The Other Paycheck: How Off-Farm Income Keeps Farmers Farming

Daniel Munch

Economist

When most people picture a farmer, they don’t envision someone teaching math, driving a school bus or managing a bank branch. Yet for the majority of U.S. farm households, income from these off-farm roles is what keeps the operation running. In 2023, just 23% of farm household income for farm families came from farming itself — meaning a remarkable 77% came from other sources. This Market Intel explores the essential — but often overlooked — role of off-farm income in supporting farm families, buffering against market volatility and sustaining rural livelihoods. We also examine why public policy must recognize and support this dual-reliance model to ensure the long-term viability of U.S. agriculture.

The Role of Off-Farm Income

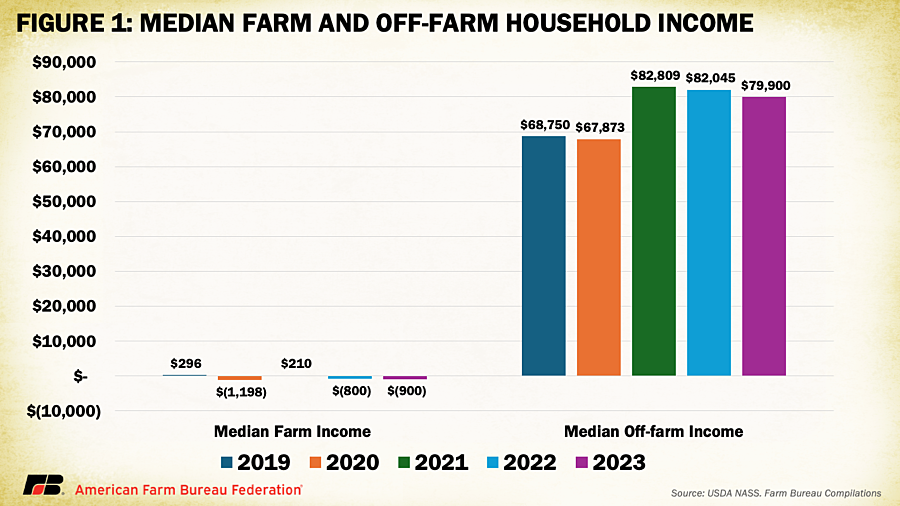

Off-farm income includes wages or salaries from non-farm jobs, investment returns and pension payments — essentially any income not directly tied to producing food, fiber or fuel. In 2023, 96% of farm households (the principal operator and their spouse) earned money from off-farm sources. At the median — the point where half of households earn more and half earn less — farm-related income was a loss of $900. Over the past five years (2019–2023), median farm income has never exceeded just $296. In sharp contrast, median off-farm income was $79,900. Off-farm income peaked in 2021 at over $82,800 and has since declined only slightly.

This stark gap is partly due to USDA’s broad definition of a farm, which includes any operation with more than $1,000 in ag product sales — a threshold that encompasses many very small-scale or lifestyle farms not intended to provide primary income. Still, the difference highlights the vital role off-farm income plays in keeping many farm households financially afloat.

Off-farm income isn’t all earned on the clock — though most of it is. Broadly speaking, off-farm income falls into two categories: earned income, which requires work or time, and unearned income, which comes from passive sources or public transfers. The majority — about 72% of off-farm income in recent years — has come from earned sources, including wages and salaries (61%) and nonfarm business income (11%). The remaining 28% has come from “unearned” sources like Social Security, veterans’ benefits, pensions, dividends and interest. These passive income streams, while smaller overall, can still play a stabilizing role — especially for older retired or semi-retired farmers no longer relying on wages.

Who’s Earning Off-Farm Income

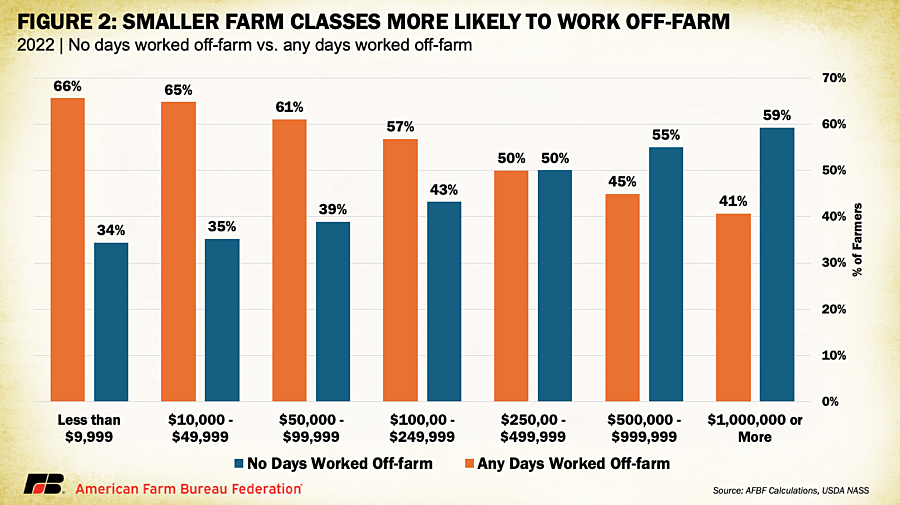

The smaller the farm—measured by gross cash farm income which includes agricultural sales and government payments—the more dependent it tends to be on off-farm employment. Among farms with less than $100,000 in annual gross sales, over 60% of principal operators worked at least one day off the farm. In contrast, that figure drops to 45% or less for farms with over $500,000 in gross sales. This pattern makes intuitive sense: smaller farms often don’t generate enough revenue to cover basic household expenses, let alone reinvest in the business. Off-farm jobs become essential to bridge the gap—helping pay for housing, healthcare, education and retirement.

On the flip side, larger farms typically require full-time attention and labor from operators, making off-farm work less feasible. Still, across all farm sizes, a notable share of producers rely on income from beyond the farm gate. This diversification helps stabilize household finances—especially in years when farm income dips into the red.

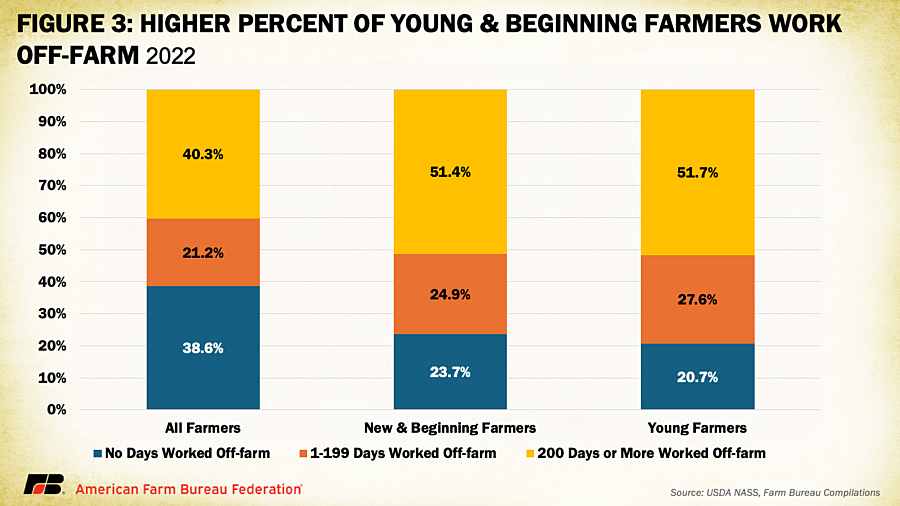

Just as smaller farms are more reliant on off-farm income, so too are young and beginning farmers. Defined as individuals 35 years or younger, or those with fewer than 10 years of farming experience, respectively, these groups are more likely to hold off-farm jobs. In fact, only about 20% of young farmers and 24% of beginning farmers reported working exclusively on the farm — compared to nearly 40% of all farmers.

This trend reflects the steep financial climb facing new entrants to agriculture. Without inherited land, equipment or equity, it’s difficult to rely solely on early farm earnings. Off-farm jobs help cover startup costs and personal expenses and provide access to health insurance and other benefits. Just as importantly, these roles offer opportunities to build credit, acquire valuable skills and develop professional networks that can support long-term success in farming.

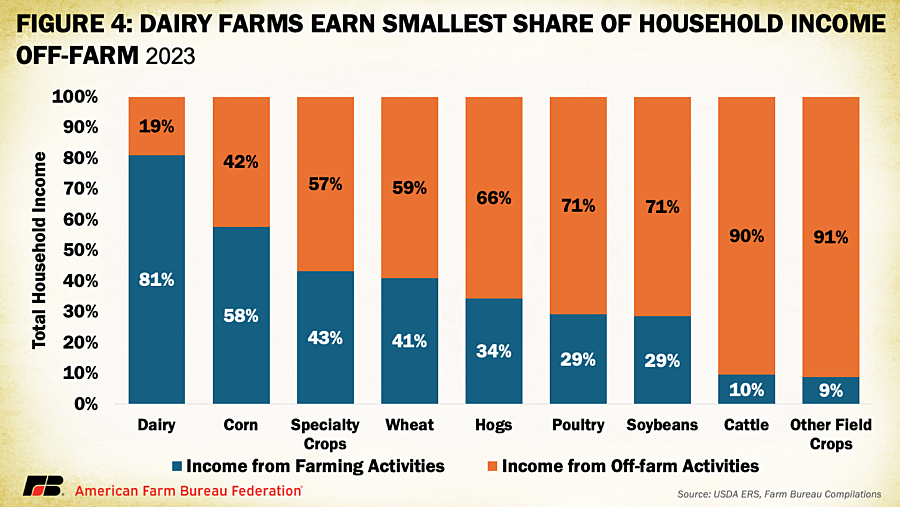

Off-farm income trends also differ widely by farm type, reflecting varying labor demands, availability of automation, production schedules and income volatility across commodities. Dairy farm households are the most reliant on income earned from the farm itself — with 81% of their household income in 2023 coming from farming activities. That’s a stark contrast to other specializations: for corn farmers, 58% of income came from on-farm sources, while cattle producers reported only 10%, and other field crop operations just 9%.

These differences are largely driven by the structure of the production systems. Dairy operations require year-round, labor-intensive management — multiple milkings a day, every day — leaving little room for off-farm employment. By contrast, row crop operations are highly mechanized and seasonal, concentrated around planting and harvest windows. This allows for greater flexibility to pursue off-farm work during the rest of the year. Cattle operations, especially cow-calf or backgrounding systems, may involve smaller daily time commitments, enabling operators to more easily maintain off-farm jobs. Additionally, because many operations with cattle are diversified or part-time, the average reflects more households that rely heavily on off-farm income.

Off-Farm Work is Strategic and Necessary

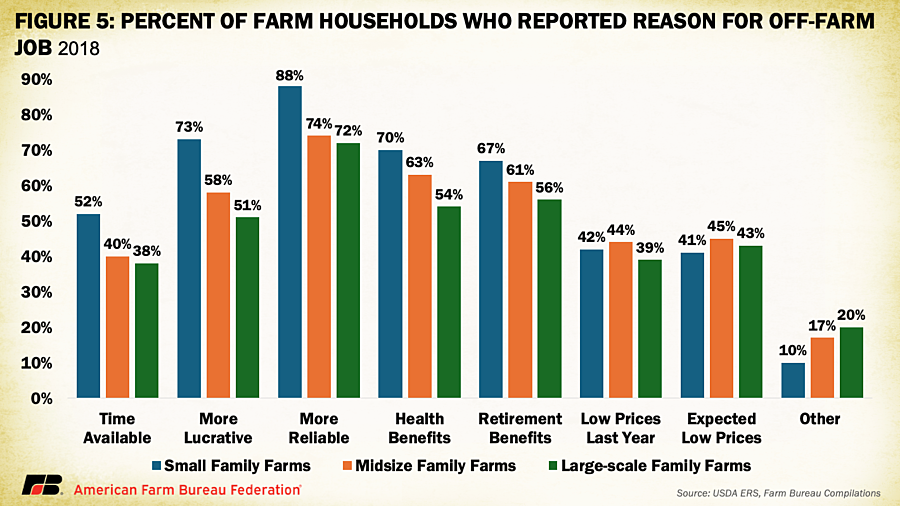

While structural and economic factors clearly drive many farm households toward off-farm income, survey data provides deeper insight into why they make that choice. According to USDA’s 2018 Agricultural Resource Management Survey, the most common reasons cited for off-farm work — across farms of all sizes — were more reliable income, higher pay than farming, and access to key non-wage benefits like health insurance and retirement plans — sometimes through public sector jobs, including positions with USDA. These motivations speak to both the unpredictability of farm income and the need for household stability.

Unsurprisingly, these reasons were cited less often by households operating larger farms, which are more likely to generate sufficient income from agricultural activities alone. Still, about 40% of principal operators or their spouses who worked off the farm pointed to specific financial pressures, such as low commodity prices or declining farm revenue, as a major influence on their decision. Interestingly, while access to health benefits was a strong incentive for many, principal operators on both large-scale and small farms where farming is the main occupation were less likely to cite it — perhaps reflecting a dynamic where one spouse’s off-farm job already provides coverage for the family.

In the end, off-farm work isn’t just a financial safety net — it’s a deliberate strategy many farm families use to manage risk, reduce stress and secure their long-term future in agriculture.

The Growing Distance Between Home and Work

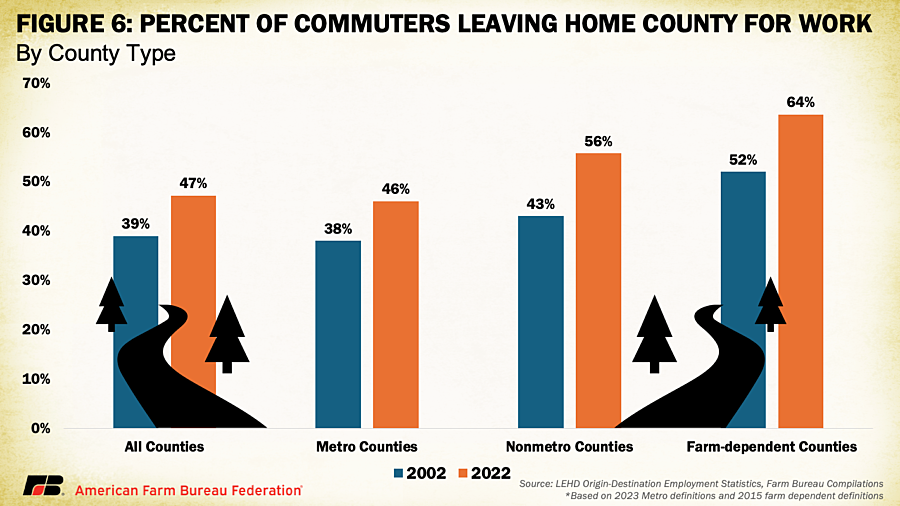

The reliance on off-farm income also reflects broader demographic and geographic shifts in rural America. As the population has become more urbanized — falling from 57% living in nonmetro areas in 1940 to just 13.7% in 2020—rural residents, including farm families, are increasingly required to commute outside their home counties for off-farm work opportunities. Between 2002 and 2022, the share of commuters leaving their county for employment rose more than 10 percentage points in both nonmetro and farm-dependent counties, with 64% of farm-dependent county residents commuting out—higher than both nonmetro (56%) and metro counties (46%).

For many farm households, this trend reflects the reality that off-farm jobs aren’t always found just down the road. As service-sector jobs like healthcare, education and retail have replaced more localized ag or manufacturing roles, farm families often travel greater distances to access the stable income and benefits those jobs offer. This growing rural-urban interdependence is a key part of the off-farm income story — and one that underscores why farm household well-being must be viewed within the context of regional labor markets, not just on-farm productivity. In today’s economy, the ability to farm often depends on the ability to commute.

Farming in a Riskier World

So what does all this mean for how we think about supporting U.S. agriculture?

The health of the farm economy is often measured by indicators like net farm income or financial ratios. While extremely valuable, these metrics overlook the broader health of rural communities — where the decline in working-age population, school closures and reduced access to goods and services can undermine the stability farmers need to stay in business. These local institutions not only serve families but often enable the off-farm income that makes farming financially viable.

Technological innovation has undoubtedly made U.S. agriculture more productive and efficient, enhancing food security and lowering costs. These advances have also reduced the amount of hands-on labor required and allowed farms of all sizes to adopt tools that improve yields and streamline operations. At the same time, as production has become more efficient and standardized — and as commodities move quickly through global markets — there’s often less opportunity to differentiate what one farm produces from another. This often leaves price as the primary factor driving a buyer’s decision to purchase an agricultural product. With tighter margins and fewer ways to stand out, financial risk grows. In this environment, off-farm income serves as a form of diversification — helping farm families spread risk beyond the commodity markets and offering the financial stability needed to continue farming in a system where volatility is the norm.

Without access to reliable off-farm jobs — which increasingly require commuting beyond one’s own county — many farm households can struggle to stay afloat. And even large-scale operations rely on vibrant communities for schools, clinics, and essential services that support family life. In the end, supporting agriculture isn’t just about what happens on the farm — it’s about the broader environment that makes farming possible.