What Happens When a Farm Bill Dies?

TOPICS

Farm Bill

Roger Cryan

Chief Economist

Washington, D.C., September 30, 2024

The 2018 farm bill will die tonight.

It could be revived later this year (or early next year) with another extension, but its time has come.

In some ways, this farm bill has been dying for several years: thanks to unanticipated price inflation in recent years, the dollar is only worth 80% of what it was in 2018. The fixed reference prices from that farm bill, which define the help from USDA that farmers depend on in tough times, are only worth 80% of what they were in 2018. The value of dollars set aside for research and innovation grants and for certain conservation programs are only worth 80% of what they were in 2018.

In addition, a lot of the funding for other climate-focused conservation programs is being spent for the last time, rather than entering the farm bill baseline accounting so that it can become available for the next farm bill.

But we have shared before what farmers and the rest of us will miss without a new farm bill.

What will we miss with no farm bill?

Death at Midnight

The death at midnight begins a calendar of expirations, let downs and price support on steroids.

Some programs will be shut down immediately, as their day-to-day authority depends on the farm bill. Among those are:

- Numerous international programs, including the Market Access and Foreign Market Development Cooperator trade promotion programs and Food for Progress;

- The Biobased Markets Program and Bioenergy Program for Advanced Biofuels;

- Several important animal health programs;

- Programs for socially disadvantaged, veteran, young and beginning farmers;

- The Specialty Crops Block Grants program; and

- The National Organic Certification Cost-Share program.

Conservation Stops… and Goes

New enrollment in some conservation programs will stop at midnight; and some could continue for seven more years. Technical assistance and several emergency conservation and restoration programs are permanently authorized.

The Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act added nearly $18 billion in funding for farm bill conservation programs – outside the farm bill and only for certain programs deemed “climate-related” by the law’s authors. These programs are all at least partially funded with supplemental funding that doesn’t have to be spent until fiscal year 2031, including the Conservation Stewardship Program (other than the Grassland Conservation Incentive), the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP, other than livestock projects), the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program.

New enrollments for most of the rest of USDA’s conservation programs, however, end tonight, including the bedrock Conservation Reserve Program, livestock projects under the EQIP program, the Grassland Conservation Incentive, and several wetland, forest and watershed restoration programs.

Permanent Law

A number of current farm bill programs operate under permanent law, meaning law without a sunset date. The most important of these are crop insurance programs and the primary nutrition programs – the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and The Emergency Food Assistance Program . Happily, these will continue to operate, although without the potential improvements and updates that would happen in a new farm bill. They both also adjust automatically to changes in price levels each year – and the crop insurance program has avenues for expansion to new agricultural products and new tools – so that they don’t need as much updating as the rest of the farm bill.

Several disaster programs are also permanently authorized, including the Livestock Indemnity Program; Livestock Forage Disaster Program; Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honey Bee, and Farm-Raised Fish Program; and Tree Assistance Program.

When people talk about permanent law and the end of a farm bill, however, they are usually talking about farm programs dating back to the 1940s and 1930s that are still on the books, but which are suspended in each farm bill. Various farm bill commodity support programs will be extended through the current crop year, but over time they will be replaced with permanent law.

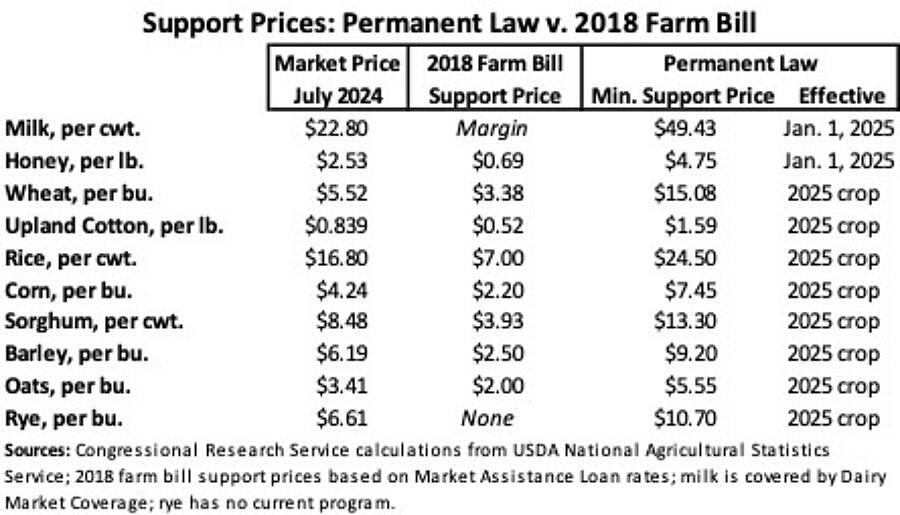

Congress has left these laws on the books as a guarantee that it will take some action to prevent the return of these old programs. The programs would support certain farm prices that are (good news) far above the current support prices and (bad news) so far above market prices that they would be very disruptive to the agricultural economy and costly to the government. These support prices are based on prices in 1910 to 1914, with adjustments for rising input costs but not for (vastly) improved yields and input efficiencies. These “parity prices” are still published every month by USDA.

For the field crops that are eligible (wheat, cotton, rice, corn, sorghum, barley, oats and rye) this wouldn’t kick in until the 2025 crop is harvested.

The Farm Bill’s Dairy Cliff: Milk and Honey

What could kick in soon – on January 1 – are price support purchases of milk and honey. The all-milk price in July 2024 was $22.80 per hundredweight. The parity price of milk is $65.90 and permanent law says that USDA should support July milk at 75% of parity, or $49.43 per hundredweight. This was historically translated into cheese, butter and nonfat dry milk purchases: the equivalent cheese price would be about $6 per pound, compared to recent prices below $2.25 per pound.

The July market price of honey was $2.53 per pound; the support price under permanent law would be $4.75.

The last time the farm bill expired for more than a couple months, USDA slow-walked rulemaking to implement these purchases and a new farm bill was in place before a pound of milk or honey was purchased; but USDA has the know-how and the facilities to begin these purchases by January 2nd, if they are so inclined. Purchasing cheese, butter and nonfat dry milk at multiples of the market price would be severely disruptive to markets, would badly distort pricing under the federal milk marketing order system and would undermine demand at home and abroad in return for very uneven benefits to farmers over a limited time. And the release of USDA stocks when permanent law is suspended again would depress markets for months.

On the other hand, it would send a strong message to Congress that action is needed.

Corn at $7.45, Wheat at $15.08; But No Safety Net for Soy

If there was no new farm bill or extension through next year, USDA would pay excessive prices under these old programs for certain crops harvested in 2025 through purchases and nonrecourse loans. The table below shows the support prices for all the crops supported under permanent law. Every other commodity loses its support programs: no program for soybeans, peanuts, sunflower seeds, canola or several other crops.

Once again, permanent law would mean a heavy cost to the government for uneven and likely temporary benefits to farmers; the high support prices would drive up prices for food, fiber and fuel, at home and abroad; and the release of stocks if and when permanent law was suspended again would flood the market.

CCC Authority

The Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) has historically been used as the secretary of Agriculture’s Swiss Army knife (regardless of political party). The farm bill directs numerous programs to draw funding from the CCC and many of those will expire tonight and in the coming months, including the commodity price and margin support programs.

The secretary’s broad ad hocauthority to support farm prices, farm income, agricultural marketing, exports, domestic consumption and conservation programs, and to provide emergency relief remains, however. And when the Department of the Treasury pays the Agriculture Secretary’s bills this fall, he has a $30 billion line of credit to work with.

This gives the secretary flexibility to operate farm income support and disaster programs to supplement action not taken by Congress. This is in line with his recent suggestions that he can use CCC authority to fill the funding gap in various farm proposals, and a point of contention among some in Congress.

Conclusion

The 2018 farm bill was a good law for its time, but that time is past.

And that farmers are calling for a new farm bill, and not an extension, is telling.

Farmers face many difficulties this year and next, from crashing crop prices to backed up transportation systems to this weekend’s devastating hurricane. All of these demonstrate how much farmers can suffer from a lack of the certainty and support that a new farm bill can provide.

It’s not too late to imagine a new five-year farm bill coming out of this Congress. It is not that hard, unfortunately, to imagine the price of inaction.

The author gratefully acknowledges Jim Monke, Randy Alison Aussenberg and Megan Stubbs at the Congressional Research Service. Their overview of farm bill expiration and permanent law was a key foundation for the above discussion. See our Market Intel reports for more discussion and analysis of farm policy and agricultural markets.