Rail Order Delays, Empty Exports and Equipment Shortages – Transportation Disruptions Persist

Daniel Munch

Economist

Market access is vital to the operation of any business, including farms and ranches across the United States. The complex system of highways, rail lines, rivers and flight paths crisscrossing the nation, and ocean ports dotted along the coasts allow inputs to reach producers and goods to reach customers – when these systems function effectively and efficiently. Over the past several years, starting with the COVID-19 pandemic and exacerbated by global geopolitical rifts, supply chain fluidity has plummeted, with heavy disruptions across freight delivery. Previous Market Intels such as Congestion at West Coast Seaports Hinders Trade Boom, Increasing Freight Rail Rates Put Additional Pressure on Farm and Ranch Income, Widespread Port Congestion Threatens Farm Exports and Farmers and Ranchers Feel Crunch of Railway Supply Chain Shortfalls outlined many of the factors complicating the ability of farmers and ranchers to cost-effectively utilize rail systems and ocean ports to market their products. Today, we provide a mid-year status update on these vital transportation systems.

Total grain rail cars loaded and billed dipped slightly in the second quarter of 2022 from 381,000 cars in quarter one to 373,000 cars in quarter two. This 8,000-car difference is half the decline from quarter two 2021, a year ago, when 391,000 grain cars were loaded and billed across all carriers. In other words, railways loaded and billed fewer grain cars than last quarter and this time last year. BNSF and UP, railroads that processed 64% of all grain rail cars in quarter two 2022, shipped 9% and 14% fewer grain rail cars than the same period last year, respectively.

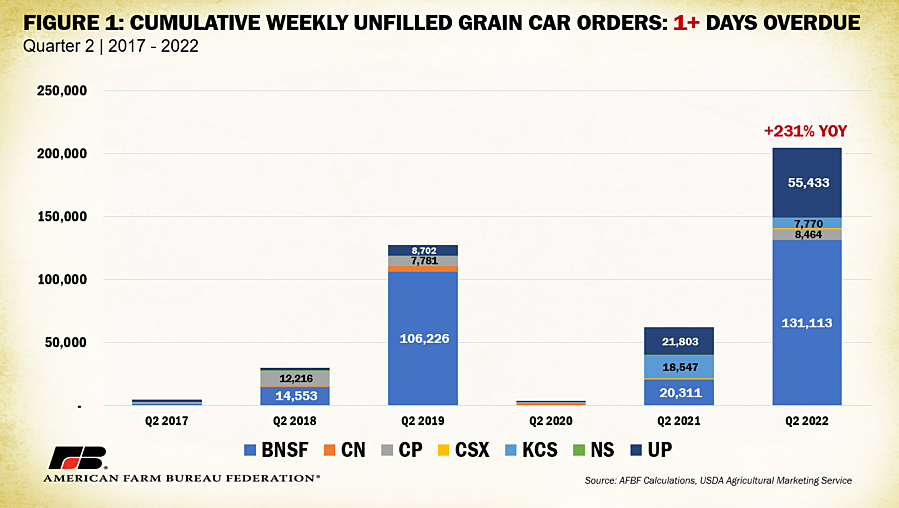

A look at cumulative weekly unfilled grain car orders, a metric that tracks grain cars not effectively loaded and billed, reveals these declines are not due to reduced demand from shippers. As a reminder, each railroad reports its definition of “unfilled order” slightly differently but generally it is the number of cars a shipper (such as a grain elevator) ordered but did not receive. For example, if a grain elevator ordered 10 cars from a railroad and received seven, that would leave three unfilled orders. Though railroad companies report the number of these unfilled orders to the Surface Transportation Board weekly, the dataset does not distinguish between rail cars still undelivered between weeks or new undelivered grain cars. This means grain cars that are still undelivered over one week are counted again in the following week’s report until successful delivery. For example, in a quarter with 130,000 cumulative weekly unfilled grain car orders it is possible that 10,000 grain cars were undelivered consecutively over the 13 week period, 130,000 different grain cars went undelivered at one point within the 13 weeks, or a combination of the two. Regardless, this unit allows for an overtime comparison of reported unfilled orders in one statistic. Figure 1 displays the cumulative number of weekly grain car orders in the second quarter from 2018 to 2022 that were one or more days overdue. Between the second quarter of 2021 and second quarter of 2022, the number of these cumulative unfilled orders jumped from 62,000 to 204,000 – a 231% increase. Year-over-year, BNSF saw a jump of over 110,000 cumulative unfilled orders (+546%) and UP saw an increase of 33,000 (+154%). Comparing quarter one, 2022 and quarter two 2022, there has been a 49% (66,000) increase in cumulative unfilled grain car orders one or more days overdue, which highlights conditions have not improved for shippers since our first quarter analysis.

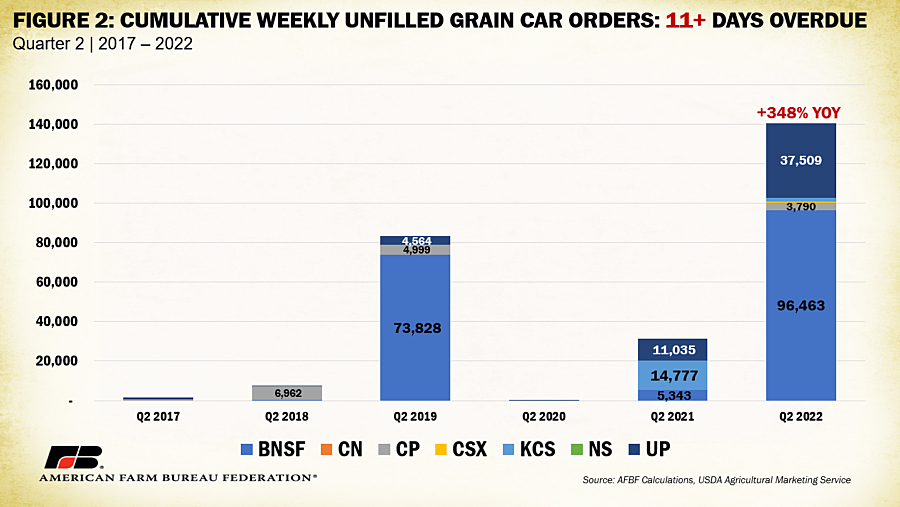

Of these 204,000 cumulative unfilled grain car orders one or more days overdue, nearly 70% or 140,000 were also 11 or more days overdue – a 348% increase from the second quarter last year and 82% increase from last quarter. Year-over-year, BNSF saw a jump of over 91,000 cumulative unfilled orders 11 or more days overdue (+1,705%) and UP saw 26,000 (+240%). Most order delays are lasting 11 days or more, putting grain mills or livestock operations reliant on a steady stream of raw materials and feed in limbo. As expected, the bulk of unfilled grain car orders have been concentrated in grain-heavy regions of the Upper Midwest and Central Plains with North Dakota, Minnesota, Nebraska and Kansas all having over 20,000 cumulative weekly unfilled orders across quarter two 2022.

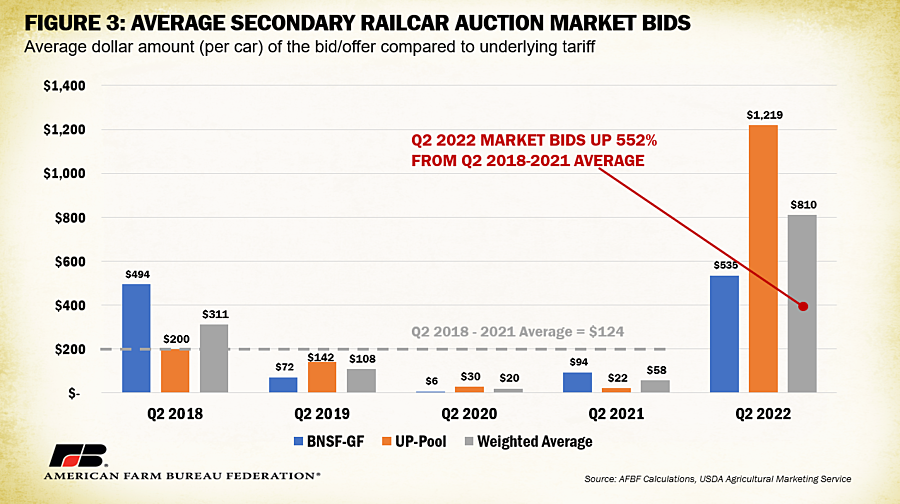

One area that further reveals the impacts of unfilled orders on shippers is the secondary rail market where shippers bid against each other for contracts that could increase the chance of getting delayed product successfully moved. Last quarter, bidders faced a near 500% increase in secondary railcar auction bids from the prior four-year average (between BNSF and UP). This quarter, bidders faced even higher auction offers – up 552% from the prior quarter two four-year average (from $124 to $801). Figure 3 displays these quarter two comparisons, highlighting the magnitude of demand that remains within secondary railcar markets. Continued inflated rates in these auctions act as proxy for railway efficiency when shippers are forced to bid for a shrinking number of successfully loaded and billed contracts, as reflected in heightened unfilled order metrics.

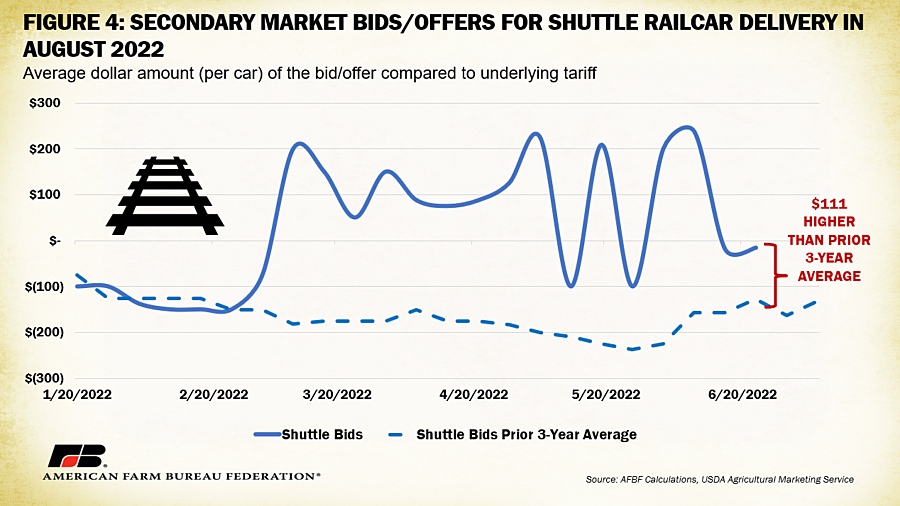

On a marginally higher note, secondary market bids for shuttle service have cooled for deliveries to be made in August from highs for deliveries made in April. Figure 4 shows for the week ending June 24 that bids/offers were $111 higher than the prior three-year average for August shuttle car deliveries and below the underlying contract tariff (as reflected in a negative value). This is a much slimmer margin than the $2,535 difference previously analyzed for April contracts – although rates remain volatile and well above average. Shippers with flexibility in moving product may participate into the secondary market to take advantage of high bids for existing contracts, further contributing to delivery uncertainty.

Considering other service quality metrics, rail speeds continue to decline, with the average speed of grain and ethanol lower than other goods. As part of their submission to the Surface Transportation Board, railroads provide data on the average speed of their trains (in miles per hour), broken out by commodity/type such as automotive, coal, crude oil, ethanol, grain, intermodal, manifest, etc. In early 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic initially dropped demand for goods, rail speeds reached 26 mph for all goods and 25 mph for grains and ethanol – with less pressure on railways, fluidity was high. More recently, the average speed for all goods has dropped to 22 mph (-14%) from quarter two 2020 and 21 mph (-15%) for ethanol and grains. With 140,000 miles of railways in the U.S., even minor drops in average rail speeds compound downstream service efficiency. Rail origin dwell times, the number of hours trains spend waiting after initial release at origin, have increased by 18% across railroads between the first quarter of 2022 and the second quarter of 2022 and 62% from quarter two last year. KCS experienced a 95% increase in origin dwell times between the first and second quarter followed by CSX which faced increases of 78%. On the terminal dwell time side, quarter-to-quarter waiting times have increased by 2% this year and 12% comparing quarter two 2022 to quarter two 2021. Rail yards with the largest quarter-to-quarter increases included Harvey, North Dakota (+91%); Conway, Pennsylvania (+88%); Glenwood, Minnesota (+85%), and Louisville, Kentucky (+72%). Slowed and delayed service contributes to increased rates of unfilled orders across the country.

Many of the reasons for service and quality disruptions discussed in previous Market Intels remain relevant. Low container and equipment inventories have stalled operational capacity across all segments of the transportation system. More recently, discussion of the availability container chassis, the trailer frames specifically designed to carry a range of container types over railways and highways, has reached center stage. Even if a surplus of containers existed, chassis are essential to transport them. Chassis are also limiting the ocean port side of the equation where turnover of chassis between customers has been slowed to a pinch point. Further, the price for a chassis has reportedly tripled, from an average of about $7,000 to over $21,000 each.

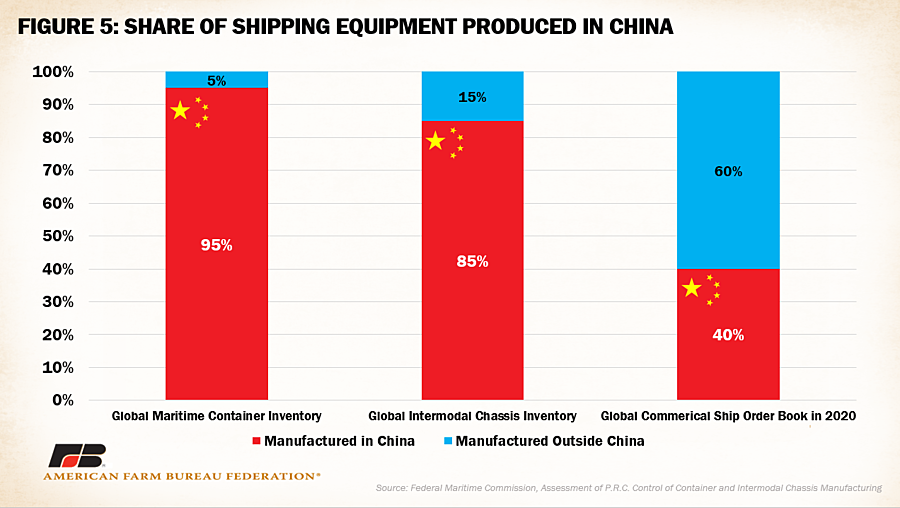

Currently, there are very few containers, container chassis and ships produced domestically, with the bulk of manufacturing taking place in China. Figure five displays the percentage of global inventory of chassis, containers and ship orders manufactured in China. According to the Federal Maritime Commission, a very small number of large Chinese firms control 95% of global maritime container inventory production, 85% of global intermodal chassis production and 40% of the global commercial ship order book. Relying on firms in a single foreign nation for production of equipment essential to the movement of goods such as food and fuel has its own national security implications in addition to general supply constraints.

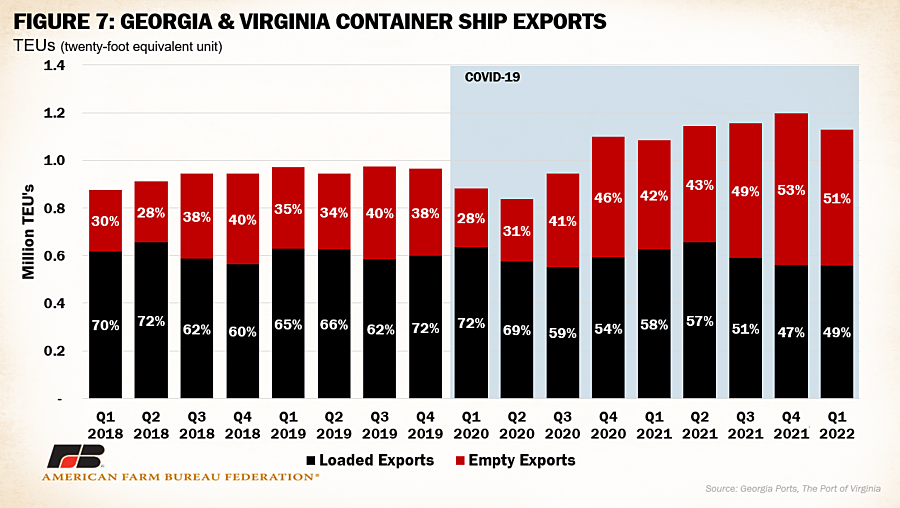

Speaking of the ocean freight network, large quantities of exports continue to move overseas without first being filled with U.S. product. Some ocean carriers consider it more efficient to ship empty containers rather than wait for export goods to be loaded, which has led to a significant decline in the number of containers available to agricultural exporters. Carriers are also incentivized to return containers abroad as soon as possible to take advantage of freight rates that remain much higher for routes from Asia to North America than North America to Asia. Figures six and seven illustrate the increased proportion of export containers that return empty from both West and East coast ports. In quarter one of 2022, 70% of exported containers from California were empty – the fifth consecutive quarter with empties over 65% of exports. At Georgia and Virginia ports, empty export containers remain at nearly 50% of export container volume – well above prior-year rates. Notably, as the volume of imports processed has increased under a period of high demand for international goods, that capacity has not been reflected in increases in loaded exports. Port operators and carriers have argued stacks of empty containers go unclaimed for extended periods of time – a possible result of compounding trucking delays.

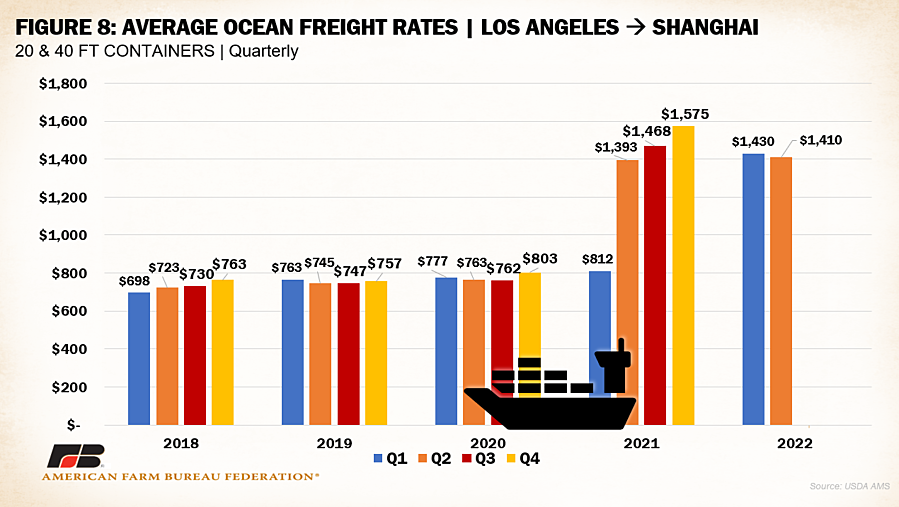

Ocean freight rates for U.S. exporters remains at heightened levels, further pressuring bottom lines for producers reliant on foreign markets for revenue. Figure 8 displays average ocean rates for 20- and 40- foot containers moving from Los Angeles to Shanghai, China. Rates hover around 75% above pre-pandemic levels with few signs of relief ahead. The compounding impact of widespread price increases for inputs like fertilizer and fuel combined with general inflationary pressures and record transportation costs continue to whittle away at margins.

Labor and crew availability continue to handicap all aspects of the economy. Uncertainty surrounding ongoing negotiations between the International Longshore Warehouse Union and Pacific Maritime Association has placed further tension on the future of port efficiency. ILWU represents more than 22,000 west coasts port workers that help move over 40% of U.S. containerized exports from California alone. PMA represents shipping lines and terminal operators at the 29 west coast ports. The prior agreement expired on July 1 and governs a wide array of employment provisions including shifts, wages, training, general welfare and pensions among others. Basic wages (without any skill level) start at $33.31 per hour and go up to $46.23 an hour with skill levels increasing pay differentials from there. As discussions continue, both sides have tentatively agreed to continue normal operations without risk of strike or lockout. Safety, wages, benefits and technology are said to be priorities under the new contract. Fragile relationships between worker unions and freight operators jeopardize an already weakened labor supply.

Conclusion

Disruptions present at each step of the supply chain intensify frustration for producers and customers alike. Both railways and ocean ports play an essential role in cost-effectively and reliably moving agricultural goods to their destination. Service disruptions, delays and heightened costs for shippers persist well into the second quarter of this year across ocean ports and railways. Legislation such as the Ocean Shipping Reform Act should assist in the much-needed movement of U.S. agricultural goods. New guidance released by the Federal Maritime Commission requires carrier invoices to report additional contract specifications related to detention and demurrage rules, applicable rates and “free time” which is the given amount of time for container pickup. This change, however, remains one small piece of a larger puzzle of possible creative solutions.

What We're Saying

Canadian Strike Would Derail Key Ag Trade Transport

Aug 21, 2024

READ MORE

NPR: Canada Faces a Massive Impending Railway Strike

Aug 21, 2024

READ MORE

What Will the Collapse of Baltimore’s Key Bridge Mean for Agriculture?

Mar 28, 2024

READ MORE

Unfilled Railroad Grain Car Orders Persist into 2023

Mar 1, 2023

READ MORE