Revised USDA Farm Income Forecast Sends Positive Signal on Farm Economy

photo credit: Arkansas Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

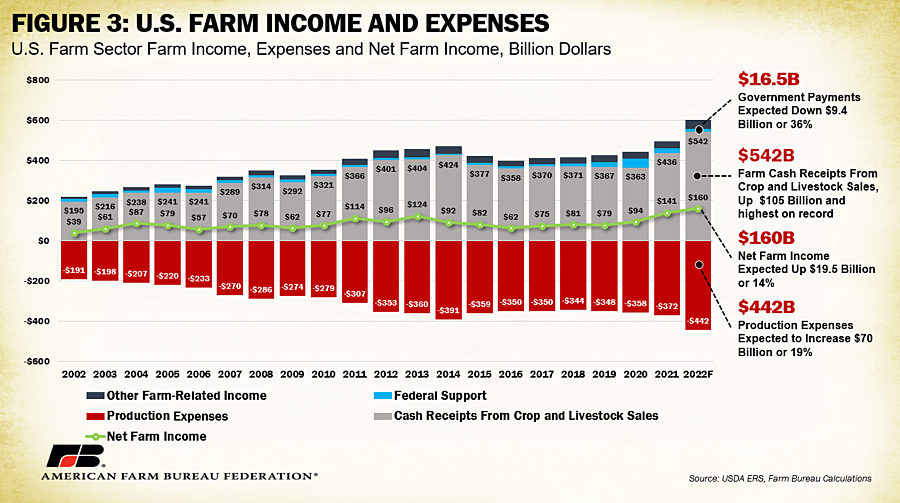

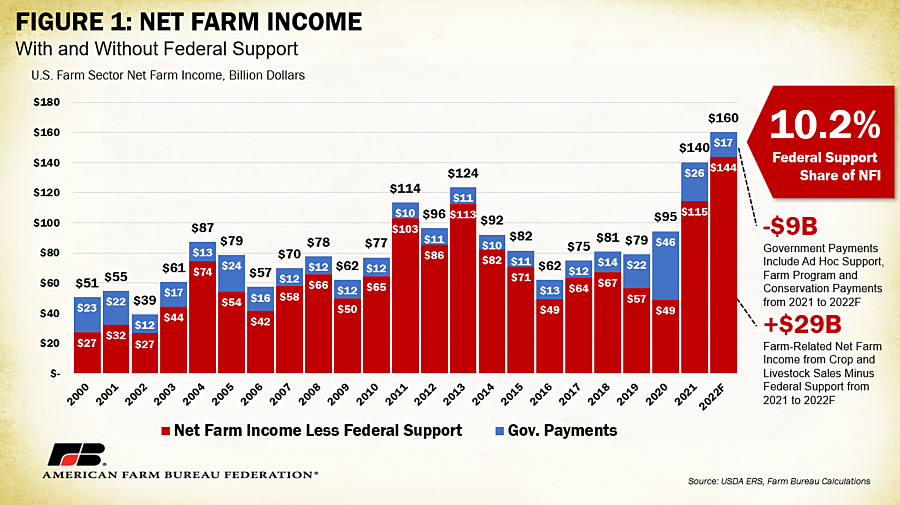

USDA’s most recent Farm Sector Income Forecast, released Dec. 1, anticipates an increase in net farm income for 2022. U.S. net farm income, a broad measure of farm profitability, is currently forecast at $160.5 billion, up 13.8%, or $19.5 billion, from 2021’s $140.4 billion. This contrasts with both USDA’s original February estimates, which forecast a $5.4 billion (-4.5%) decline in net farm income, and USDA’s September estimates, which forecast an increase of only $7.3 billion (5.3%). When adjusted for inflation, 2022 net farm income is expected to increase $10.7 billion (7.2%) from 2021 and be at the highest level since 1973. This is slightly more than 53% above the 20-year average of $104 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars. The report also finds the largest increase in production expenses on record in both numerical and percentage terms, up nearly $70 billion across the farm economy (18.8%).

It is worth noting the wide variation in individual farmer net returns in 2022. Volatile markets have meant that when a farmer chose to book their fertilizer purchases or their crop sales, for instance, could have a large impact on their bottom line. In addition, drought and natural disasters put regionally specific stress on many producers. Ever-changing federal, state and local laws including labor and conservation requirements present complex institutional risk farmers must navigate. Consideration must be given to individual and localized farm operation challenges to measure the health of the broader farm economy.

Net Farm Income Breakdown

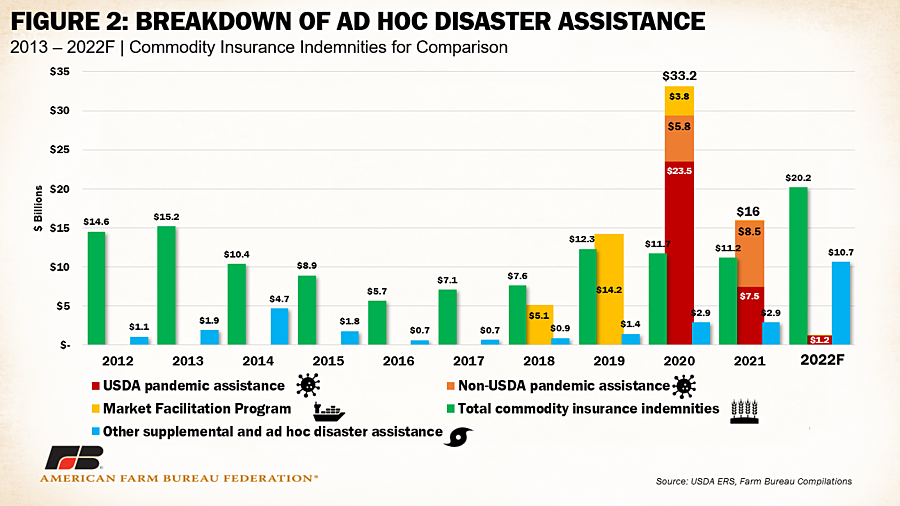

Direct government payments are forecast to decrease by $9.4 billion, or 36.3%, between 2021 and 2022. This is lower than the $12.8 billion, or 50%, drop forecast in September. As displayed in Figure 2, the decrease corresponds to reductions in both USDA pandemic assistance, which included payments from the Coronavirus Food Assistance Programs and other pandemic assistance to producers, and non-USDA pandemic assistance programs, such as funds from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program.

From 2021 to 2022, federal payments through USDA’s pandemic assistance initiatives are expected to drop $6.3 billion, from $7.5 billion to $1.2 billion, or 83%, and non-USDA pandemic assistance is expected to disappear completely, a difference of $8.47 billion from 2021. In addition to the reduced pandemic-related payments, the Market Facilitation Program, which provided a series of direct payments to farmers and ranchers impacted by trade retaliation, ended in 2021 and will not be part of net farm income going forward. The “other supplemental and ad hoc disaster assistance” category includes payments from the Wildfire and Hurricane Indemnity Program (WHIP+), Quality Loss Adjustment Program, and other farm bill designated-disaster programs. Most recently, this includes the Emergency Relief Program (ERP), which replaced WHIP+ for 2020 and 2021 disaster-related crop losses and has paid out over $7.1 billion to producers in Phase 1 as of the end of November. The activity under this program pushed payments from the ad hoc assistance category from the original February projection of $2.9 billion to $10.7 billion – a 264% increase – the primary reason for a smaller drop in government-linked payments. The recent announcement of ERP Phase 2 and the new Pandemic Assistance Revenue Program, meant to further assist producers who experienced revenue declines in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, will likely increase future federal payments to producers. In Figure 2, total commodity insurance indemnities, which are triggered in the event of revenue or yield loss for growers who have purchased crop insurance, are not direct government payments but are included for comparison. Commodity insurance indemnities are expected to increase in 2022 by 80%, or $9 billion, moving from $11.2 billion to $20.2 billion. This increase is the likely result of increased crop insurance enrollment by those who received a WHIP+ payment and who must purchase crop insurance or Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program coverage (when crop insurance is not available) for the next two available crop years under requirements – a requirement of ERP also.

Livestock

The largest portion of increase in net farm income is tied to a projected jump in cash receipts from livestock due to higher prices. The value of livestock production (in nominal dollars) is expected to increase nearly 31%, or $60.2 billion, in 2022. Chicken eggs, broilers and milk are responsible for the largest percentage increases, with cash receipts for chicken eggs projected to increase by $10 billion or 115%. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) has affected over 52 million birds in commercial flocks in the U.S. including over 43 million egg layers, pressuring supplies and pushing up prices.

Cash receipts for cattle and calves are estimated to increase by $13.9 billion or 19%. Drought conditions in the West and southern Plains have damaged pastures and led to higher costs for feed such as hay. This has resulted in many farmers marketing heifers that would typically be kept for breeding and herd replacement. Heifer slaughter is currently outpacing 2021 by 464,000 head. This has resulted in a reduction in U.S. cattle inventory that will continue for years to come. Tighter cattle supplies have pulled both cash and futures prices higher, leading to growth in cash receipts.

Crops

Higher projected commodity prices have generally projected out to higher cash receipts. Receipts for corn are expected to increase 27.6% ($19.6 billion), while soybeans are expected up 29.5% ($14.5 billion), and wheat is expected up 23.7% ($2.8 billion). These three crops account for the bulk of cash receipt increase projections. A whopping 91.6% of the increase in cash receipts is expected to be linked to higher prices versus only 6.4% linked to volume changes. Still, there is much uncertainty in the marketplace. Issues such as Mexico’s commitment to ban GMO corn for human consumption, low Mississippi River levels and weather in South America could lead to market volatility and price declines not captured in these estimates. Additionally, some of these commodity price increases are still attributable to the ongoing Ukraine-Russia conflict.

On the cost side, production expenses, including operator dwelling expenses, are forecast to increase by $69.9 billion, or 18.8%, reaching $442 billion in 2022, record-high total and record-high dollar and percentage increases in one year. This includes increases in costs like cumulative feed, which are expected to increase nearly $11.3 billion, or 17.4%, to $76.6 billion and represents the largest single expense category. Fertilizer, lime and soil conditioner costs are expected to increase $13.9 billion, or 47%, from $29.5 billion to $43.4 billion. Typically, fertilizers represent about 15% of a crop farmer’s costs and an increase of this magnitude can be crushing for some producers, even with the increases in revenue. Other increased production costs in the manufactured inputs category include pesticides, which are expected up $6.3 billion, or 35%, from $17.8 billion to $24.1 billion, and fuels and oils, expected up 47.7%, or $6.6 billion, from $13.9 billion to $20.5 billion. Farmers and ranchers are facing the same challenges as other Americans when it comes to the cost of electricity, which is expected to increase $594 million (9.3%) for producers, from nearly $6.4 billion to nearly $7 billion. Interest expenses (including operator dwellings) are forecast to increase by 41%, from $19.4 billion to $27.4 billion

Other farm income, which includes things like income from custom work, machine hire, commodity insurance indemnities and rent received by operator landlords, is estimated to increase by $9.7 billion, or 30%, from $32 billion to $42 billion in 2022. When all these factors are accounted for, the resulting expectations for net farm income become apparent, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Other Considerations

USDA’s Farm Sector Income Forecast also provides expectations of farm financial indicators that can give insight into the overall financial health of the farm economy. During 2022, U.S. farm sector debt is projected to increase $27.7 billion, or nearly 5.9%, to a record $501.8 billion in nominal terms. When adjusted for inflation, the increase changes to a 0.4% decrease in farm sector debt. Nearly 69% of farm debt is in the form of real estate debt, for the land to grow crops and raise livestock. Real estate debt is projected to increase $23.5 billion to a record-high $347.8 billion, largely due to an increase in land values across the country. Non-real estate debt, or debt for purchases of things like equipment, machinery, feed and livestock, is projected to increase only slightly to $154.1 billion. The value of assets regularly being purchased with debt is rising, which means it will continue to be important for farmers and ranchers to pay down debt and cover interest to maintain a healthy balance sheet.

Inflation, currently running at about 8% a year, is another item to consider when evaluating the increase in net farm income. Inflation is both a general increase in prices and a fall in the purchasing value of money. So, while farmers are facing growth in net income, that income does not go as far. The Federal Reserve Bank has been trying to address inflation with a series of base interest rate hikes. This has several consequences including increasing the cost of debt. Farmers will face interest rates double or triple what they were in the past few years, making borrowing operating capital more costly. This can especially impact new or beginning farmers looking to purchase farmland and equipment.

Summary

USDA released the most recent estimates for 2022 net farm income, providing a year-end estimate of the farm financial picture. For 2022, USDA anticipates an increase in net farm income, moving from $141 billion in 2021 to $160.5 billion, an increase of 13.8%. Much of the 2022 net farm income is expected to be produced by crop and livestock cash receipts, a record increase in production costs and a decrease in ad hoc government support, resulting in an overall increase of forecast net farm income. Despite the increase in net farm income, farmers and ranchers still face an uphill battle. One of the greatest concerns is the increase in operating costs, particularly in fertilizer, energy and other inputs. Growing hurdles related to credit access and the rising cost of financing farming operations create uncertainty for producers looking toward the next production year. Inflation and weather uncertainty are worrying as well. These issues will challenge the ability of farmers and ranchers to reach above break-even levels.

What We're Saying

Proposed Rail Merger Comes at Farmers’ Expense

Mar 11, 2026

READ MORE

ICYMI: Farm Bureau President Offers Solutions to Increase Demand of Homegrown Food, Fiber and Renewable Fuel

Mar 11, 2026

READ MORE

AFBF President Offers Solutions to Senate Ag Committee

Mar 11, 2026

READ MORE

AFBF President Zippy Duvall's Testimony Before Senate Agriculture Committee

Mar 10, 2026

READ MORE

Top Issues

VIEW ALL