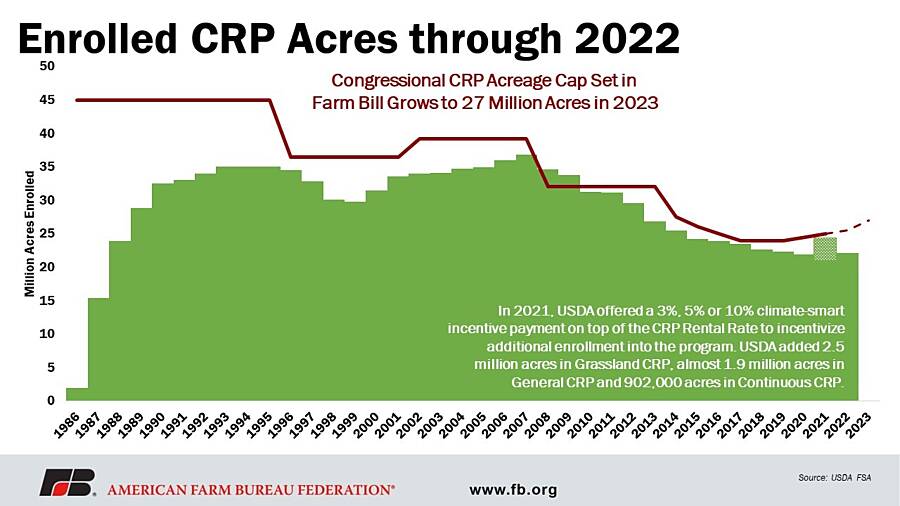

The 2014 farm bill implemented a “step down” policy for the acreage cap allowed in CRP over the five-year life of the 2014 farm bill, reducing acreage from 27.5 million acres in fiscal year 2014 to 24 million acres by fiscal year 2018. In contrast, the 2018 farm bill was a “step up” policy for the CRP acreage cap, moving from 24 million acres in fiscal year 2019 to 27 million acres by fiscal year 2023. For fiscal year 2019, CRP enrollment was capped at 24 million acres; 24.5 million acres in fiscal year 2020; 25 million acres in fiscal year 2021; 25.5 million acres in fiscal year 2022; and 27 million acres in fiscal year 2023.

While the enrollment limits are increasing, actual acreage enrolled has gone in the opposite direction. In fact, until recently, the total number of acres enrolled in CRP has declined every year since fiscal year 2007, as shown in the figure below. CRP enrollment for 2019 was 22.32 million acres and 21.92 million acres for 2020. 2021 enrollment was first reported to be 20.8 million acres, a little more than 4 million acres below the 25-million-acre cap. However, USDA made the decision in 2021 to reopen CRP enrollment to add up to 4 million new acres to the program using a 3%, 5% or 10% climate-smart incentive payment on top of the CRP rental rate. These increased rental rate payments were tied to soil productivity and included additional incentives to implement climate-smart practices on CRP acres. The department also expanded the number of incentivized environmental practices that were allowed in CRP. Through this reopened enrollment period, USDA added 2.5 million acres in Grassland CRP, almost 1.9 million acres in General CRP and 902,000 acres in Continuous CRP for 2021. This is a total of 3.4 million additional acres in 2021.

In 2022, CRP enrollment was closer to previous years’ enrollments, sitting at 22.1 million acres. However, for the 2022 program year, USDA made another change to CRP to allow producers to voluntarily terminate a CRP contract in its final year. This flexibility was granted so that land could be returned to production using working lands conservation programs to help mitigate potential global food supply challenges resulting from Russia invading Ukraine at the end of February 2022.

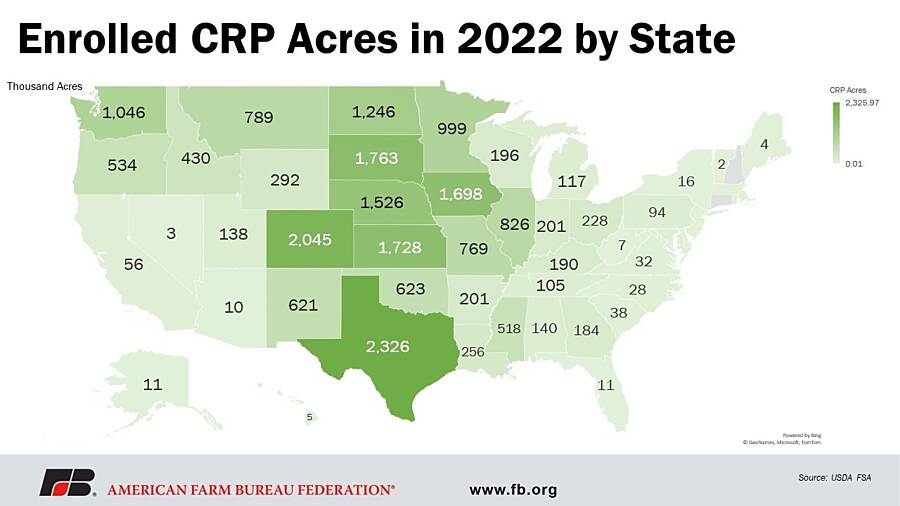

The figure below is a map of CRP enrollment for fiscal year 2022. Texas holds the largest number of acres enrolled in CRP with 2.3 million acres, followed by Colorado with just over 2 million acres enrolled in CRP. South Dakota holds the third-largest number of acres enrolled in CRP at 1.7 million acres, along with Kansas, which has a slightly lower amount of CRP acres enrolled. There are only eight states with over 1 million acres enrolled in CRP and they are largely concentrated where drought has been more prevalent recently.

CRP Rental Rates

Along with increasing the annual enrollment acreage cap, the 2018 farm bill also adjusted CRP rental rates to better align the program with market-based conditions. These provisions aimed to reduce the amount of rental payment to producers, including the per-acre costs of enrolling in CRP. The change was intended to help CRP more accurately serve its purpose of retiring more sensitive lands without competing with the local farmland market. This would prevent the government from limiting farmers' and ranchers’ access to prime farmland and keep highly productive land in production while using working lands conservation programs.

The 2018 farm bill limited CRP rental rates for general enrollment to 85% of the county average rental rate, while continuous enrollment rental rates were limited to 90% of the county average rental rate. This supports the requirement that the program account for the potential impact on the local farmland rental market of a market-based approach that would improve the availability of farmland for farmers and ranchers. The current maximum rental rate NRCS can offer for CRP is calculated in the following ways:

General CRP Rental Rate Cap: CRP rental rate < 85% of county average rental rate

Continuous CRP Rental Rate Cap: CRP rental rate < 90% of county average rental rate

It is important to note that the maximum CRP rental rates can change year-to-year since they are coupled with the NASS county average rental rate. This means that rising or declining county rental rates can impact the maximum amount of rent CRP can offer in a given contract year.

Working Lands Programs

Working lands programs were first introduced in the 2002 farm bill as a way to complement programs promoting conservation stewardship without taking away production. While CRP is a voluntary land retirement program, the other two main programs, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program and the Conservation Stewardship Program, are working lands programs that provide financial and technical assistance for implementing conservation practices to address area-specific natural resource and land management concerns on active farm or ranch working lands.

Environmental Quality Incentives Program

EQIP, through USDA, provides financial and technical assistance to agricultural producers to address natural resource concerns and deliver environmental benefits such as improved water and air quality, conserved ground and surface water, increased soil health and reduced soil erosion and sedimentation, improved or created wildlife habitat, and mitigation against drought and increasing weather volatility. It is a voluntary program with a requirement that 50% of funds go to livestock-based projects. Eligible producers enter into contracts to receive payment for implementing conservation practices. There are hundreds of approved EQIP practices, with the most widely used EQIP practices being cover cropping, nutrient management, irrigation water management, prescribed grazing, fencing and forest stand improvements. The availability and applicability of these practices vary by geography and cropping system. Approved activities are carried out according to an EQIP plan developed in conjunction with the producer that identifies the appropriate conservation practice(s) to address resource concerns on the land. Contracts last from five years up to 10 with a $450,000 payment limitation.

The 2002 farm bill removed the restriction for EQIP funds to be used to assist livestock farmers as they work to construct animal waste management facilities. Provisions in the 2002 farm bill also required NRCS to direct 60% of EQIP assistance to livestock producers. The 2018 farm bill reduced this provision from 60% to 50% and increased allocation for wildlife-related practices from 5% to 10%. Multiple amendments to EQIP focus on issues such as water quality and quantity-related practices, soil health improvement, and wildlife health improvement.

Other programs within the EQIP bucket include General EQIP, also known as state and local EQIP, which provides opportunities to address priority local or state natural resource concerns. National EQIP offers a number of initiatives, including those related to air quality, on-farm energy, organic production, high tunnel systems and landscape. Conservation Innovation Grants, the Colorado River Basin Salinity Project and Strike Force are also national EQIP initiatives.

The 2018 farm bill authorized a new stewardship contract within EQIP called the Conservation Incentive Contract, which limits the number of priority resource concerns for up to three years based on each geographic region. These contracts last for five to 10 years to incentivize the increased adoption of conservation practices. USDA is required to determine the level and extent of the practice being adopted, the cost of adoption and compensation ensuring the longevity of the practice.

Mandatory EQIP funding first set out in the 2018 farm bill increased from $1.75 billion in fiscal year 2019 to $2.025 billion by fiscal year 2023. However, the Inflation Reduction Act, which passed in August 2022, included an additional $18.05 billion for working lands programs, bringing EQIP’s total appropriation to $8.45 billion through 2026.

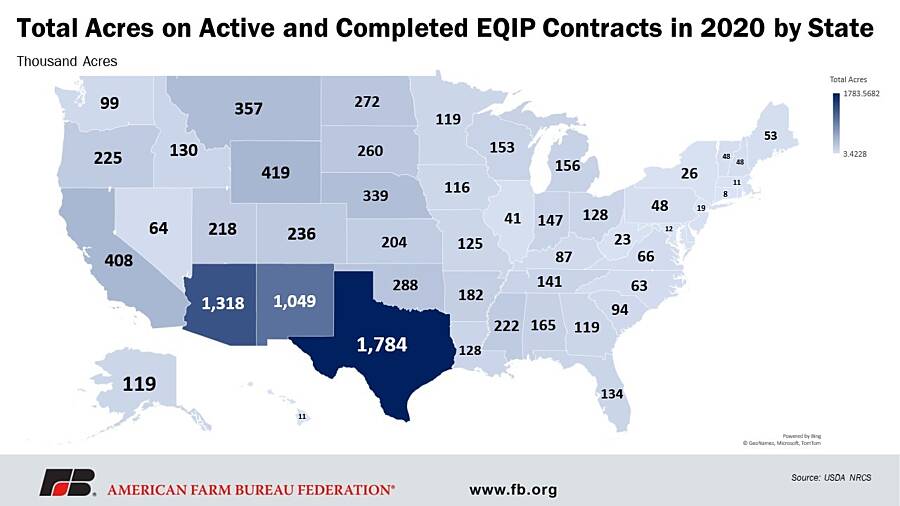

The most recent data available from NRCS indicates there were 33,701 active and completed EQIP contracts across 10.5 million acres in the U.S. in 2020. Texas has the highest amount of active and completed EQIP acres at 1.7 million acres, followed by Arizona with 1.3 million acres. New Mexico is third with just over 1 million acres enrolled in an active and completed EQIP contract for 2020. This first figure displays the total acres enrolled in active and completed EQIP in 2020.

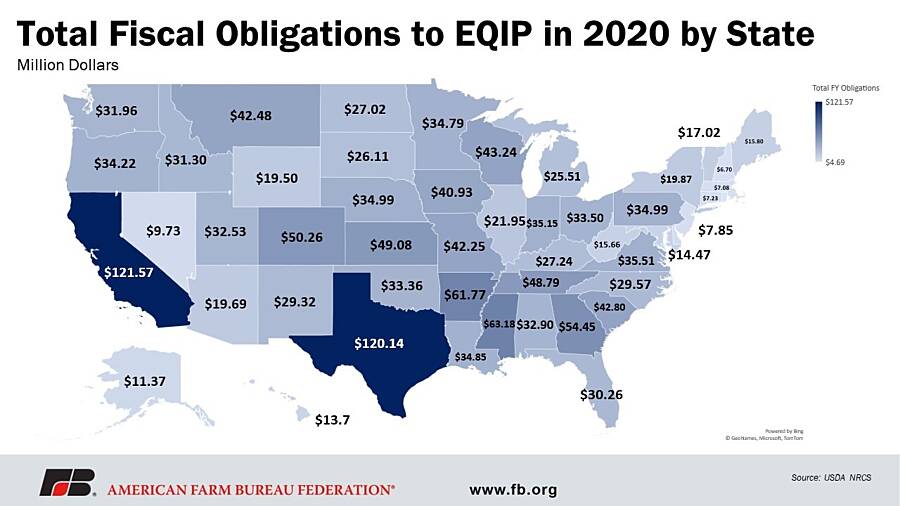

During fiscal year 2020, EQIP funding totaled $1.8 billion for financial assistance. At the state level, EQIP funding was the highest in California at $121 million, followed by Texas at $120 million. The third-highest funded state is Mississippi with just over $63 million contributing to EQIP projects. The next figure highlights total EQIP financial obligations for fiscal year 2020.

Conservation Stewardship Program

The Conservation Stewardship Program provides financial and technical assistance to support ongoing and new conservation improvements by producers who work to meet stewardship requirements on working agricultural land. In CSP, participants must meet a “stewardship threshold” for a set number of priority resource concerns when they apply for the program and must agree to meet or exceed the stewardship threshold for additional priority resource concerns by the end of the contract. In exchange, participants receive annual payments that are based, in part, on conservation performance. Contracts last up to 10 years and enrollment in the program is offered through a continuous sign-up period. Applications for CSP are accepted on a year-round basis. The program focuses on applicants’ actual and expected increase of conservation benefits, making it a unique voluntary conservation incentive that is based not just on practice, but also performance. The program is very competitive and bases selection criteria on accrued costs for similar projects. Additionally, former applicants looking to re-enroll in CSP must compete with new applications, rather than being re-enrolled automatically.

The 2018 farm bill limited CSP funding for each fiscal year, rather than limiting the number of total acres that could be enrolled in the program. Mandatory funding first set out in the 2018 farm bill for CSP was $700 million in fiscal year 2019 and increased to $1 billion in fiscal year 2023. The IRA includes an additional $3.25 billion for CSP through 2026.

NRCS data indicates there were 4,922 active CSP contracts across more than 6.4 million acres in the U.S. in 2020. New Mexico has the largest amount of acres on active CSP contracts, leading with 933,753 acres. The state with the second most acres enrolled in CSP contracts is Utah with 563,636 acres, then Oregon with 469,438 acres on active CSP contracts.

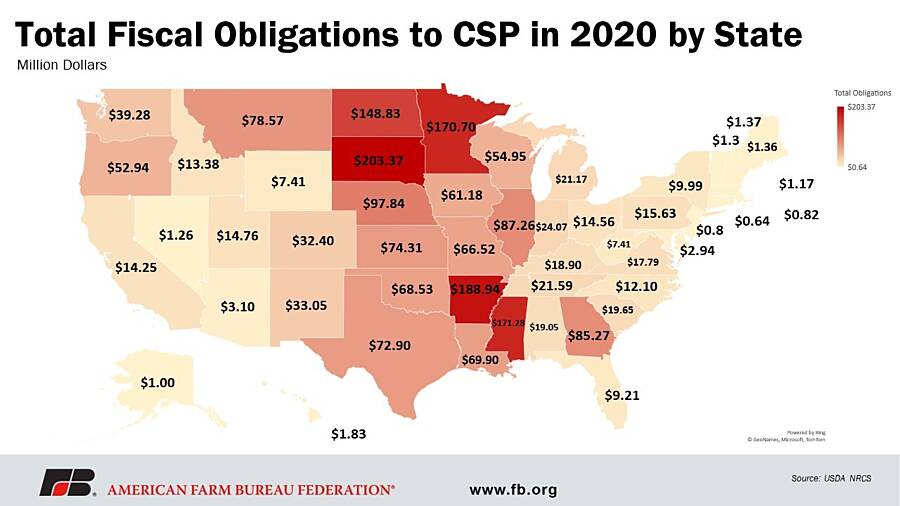

Total CSP financial obligations for fiscal year 2020 were $2.2 billion, with $306 million in technical assistance funding and $1.9 billion in financial assistance. CSP outlays in fiscal year 2020 were the highest in South Dakota at $203 million, followed by Arkansas with $188 million, then Mississippi with $171 million. The figure below highlights total CSP financial obligations for fiscal year 2020.

Summary

While conservation efforts have existed in farm policy since the very first farm bill, they became more prominent when the conservation title was created in the 1985 farm bill. The programs in Title II provide financial and technical assistance so that farmers and ranchers can proactively manage soil and water quality, improve wildlife habitat and enhance carbon sequestration efforts to boost the farm’s or ranch’s environmental sustainability without compromising its economic viability.

The conservation title has provided farmers and ranchers with voluntary, market-based incentives to adopt various conservation practices through land retirement programs like CRP and working lands programs like EQIP and CSP. While the 2018 farm bill increased enrollment limits in CRP, actual acreage enrolled has declined. The adjusted CRP rental rates implemented in the 2018 farm bill better align the program with current local farmland market conditions to prevent the government from barring farmers and ranchers from accessing prime farmland. So far, this change has encouraged farmers to install resource-conserving practices on environmentally sensitive farmland and helped keep highly productive land in production using good stewardship practices that can preserve wildlife habitat, soil and water. The working lands programs like EQIP and CSP have allowed private land to continue to be in production and have helped to provide cost-share assistance to implement conservation practices. However, the demand for these programs has consistently outpaced the amount of funding provided in the 2018 farm bill.

The Inflation Reduction Act’s $18.05 billion for working lands programs will potentially allow more producers to access these working lands program funds to implement conservation practices. Additional agriculture-specific provisions in the IRA total nearly $40 billion for spending on programs and initiatives ranging from farm bill working lands conservation and technical assistance, as mentioned in this article, to rural development and forestry. There continues to be questions about whether or not the added IRA funds contribute to added baseline dollars for the 2023 farm bill. Until those questions are answered, the current expectation is that Congress has provided more to over-subscribed working lands programs, rather than land retirement programs, with more technical assistance on voluntary incentives to help producers meet their conservation and sustainability goals.

What We're Saying

Farm Bureau Recaps Challenges and Successes of 2025

Dec 17, 2025

READ MORE

Farmers Head into 2025 with Another Farm Bill Extension, Aid

Jan 2, 2025

READ MORE

AFBF Looking for a New Farm Bill in the New Year

Jan 2, 2025

READ MORE

Farmers Urge Congress to Provide Certainty to Rural America

Dec 18, 2024

READ MORE

Top Issues

VIEW ALL