Public Lands Grazing Vital to the Rural West

photo credit: Colorado Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

Chances are, when you think of the West, images of cattle and horses and the ranchers that manage them are top of mind. For centuries, grazing livestock have been at the heart of rural economies across what is now the Western United States. Through these many generations, ranchers have contributed far more than their job titles indicate. They are county commissioners, teachers, bankers, truck drivers, energy workers, hunters, sportsmen and more – contributing directly to the stability and longevity of the communities in which they live. This article reviews the latest available economic metrics evaluating both direct and indirect benefits of livestock grazing on federally owned lands.

Background

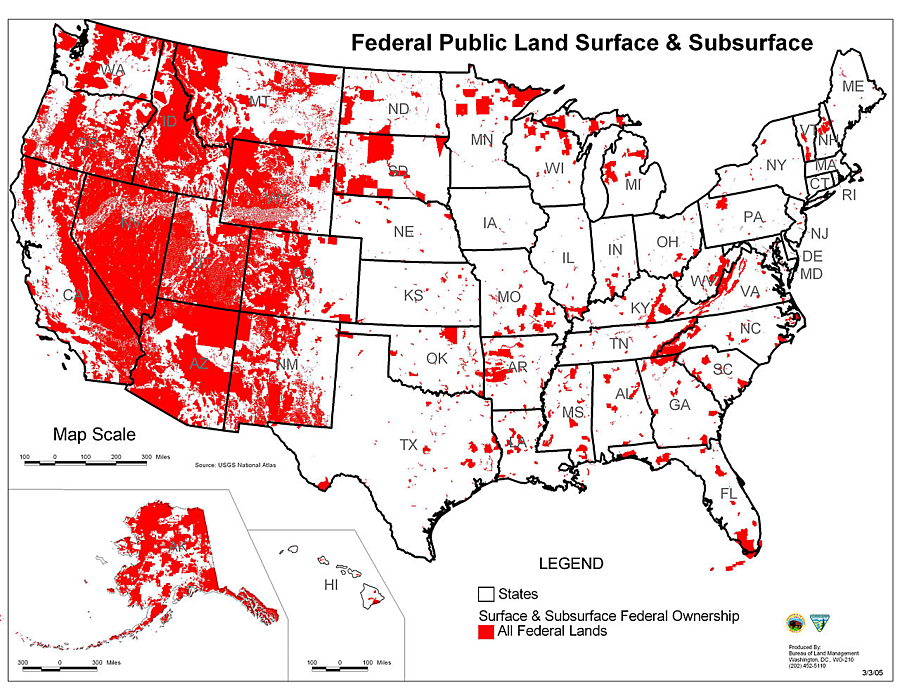

The federal government owns roughly 640 million acres of the 2.27 billion acres of land in the United States – just over 28% of total land. The percentage of federally owned land in each state varies widely, from 0.3% in Connecticut and Iowa to nearly 80% in Nevada. Federal ownership of land is heavily concentrated in the West with 61.3% of Alaska federally owned, along with 46.5% of the 11 next westernmost states. In comparison, the federal government owns 4.2% of land in the remaining 38 states. Five major federal agencies administer 620 million acres of federally owned land, led by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) at 248.3 million acres, Forest Service (FS) at 193 million acres, Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) at over 90 million acres, the National Park Service (NPS) at 80 million acres, and Department of Defense (DOD) at just over 11 million acres. Residents of heavily federally owned states that utilize lands for commerce have to abide by these federal agencies’ regulations – a challenge much of the rest of the country does not encounter.

Agencies administer permits that allow ranchers to graze livestock on specified public lands for a fee. Grazing fees through BLM, in 2023, for example, cannot fall below $1.35 per animal unit month (AUM) and any fee increase or decrease cannot exceed 25% of the previous year’s levels. An AUM is the amount of forage needed to sustain one cow and her calf or one horse, or five sheep or goats for a month. Actively permitted AUMs in 2022 ranged from a low of 254 in South Dakota to 2.1 million in Nevada, with a total of 10.8 million across the country. Active permits ranged from four in Oklahoma to 3,813 in Montana, with a national total of 17,911. Any U.S. citizen or validly licensed business can apply for a BLM grazing permit if they buy or control private property, known as a base property, that has been legally recognized as having preference for use of public lands grazing or acquire property that can serve as a base property and then apply to BLM to transfer a grazing preference from an existing property to the acquired property. There are different types of permits, the most common being the term permit, which may be issued for up to 10 years. Term permits describe the season of use, number of AUMs authorized and the kind and class of livestock that can be grazed on a specified area of federal lands. Temporary permits may be issued for a period not to exceed one year and are sparingly used. Livestock use permits are issued for a primary use other than grazing livestock for a year or less and are commonly used in research circumstances.

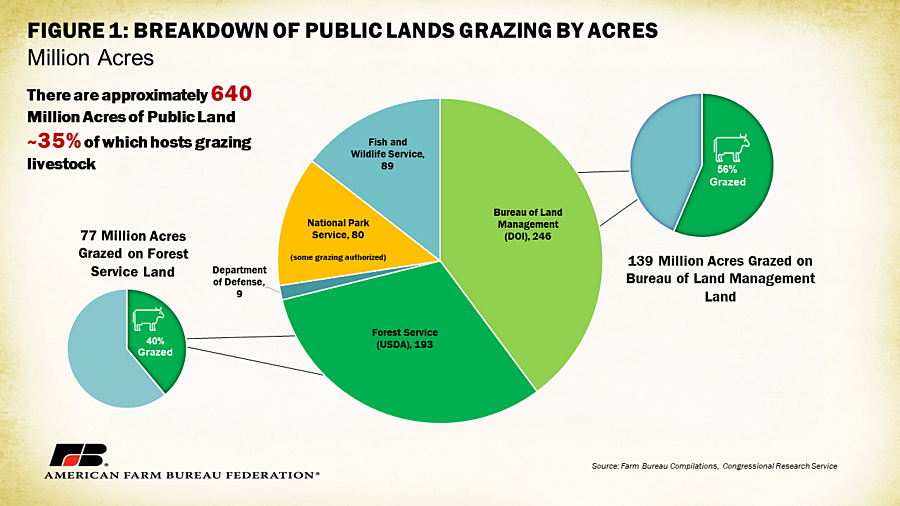

The Congressional Research Service reported that of the 248 million acres administered by the BLM, 154 million acres (62%) are available for grazing, though only 139 million acres (56%) are in use. Of the 193 million acres managed by the FS, more than 95 million acres are available for grazing (49%) and 77 million (40%) are actively grazed. There is also some grazing on NPS land, though this number is comparatively small. Of the approximately 640 million acres of federally owned land, about 35% is actively permitted for grazing purposes (Figure 1).

Direct Effects

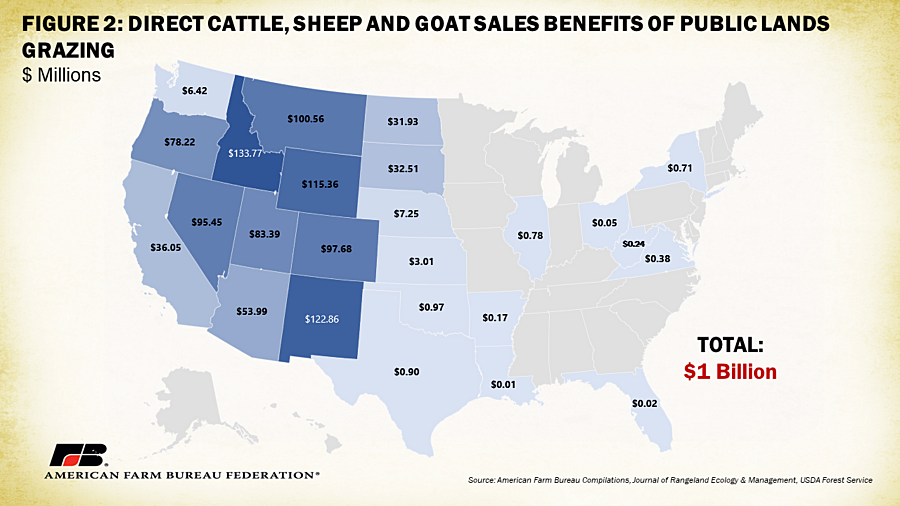

In this analysis, “direct effects” refers to the portion of monetary value of livestock sales linked to forage produced and utilized on public lands. Typically, ranching of cattle, sheep and goats uses a combination of private and public grazing lands, as well as grazed forage and purchased forage and/or grain. This means that while a finished steer that ultimately ends up at market somewhere in the Midwest may have started on public lands forage, many other sources of forage contributed to its final market weight. In a recent study by the U.S. Forest Service, researchers focused on quantifying economic contributions of federal grazing at the state and national level by adjusting sales values reported by the census of agriculture by active AUM numbers. This methodology allows us to estimate the value of end livestock sales directly attributable to public lands forage. Figure 2 displays the combined value of cattle, sheep and goat sales linked to public lands grazing. In total, over $1 billion in livestock sales value is attributable to public lands forage. States like New Mexico, Wyoming, Idaho and Montana all come in at over $100 million each. The small values calculated for some Eastern states is linked to small cattle grazing allotments under the FS. NPS grazing was not estimated.

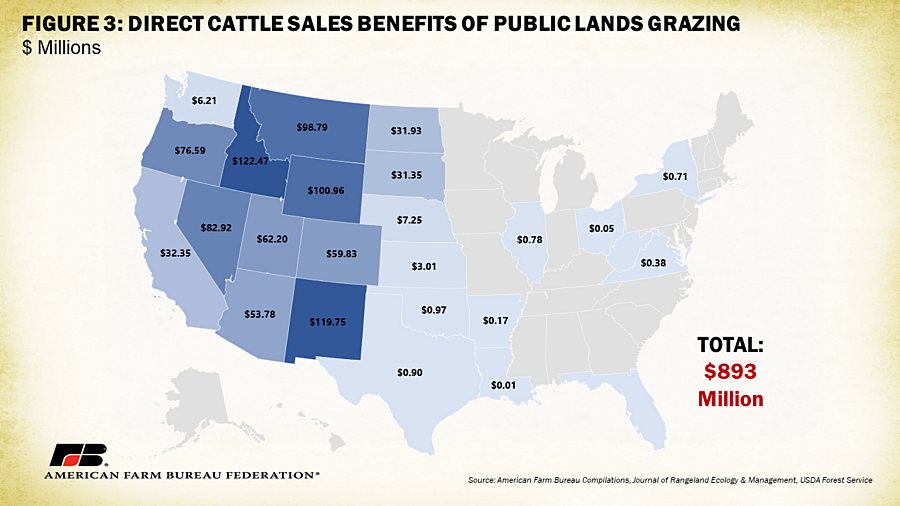

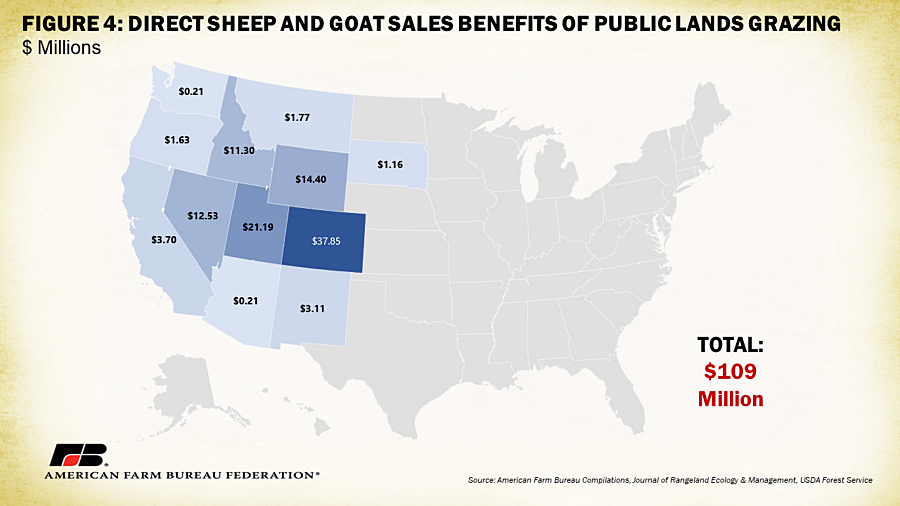

Figures 3 and 4 break down these direct estimations further. Figure 3 displays the value of cattle sales attributed to public lands forage. Close to 90% of the estimated total livestock value, or $893 million, is linked to cattle production. Idaho ($122 million), New Mexico ($119 million) and Wyoming ($100 million) are the top public lands cattle states. Figure 4 displays the value of sheep and goat sales attributed to public lands forage, with nearly $110 million in total value. Colorado leads at $38 million, followed by Utah ($21 million) and Wyoming ($14 million). These direct sales values contribute to the income basis for thousands of rural families in these states. Economic modeling specific to Idaho, Oregon and Nevada showed the loss of 5,389 active grazing permits resulted in an average 60% decline in cattle sales, 50% decline in labor income, a 65% decline in personal income (from $33,940 to $11,812), per operation, and billions in downstream economic losses. Additionally, the tax revenue received on these sales supports public safety, education and infrastructure in locations that are often already underserved and don’t otherwise receive tax revenue from federally-owned land.

Indirect Effects

There is a wide array of indirect economic effects associated with public lands grazing. Notably, ruminants like cattle, sheep and goats utilize forage on otherwise marginal lands to convert low-quality forage into high-quality nutrients humans can consume. Ranchers who can pair private land forage and purchased feed with public lands forage lower their input costs, helping make margins workable, especially during periods of high feed costs. Though the direct sales value of livestock weight gained on public lands is a little over $1 billion, the value of cattle and calves produced in the 13 westernmost states sits at over $16 billion. In 2021 alone, states with large swaths of public land like Colorado (35% federally owned), California (45% federally owned) and Idaho (62% federally owned) yielded $4.2 billion, $3.1 billion and $1.6 billion in total cattle and calf sales, respectively. Many of the cow-calf pairs and yearlings raised in these states spent some time grazing on public lands, meaning those lands contributed to the lifecycle and final marketable value of these animals. Removing the option of public lands would further pressure private lands to produce additional forage and feed, increasing input costs for producers and food costs for consumers. Not to mention, many communities reliant on grazing systems are often isolated in remote locations making them difficult to access. In many cases, federal land often crisscrosses and even divides private property into what geographically looks like abstract checkerboards of federal and private land. A decrease in the ability to feed livestock on rangeland that exists near or adjacent to a rancher’s own property often shifts demand to offsite feed resources that can be expensive and difficult to receive, potentially undermining the viability of the ranch operation.

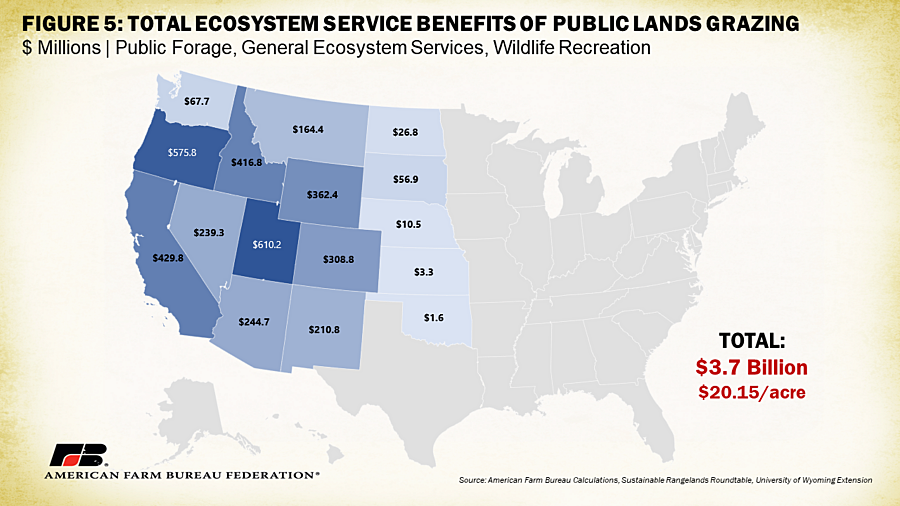

Grazing also provides indirect economic benefits by helping preserve regional ecosystems. Properly managed rangelands can increase soil organic matter, improving soil structure and contributing to increased water storage capacity and filtration, which is important for reducing the severity of drought conditions. Grazing ruminants feed off perennial forage, promoting complex roots structures that minimize soil erosion and increase carbon sequestration. They also help maintain distinctive plant communities necessary to support certain threatened and endangered species. General wildlife habitat, open space and recreation opportunities are just a few of the many other benefits retained when land is used for grazing. These benefits are often not present in alternative land uses and are difficult to replace with human-made services. In a University of Wyoming study, researchers estimated the value of some ecosystem services generated by cattle grazing on both private and public lands. Researchers identified four different types of ecosystem services: 1) provisioning, such as production of food and water; 2) regulating, such as control of climate and disease; 3) supporting, such as nutrient cycles and crop pollination; and 4) cultural, such as spiritual and recreation benefits. Though many of these services are difficult to put a monetary value on because they are not sold or traded, estimates were generated for forage production, general services (intended to capture conservation and climate-related benefits) and wildlife values (focused on wildlife preservation and recreation).

Nationally, it was estimated that federal rangelands contribute $3.7 billion in ecosystem services which translated to $20.15 per public acre grazed. For comparison, after adjusting for the approximately $26 million ranchers pay in grazing fees each year, taxpayers support appropriations for rangeland management programs at about 30 cents per acre. Excluding all other benefits of public lands grazing, consumers have a net return of $19.85 per 30 cents spent to support federal lands grazing. Figure 5 displays these state estimations. Utah and Oregon had the highest ecosystem service values at $610 million and $575 million, respectively.

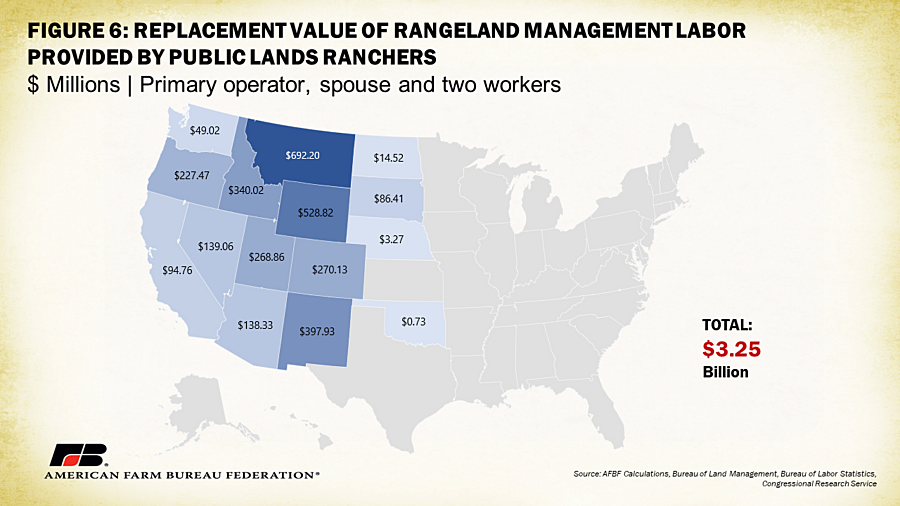

An often-overlooked benefit of public lands grazing is the land stewardship benefits offered by ranchers, their families and their employees. The federal government employs thousands of conservation scientists, foresters, rangeland management specialists, forest and conservation technicians and others tasked with helping manage and conserve land appropriately. Most ranchers do a portion of these tasks free of charge to taxpayers as part of their everyday role as rangeland operators. Median government salaries reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for these positions range from a low of $39,180 for entry-level technicians to well over $64,010 for more specialized positions. A hypothetical removal of public lands grazing would shift the burden of ground-level management of millions of acres currently shared by private ranchers and their employees to government agencies.

To grasp the extent of this cost, the replacement value of public lands permittee operators, their spouses and two hypothetical workers was calculated. At the $64,010 rate for operators and their spouses and $39,180 for each of the workers, each ranching operation would, conservatively, cost the government $206,380 to replace. Between 2002 and 2016, the number of operators with grazing permits was averaged to 15,755 operators. This means, in total, the labor replacement value of these ranching operators would be at least $3.25 billion annually. Figure 6 displays these calculations by state, with the highest replacement costs in Montana ($692 million) and Wyoming ($528 million), both very sparsely populated states where rural residents take on the brunt of rangeland management responsibilities. The families who live in rural communities are often drawn by the inherent role they play in stewarding the land, a passion that saves taxpayers billions in rangeland management duties.

Conclusion

Cattle, sheep and goat producers across the Western U.S. have partnered with federal agencies for generations to manage hundreds of millions of acres of land. As a result, consumers across the country have benefited from a more resilient and economical domestic food supply, countless ecosystem and climate-related gains of ruminant grazing and open lands preservation, and the effective and careful management of public lands. With each dollar produced by an agricultural community multiplying through downstream channels into many billions in economic value, public lands grazing is a vital part of the Western economy, and its loss could threaten the livelihoods and traditions of thousands of rural communities.

What We're Saying